Desert locusts are harmless, solitary creatures until they get a certain chemical - and it isn't firewater, catnip or anything that comes from Colombia. It's serotonin, a common brain chemical, but in the right amount they turn into hordes of hungry ... well ... locusts.

With desert locusts, the expression of this swarming characteristic generally means serious trouble for nearby farmer. Locusts are known to sometimes swarm by the billions, and they often devastate crop yields. Dr. Stephen Rogers from the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford in the UK says about 20 percent of the world is affected by desert locusts.

"It's really interesting," says Malcolm Burrows from the University of Cambridge. "Here we have a solitary and lonely creature, the desert locust. But just give them a little serotonin, and they go and join a gang!"

Serotonin in nervous systems of locusts. Credit: Image copyright Steve Rogers

Locust Facts:

- Locusts are grasshoppers that swarm. Of the 8,000 known species of grasshoppers throughout the world only about 12 are swarm-forming locusts.

- An adult Desert Locust is 2-2.5 inches long and weighs 0.05-0.07 oz.

- A Desert Locust adult can consume roughly its own weight in fresh food per day.

- They are prodigious fliers, covering 60 miles in 5-8 hours.

- The two phases are so different in appearance and behavior that they were thought to be separate species until 1921.

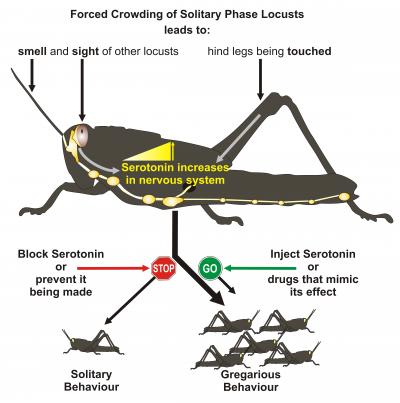

Although researchers had previously identified the sensory stimuli that trigger swarming behavior in locusts, this new finding reveals a neurochemical mechanism linking interactions among individuals to large-scale changes in population structure and the beginning of mass migration.

Although the discovery does not provide an immediate pest control solution, Paul Anthony Stevenson writes in a Perspective that these new insights "harbor considerable potential" for dealing with these harmful insects, if scientists can find viable ways to chemically convert swarming locusts back to their solitary phase.

Michael Anstey from the University of Oxford and colleagues including Swidbert Ott from the University of Cambridge and Rogers monitored the levels of serotonin in desert locusts while they triggered both solitary and gregarious behavior in the creatures. Their results show that locusts behaving the most gregariously (in swarm-mode) had approximately three times more serotonin in their systems than the calm, solitary locusts. This raises the prospect that individual neurons that drive this swarming behavior could be identified and targeted.

This kind of "switch" in desert locusts represents an extreme example of phenotypic plasticity, in which the expression of multiple observable characteristics can be generated from a single genetic characteristic. This plasticity, or adaptability, of desert locusts is evolutionarily important, and could help the insects prepare for increased competition for resources or signal necessary dispersal and migration cues.

Dwindling food sources seem to be one of those cues. Dr. Rogers says, "As their desert environment dries up, they look for food, which eventually brings them all closer together. They are looking for anything to eat, and when they run out of options, a swarm is basically inevitable."

Physically, desert locusts can be stimulated into swarming, gregarious behavior by either stimulation of the hind legs as they crawl over and jostle each other or by the combined sight and smell of other locusts. After enough of this "crowding," the locusts stop trying to avoid each other and begin coming together in a swarm.

Once Anstey and the team of researchers observed elevated levels of serotonin in swarming desert locusts, they tested whether or not both of these physical sensory pathways to swarming caused an influx of serotonin, and found that they both did. They also demonstrated that serotonin-inhibiting agents could allow locusts to remain calm and solitary despite the physical stimulation of crowding. On the other hand, injecting serotonin promoters into the locusts could induce swarming behavior even without that physical stimulation.

Serotonin is present in every multi-cellular organism on the planet, and serotonin receptors are often targeted by antidepressant drugs in humans to increase its availability. Dr. Ott says that, "many of the chemical agents that we used in this study to manipulate serotonin were at one time or another tested or used in clinical applications, such as the treatment of depression."

Comments