Lacking any way to know in the past, the assumption was that the interior of the Moon had been largely depleted of water and other volatile compounds. In 2008 researchers detected trace amounts of water in some of the volcanic glass beads brought back to Earth from the Apollo 15 and 17 missions to the Moon. In 2011, further study of tiny crystalline formations within those beads revealed that they actually contain similar amounts of water as some basalts on Earth. That suggests that the Moon’s mantle — parts of it, at least — contain as much water as Earth’s. Not a lot, there is no secret world under the surface where "Game of Thrones" is actually happening, but some.

Credit: Olga Prilipko Huber

How to detect water under the surface of a moon

To detect the water content of lunar volcanic deposits, scientists use orbital spectrometers to measure the light that bounces off a planetary surface. By looking at which wavelengths of light are absorbed or reflected by the surface, scientists can get an idea of which minerals and other compounds are present.

The problem is that the lunar surface heats up over the course of a day, especially at the latitudes where these pyroclastic deposits are located. That means that in addition to the light reflected from the surface, the spectrometer also ends up measuring heat. That thermally emitted radiation happens at the same wavelengths that we need to use to look for water so they first need to account for and remove the thermally emitted component.

To do that, the team used laboratory-based measurements of samples returned from the Apollo missions, combined with a detailed temperature profile of the areas of interest on the Moon’s surface. Using the new thermal correction, the researchers looked at data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, an imaging spectrometer that flew aboard India’s Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter. The researchers found evidence of water in nearly all of the large pyroclastic deposits that had been previously mapped across the Moon’s surface, including deposits near the Apollo 15 and 17 landing sites where the water-bearing glass bead samples were collected.

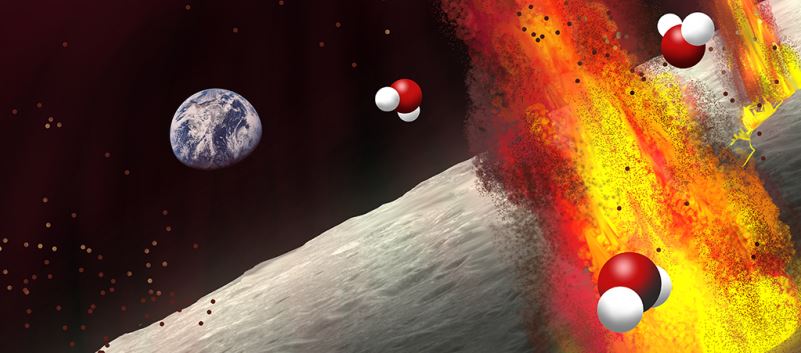

Scientists think the Moon formed from debris left behind after an object about the size of Mars slammed into the Earth very early in solar system history. One of the reasons scientists had assumed the Moon’s interior should be dry is that it seems unlikely that any of the hydrogen needed to form water could have survived the heat of that impact. If large amounts of water remain, that would raise doubt about the existing hypothesis of moon formation.

“The key question is whether those Apollo samples represent the bulk conditions of the lunar interior or instead represent unusual or perhaps anomalous water-rich regions within an otherwise ‘dry’ mantle,” said Ralph Milliken, lead author of the new research and an associate professor in Brown University’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. “By looking at the orbital data, we can examine the large pyroclastic deposits on the Moon that were never sampled by the Apollo or Luna missions. The fact that nearly all of them exhibit signatures of water suggests that the Apollo samples are not anomalous, so it may be that the bulk interior of the Moon is wet.”

Comments