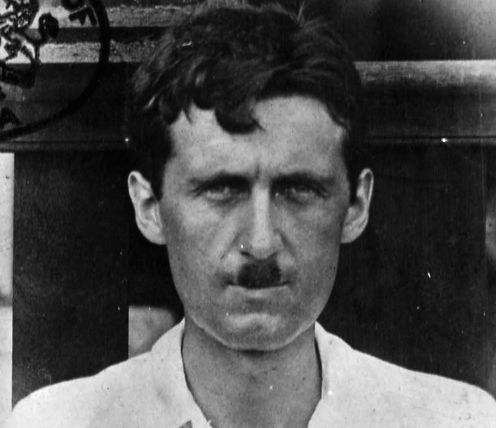

Not Hitler. This is Edward Burton, also known as Eric Arthur Blair, also known as George Orwell

By Luke Seaber, University College London

If you had been walking down Mile End Road in London on Saturday December 19, 1931, you would have witnessed a scene common in the days before Christmas across Britain.

A man who had celebrated a little too much a little too early was taken away by the police after he had consumed four or five pints and the best part of a small bottle of whisky and made a nuisance of himself. But this wasn’t quite as run of the mill as it seemed.

There was nothing in the incident that the police had not seen a hundred times before. Nor was it anything new to those sitting on the bench at Old Street Police Court, where a chastened casual fish porter at Billingsgate, one Edward Burton, was fined six shillings the Monday following – six shillings he couldn’t pay.

Fish porter. Author provided

Had anyone been keeping track of his life in London, they might have jumped to certain conclusions about this Edward Burton. He slept in dosshouses or rough in Trafalgar Square. He was friends with tramps and on at least one occasion went down to Kent to go hop-picking with them. But they may also have noticed that his accent sometimes strangely sounded like that of an educated man and that there was perhaps a slight air of mystery about him.

Had he come down in the world somehow? He showed a knowledge of Hindi – perhaps he was a remittance man who had come sloping back to England from abroad to his family’s despair and shame.

He had too something of a military bearing: maybe he had been one of Kipling’s “gentleman rankers” who had become part of a less exotic and less romanticized “legion of the lost ones”.

Edward Burton was all and none of this. The name was a pseudonym for one Eric Arthur Blair, who would later become famous under another pseudonym. Burton was in fact George Orwell, researching the streets in what would eventually result in Down and Out in Paris and London, his writings on poverty in the two cities. His original intention to experience prison life failed, despite his conviction for being “drunk and incapable”. But he did turn his adventure in police cells into an unpublished article, “Clink”.

Police records December 21. Author provided

“Clink”, like all of Orwell’s accounts of his time spent “down and out”, poses the same problem to readers that nearly all such texts do. The tradition of such accounts of incognito social investigation began with James Greenwood’s 1866 “A Night in a Workhouse”, which in many respects created modern investigative journalism. The genre relies upon presenting itself as a true account of the authors’ experiences, but the reader has to take them on trust. We have to accept them as non-fiction, as reportage, a degree of confidence in the author’s honesty is demanded.

Even Down and Out in Paris and London, a book celebrated for its unflinching portrayal of lived reality, has this problem: we may trust Orwell’s account of his experiences, but evidence has been sorely lacking to prove that we are right to do so.

But my research in the London Metropolitan Archives has led me to an exception – the discovery of Edward Burton’s case.

The court record shows that Orwell was extraordinarily accurate in his descriptions. We can identify many of those whom he describes meeting. For example: the “ugly Belgian youth charged with obstructing traffic with a barrow” is clearly Pierre Sussman, aged 20, who pleaded guilty to obstructing Shoreditch High Street with a barrow. The “youth who had stabbed his tart in the stomach” must be one Joseph William McGowan, although Orwell and his cellmates were sadly wrong in their belief that “she was likely to recover” – his accusation was in fact of murder. The “florid, smart man” who was “a public house guv’nor” and had “embezzled the Christmas Club money” can be identified as Harry Templeman, landlord of the Vicar of Wakefield in Bethnal Green.

This discovery allows us to reach the conclusion that Orwell is reliable. Here, at least, he is impeccably honest, and this sheds some light on to the whole question of writers’ reliability when representing “the poor”.

Luke Seaber, Tutor in Modern European Culture at University College London, received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA Grant Agreement No 298208.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments