How many organisms live on this little planet of ours? A pretty straight-forward question. The answer, however, is much more enigmatic. Estimates range from a careful 3 million to a huge 100 million. Now, a new approach, published in PLoS Biology, has yielded another estimate. The new method used resulted in an estimate of 8.7 million (± 1.3 million SE) eukaryotic species, of which 2.2 million (± 0.18 million SE) can be found in the oceans. As about 1.2 million species are catalogued, this would mean that roughly 86% of organisms on earth still await discovery, a number that rises to 91% in the oceans.

Where do these numbers come from?

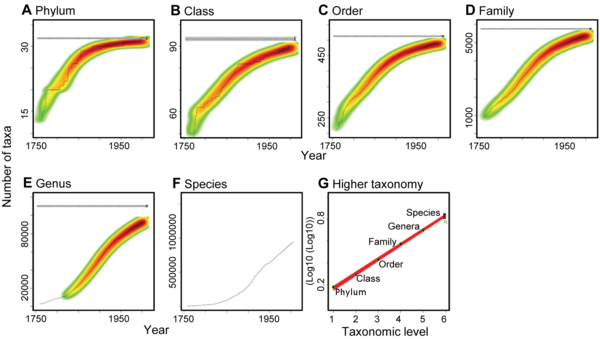

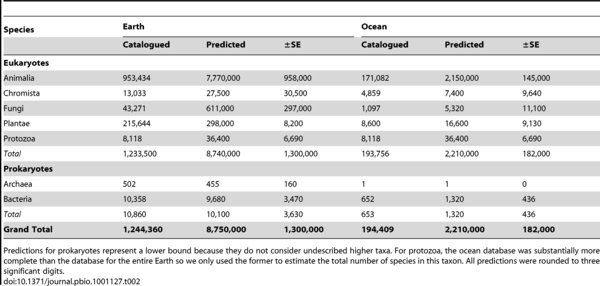

The new method is based on the higher taxonomic classification of species, which appears to follow a predictable pattern from which the total number of species in a certain taxonomic group can be estimated. After compiling full taxonomic classifications of about 1.2 million species, accumulation curves of taxa were assembled (see figure 1). Based on the decrease in completeness as lower taxonomic classifications are considered, species numbers can be estimated. This yielded the estimates in table 1.

Figure 1: A to F: accumulation curves for different taxonomic classifications. G: relationship between the number of taxa and the taxonomic rank. Black circles represent the consensus number of taxa, green circles the catalogued number of taxa.

(Source: Mora et al., 2011)

Table 1: currently catalogued and predicted number of species on earth.

(Source: Mora et al., 2011)

The authors also mention possible limitations, which can influence the robustness and interpretation of their results. These are:

- Species definition.

- Changes in higher taxonomy.

- Changes in taxonomic effort.

- Completeness of taxonomic inventories.

- Subjectivityin the Linnean system of classification.

The authors conclude:

Though remarkable efforts and progress have been made, a further closing of this knowledge gap will require a renewed interest in exploration and taxonomy by both researchers and funding agencies, and a continuing effort to catalogue existing biodiversity data in publicly available databases.

But why would we care about how many species there are? In a primer about the article, also published in PLoS Biology, Oxford zoologist Robert M. May briefly answers this question.

Ultimately, why should we care about how many species are alive on earth today, and about how many of them are known to us? One notable Victorian physicist (I will be merciful and not name him) opined that such a quest is little more than stamp collecting. To the contrary, we increasingly recognise that such knowledge is important for full understanding of the ecological and evolutionary processes which created, and which are struggling to maintain, the diverse biological riches we are heir to. Such biodiversity is much more than beauty and wonder, important though that is. It also underpins ecosystem services that—although not counted in conventional GDP—humanity is dependent upon.

He praised the imagination and simplicity of the method developed by Mora et al. (2011), but does mention that:

...this tentative assessment makes no allowance for accelerating extinction rates… the task of cataloguing our planet's biological richness will be simplified by its winnowing.

Overall, he concludes:

The essential fact is that, if we are to meet the challenges facing tomorrow's world, we need a clearer understanding of how many species there are—both on land and in the even less well-studied oceans—underpinning the structure and functioning of ecosystems. Mora et al.'s interesting new approach to assessing the magnitude of this task is thus very helpful.

References

May, R.M. (2011). Why Worry about How Many Species and Their Loss? PLoS Biology. 9(8):e1001130. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001130. (Click here for the article)

Mora, C.; Tittensor, D.P.; Adl, S.; Simpson, A.G.B .and Worm, B. (2011). How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean? PLoS Biology. 9(8):e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. (Click here for the article)

Comments