Normally when you talk about agriculture, the last thing you want is grey. No grey weather, no grey water, no grey foliage, no grey milk; I think you get the point. I’m here to argue; however, that grey is exactly what modern dairy production needs when it comes to consumers and the media.

I am an animal scientist. I study dairy cattle production. I do the best I can to make decisions based on consideration of facts and consequences. I understand that there are opportunities for compromise, or no single right answer. There can be a grey area. If it’s not grey, the other

options are black and white. I keep hearing this when people discuss the dairy industry: it’s either A or B; hot or cold; chocolate or strawberry; organic or conventional; bST or bST-free…wait, what!?!?

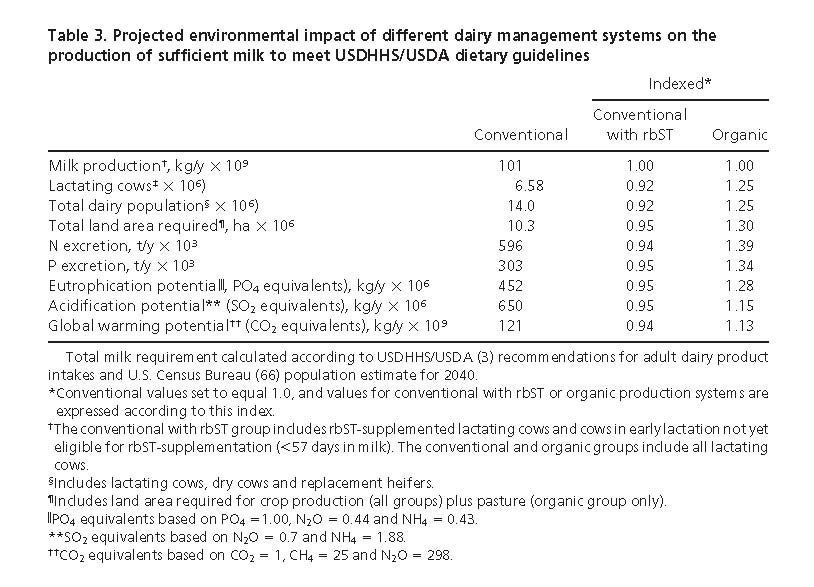

Organic dairy production should not be a black or white issue. Somehow we’re led to believe that it’s either organic or the devil when it comes to milk production. Pro-organic groups would like you to believe that farming practices not qualified as organic are single-handedly destroying our environment and making milk unsafe for consumption. What is grossly ignored, I believe, are the extensive efforts of research institutions, corporations, and individual farmers to improve farming practices and lower the environmental impact, regardless of management structure (Capper et al., 2008; Capper et al., 2009). Did you know that modern dairy production uses only 21% of the animals on only 10% of the land that it took to produce the same amount of milk in 1944 (Capper et al., 2009)? Yes, organic practices can be beneficial to the environment, but so can conventional practices that make good decisions for the better of the land. Rather than switching production to organic practices, which will require much more land and inputs to produce the same amount of product, we should instead support conventional farmers who make responsible decisions which lessen environmental impact. In the end, organic and conventional farmers produce the same exact milk with no compositional differences (Dangour et al., 2009). Do I support farming which has less environmental impact? Of course! Do I think organic is the answer? No. Acknowledge the grey area.

are treated with recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST). Using this technology, cows are able to partition their nutrients towards milk production to produce more units of milk per unit of feed input and manure output (Figure 1). Those who are anti-technology, however, would like you to believe that this process somehow produces mutant milk laden with hormones, despite scientific articles disputing such claims (Daughaday and Barbano, 1990; Vicini et al., 2008). Milk from cows treated with rbST does not have higher levels of the hormone. This is a mute point, however, considering that IF there were higher levels, it would be inactive. Any educated reader of Scientificblogging would have a good understanding of the recombinant process: the bovine

somatotropin hormone, produced by bacteria in the same way that human insulin is made for those suffering from Type I diabetes, would have no biological activity in a human given that the structure of the hormones is different. Additionally, any bST in milk would be completely digested once consumed given that it is simply a protein. Research the grey area.

Figure 1: Relative impacts of conventional, rbST and organic management systems. Source: Capper et al., 2008.

Figure 1: Relative impacts of conventional, rbST and organic management systems. Source: Capper et al., 2008.And since we’re talking about it: hormones in milk are not a black and white issue. How would people react to us putting an end to Vitamin D supplementation in our milk? We should all be thankful that there is no such thing has hormone-free milk. Vitamin D is a hormone and adding this hormone to milk put an end to a majority of infants in the early 1900s having rickets (Holick, 2007). Understand the grey area.

Antibiotics should also not be a black-or-white issue. Through the last decade, our understanding of the consequences of improper antibiotic use has improved, due to our misuse in human medicine (Levy and Marshall, 2004). Antibiotics are now used in a safe and targeted manner to keep ourselves and our animals healthy. There is one black-or-white issue to discuss here: there are no antibiotics in any milk. Period. No matter what. No discussion. Milk is rigorously tested from the moment it leaves the farm until it is packaged for consumption or use in other dairy products. Any dairy product reaching your shelf has been entirely antibiotic-free since the moment it left the farm. When your child is sick with a bacterial infection, you (under the consultation of a doctor), give the child antibiotics in the proper manner to most effectively cure the disease. This process is identical to the choices farmers make with antibiotic use. Not all antibiotic use is bad. Recognize the possibility of a grey area.

One of the most frustrating aspects of this black or white environment is the blindfolding of consumers such that their choices in the supermarket are becoming limited. In every major grocery chain in my town, I am unable to buy milk from cows that were given rbST, despite my beliefs that doing so would actually benefit the environment (Capper et al., 2008). And how about the lower-income consumer who, because of the price differential (upwards of over $1/half-gallon according to reporting over the first 8 months of 2009 by the USDA), is unable to buy organically produced goods? Should they be fearful of purchasing conventionally produced goods? It’s much easier to place labels on products declaring them to be “free” of something rather than educate the consumer on the lack of nutritional differences; and the broader consequences of that label should be considered. Consider the grey area.

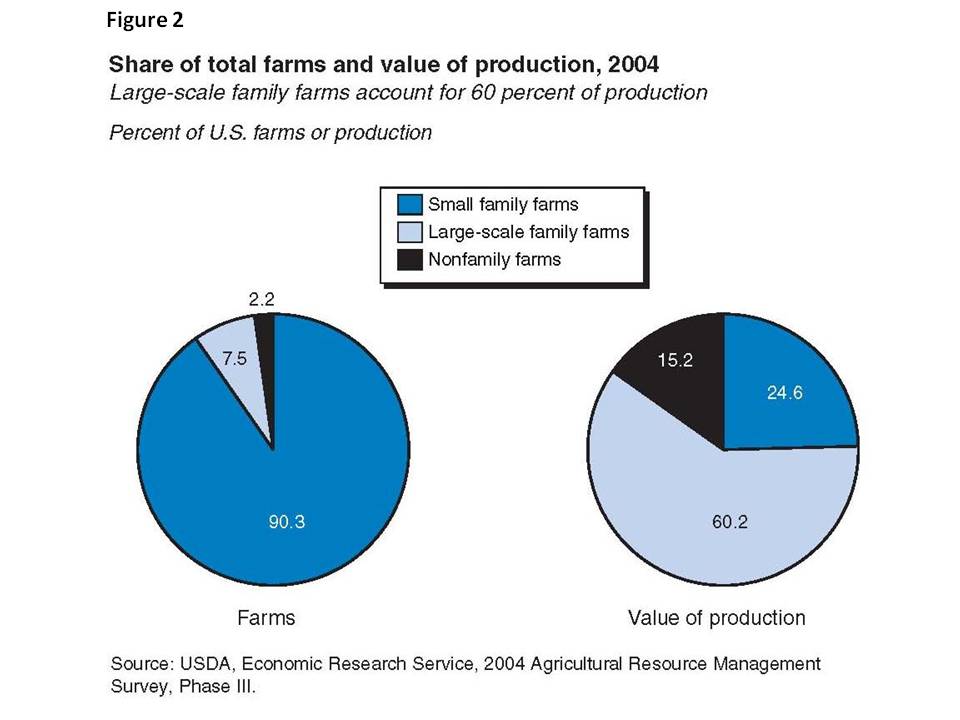

I will add a few final comments regarding the most important player here: the farmer.Even for the consumer, this is the person most forgotten; despite the fact that 98% of farms in the U.S. are family owned (Figure 2, 2007 USDA Family Farms Economic Research Service Report).

The average person has a severe disconnect with where their food comes from. The lack of an “Agriculture” topic on ScientificBlogging, is another example. We forget how our food ends up on our table, but yet we’re the first to criticize it. Most times I see individuals choosing one side or another in an argument due to lack of understanding of the issue or question. For those of you reading this who are passionately anti-conventional agriculture, I ask you when was the last time you were on an agricultural facility? And how many of those locations have you visited? How many conversations have you had with farmers; the people with the dirt under their nails, sore muscles, and bruises as the badges of their difficult profession? After you carefully evaluate your answers to those questions, then I ask you who should be in charge of making on-farm decisions about which technologies to implement and management practices to follow? Do you make it a habit of telling others how they should do their job?

The average person has a severe disconnect with where their food comes from. The lack of an “Agriculture” topic on ScientificBlogging, is another example. We forget how our food ends up on our table, but yet we’re the first to criticize it. Most times I see individuals choosing one side or another in an argument due to lack of understanding of the issue or question. For those of you reading this who are passionately anti-conventional agriculture, I ask you when was the last time you were on an agricultural facility? And how many of those locations have you visited? How many conversations have you had with farmers; the people with the dirt under their nails, sore muscles, and bruises as the badges of their difficult profession? After you carefully evaluate your answers to those questions, then I ask you who should be in charge of making on-farm decisions about which technologies to implement and management practices to follow? Do you make it a habit of telling others how they should do their job?Perhaps the one good thing that will come out of all of this misunderstanding is an increased consumer consciousness about where their food comes from. It IS your responsibility to ask scientists and farmers questions so that we can do a better job. It is NOT your responsibility to fall victim to sexy headlines and bandwagon campaigns.I have faith that today’s farmer will come out of this time of crisis stronger than ever. I can only hope that you, as the consumer, can begin to see the grey in things and will come out with the best attribute of all: truly understanding where your food comes from. It’s not all black-and-white. Know the grey area.

References

Capper, J. L., R. A. Cady, and D. E. Bauman. 2009. The environmental impact of dairy production: 1944 compared with 2007. J. Anim Sci. 87:2160-2167.

Capper, J. L., E. Castaneda-Gutierrez, R. A. Cady, and D. E. Bauman. 2008. The environmental

impact of recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST) use in dairy production. Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9668-9673.

Dangour, A. D., S. K. Dodhia, A. Hayter, E. Allen, K. Lock, and R. Uauy. 2009. Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90:680-685.

Daughaday, William H. and D.M. Barbano. 1990. Bovine Somatotropin Supplementation of Dairy Cows: Is the Milk Safe? JAMA 264:1003-1005.

Holick, Michael F. 2007. Vitamin D Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:266-281.

Levy, S. B. and B. Marshall. 2004. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10:S122-S129.

USDA. 2007. America’s Diverse Family Farms. Economic Research Service Economic Information Bulletin Number 26.

Vicini, J., T. Etherton, P. Kris-Etherton, J. Ballam, S. Denham, R. Staub, D. Goldstein, R. Cady, M. McGrath, and M. Lucy. 2008. Survey of retail milk composition as affected by label claims regarding farm-management practices. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 108:1198-1203.