Chew your food well is ancient wisdom. In the past, the belief was perhaps because there was less food anyway. Chewing it longer gave the brain and stomach time to catch up with each other. Many people have reported 'their eyes are bigger than their stomach' and feeling hungry until they were very full. Others said it made digestion easier.

One thing is certain. You don't find obese people eating slowly so slow eating and thorough chewing became linked to less weight gain. The chewing process reportedly enhances the energy expenditure associated with the metabolism of food and increases intestinal motility—all summing up to an increased heat generation in the body after food intake, known as diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT). It may also mean that other types of chewing can have a similar effect, like gums.

What is lacking is a mechanism for how prolonged chewing induces DIT.

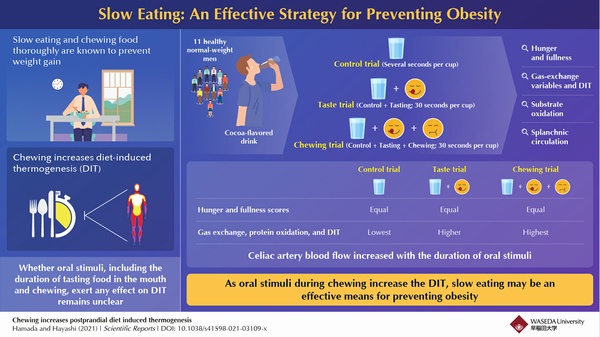

The new paper establishes a causal link by controlling for the size of the food bolus that entered the digestive tract and oral stimuli generated during prolonged chewing. The researchers excluded the effect of the food bolus by involving liquid food. The entire study included three trials conducted on different days. In the control trial, they asked the volunteers to swallow 20-mL liquid test food normally every 30 seconds. In the second trial, the volunteers kept the same test food in their mouth for 30 seconds without chewing, thereby allowing prolonged tasting before swallowing. Lastly, in the third trial they studied the effect of both chewing and tasting; the volunteers chewed the 20-mL test food for 30 seconds at a frequency of once per second and then swallowed it. The variables such as hunger and fullness, gas-exchange variables, DIT, and splanchnic circulation were duly measured before and after the test-drink consumption.

There was no difference in hunger and fullness scores among the trials. However, as Professor Naoyuki Hayashi from Waseda University describes, “We found DIT or energy production increased after consuming a meal, and it increased with the duration of each taste stimulation and the duration of chewing. This means irrespective of the influence of the food bolus, oral stimuli, corresponding to the duration of tasting food in the mouth and the duration of chewing, increased DIT.”

Gas exchange and protein oxidation too increased with the duration of taste stimulation and chewing, and so did blood flow in the splanchnic celiac artery. As this artery supplies blood to the digestive organs, the motility of the upper gastrointestinal tract also increased responding to oral stimuli during chewing.

The study highlighted that chewing well, by increasing energy expenditure, can indeed help prevent obesity and metabolic syndrome. What this means for other types of oral stimuli generated during prolonged chewing and their impact on appetite suppression merit further study.

Comments