The word "pesticide" conjures up negative, scary images. These images come from old organophosphate insecticides of the 1960s that killed fish and birds and caused farm worker illness. These are sorely outdated images. What most people don't know is how much safer the new generations of pesticides are.

In fact, scores of old materials have been withdrawn from the market or banned long ago. The new products are mostly compounds with extremely low mammalian toxicity and benign environmental profiles. Today's pesticides are not your grandfather's or even your father's pesticides.

Fortunately, you don't have to take my word for this. There are some excellent sources of public data on this topic. These products emerged from an on-going chemical discovery effort involving billions of dollars of investment over decades.

Pesticides From A Consumer Perspective

One source of information about pesticides is a huge, annual sampling and testing exercise that the USDA carries out to look at what pesticide residues can be found in the food supply. I have previously posted an analysis of that that data set from 2010 (latest available). It shows that the residues that can be detected on US foods are at such low levels relative to conservative tolerances, there is no reason for US consumers to worry about them.

What Sort of Pesticides Are Farmers Actually Using Today?

When a recent, Stanford, meta-study cast doubt on the nutritional advantage of organic foods, some consumers stated that it is still worth it to buy organic because it doesn't have pesticides. Many, perhaps most, consumers believe that organic means "no pesticides." This is simply not true - though it is a convenient fiction for some marketers and advocates. There are many pesticides that are allowed to be used on organic crops.

One of the best ways to look at what is being used in both conventional and organic farming is to look at the extensive and transparent, California Pesticide Information Portal (CalPip). California has a tremendous diversity of crops and also a very large share of the organic market. It is a source for data which comes from mandatory reporting of all commercial pesticide use in the state. CalPip posted two lists of the top 100 pesticides used - one based on total pounds applied and one based on the total number of acres treated. I created a list that combined the two without the surfactants or other spray additives. That left 104 materials. I then looked up the publicly available, MSDS documents (Material Safety Data Sheets) to get the acute toxicity (oral ALD50) for each of the products (see graph below).

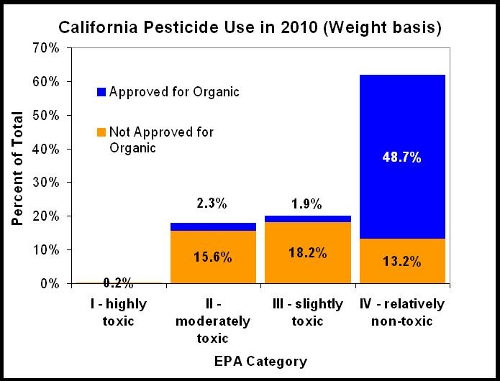

The EPA defines a range of toxicity categories from I to IV, with IV being the least toxic (essentially non-toxic to mammals, but their terminology is classic regulatory cautious). On a weight basis, the largest share of pesticides used in California in 2010 fall into this category (62%). The blue part of the bar includes products which allowed for both organic and conventional farms.

About 1/3 of all the pesticides used in California in 2010 fall into the "slightly toxic" or "moderately toxic" categories. Note that there are organic products in these toxicity categories as well. Most of the organic pesticides in categories II and II are copper salts (copper sulfate, copper hydroxide...). These are old products which the EPA still allows with some restrictions because of copper's issues with toxicity to aquatic invertebrates and environmental persistence. Conventional growers can control the same plant diseases that organic growers treat with coppers using various category IV products which are less toxic which have benign environmental profiles. Why would organic growers use pesticides with somewhat more risk issues than conventional? Because the criterion for organic approval has nothing to do with safety as such. It is all about whether it meets a certain definition of "natural." As we will see later, categories II an III are not all that scary, but it is worth noting that organic does not automatically mean better from a pesticide perspective.

Note that only 0.2% of the commonly used chemicals in California fall into the "Highly Toxic" category, and those are used under strict limits to prevent any form of unwanted exposure. Just for interest sake; however, Vitamin D3 would fall into this category if it were a pesticide.

How Toxic Are These Different Categories?

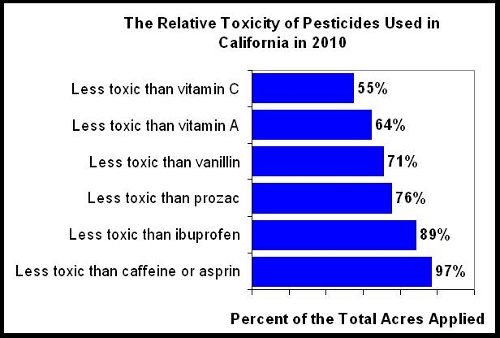

It is not that easy for most people to relate to these EPA category descriptions, so it is useful to make comparisons between pesticides and familiar chemicals in foods and pharmaceuticals (see graph below).

Vitamin C is something which many people take in large, 250-1000 mg doses on a regular basis. Fifty-five percent (55%) of the pesticides used in California in 2010 were less toxic than Vitamin C. Sixty-four percents (64%) were less toxic than vitamin A. Seventy-one percent (71%) were less toxic than the vanillin in ice cream or lattes. Seventy-six percent (76%) of the pesticides were less toxic than prozac and 89% were less toxic than the ibuprofen in products like Advil. Ninety-seven percent (97%) of California pesticide use in 2010 was with products that are less toxic than the caffeine in our daily coffee, the aspirin many take regularly, or the capsaicin in hot sauces or curries. This is not the sort of image that most people visualize when they hear the word "pesticides."

Of course, acute oral toxicity is only one of many dimensions of the EPA risk assessment that is behind all product registrations and reviews. That is why, from a consumer health point of view, the comparison of residue levels to a tolerance is the most appropriate statistic by which to judge consumer safety (it factors in various forms of chronic exposure and the nature of the crop itself..). People are also concerned about combinations of chemicals, but our diets contain more complex combinations of natural plant-made chemicals at much higher concentrations. The beneficial aspects of eating things like fresh produce far outweigh any concerns about the pesticide residues that are in either organic or conventional foods.

What About Farm Workers or the Environment?

The people who tend our crops are certainly exposed to pesticides far more than any consumer. What about them? If one looks at the data for exposure via skin or breathing, a similar pattern emerges to that for oral toxicity - modern chemistries are low in hazard and thus in risk. There are also label restrictions that prevent workers from being exposed to the more hazardous materials (e.g. what protective clothing is required and how long after a spray before anyone can re-enter the field). All the registered pesticides are also extensively studied in terms of their effects on "non-target" organisms and their environmental fate. The rules for how any given pesticide can be used (the label requirements) factor in worker and environmental risk. Once again, the sort of issues that were common in the 1960s are not at all reflective of the modern situation. Some organically approved pesticides have their own worker and environmental issues which are also mitigated by the same sorts of EPA label restrictions.

Are Pesticides Really Needed Anyway?

Yes, they certainly are. Farmers use many other methods than pesticides to control pests (I'll be writing about that soon), but without pesticides our farms would be far less efficient in terms of resource-use-efficiency (land, water, fuel, fertilizers, labor). That is why both organic and conventional farmers often need to use pesticides. Again, the organic pesticide list was not created based on its risk profile, so there are many cases where the conventional options are as low or lower in risk than the organic option.

So, overall, the “its all about pesticides” argument for buying organic is not compelling in a modern time-frame. If someone wants to spend the extra money for organic, that is their choice. Someone who does not want to by organic should feel neither guilt nor fear about that decision. It is a choice that is well supported by the science.

Spraying image from the USDA-ARS. Graphs by Steve Savage based on CalPip Data. I'm also happy to share my data files with those that are interested. You are welcome to comment here and/or to write me at savage.sd@gmail.com

Comments