So why are more boys born at the end of wars? Now we have to leave the comfort of facts, and are left with contested opinions.

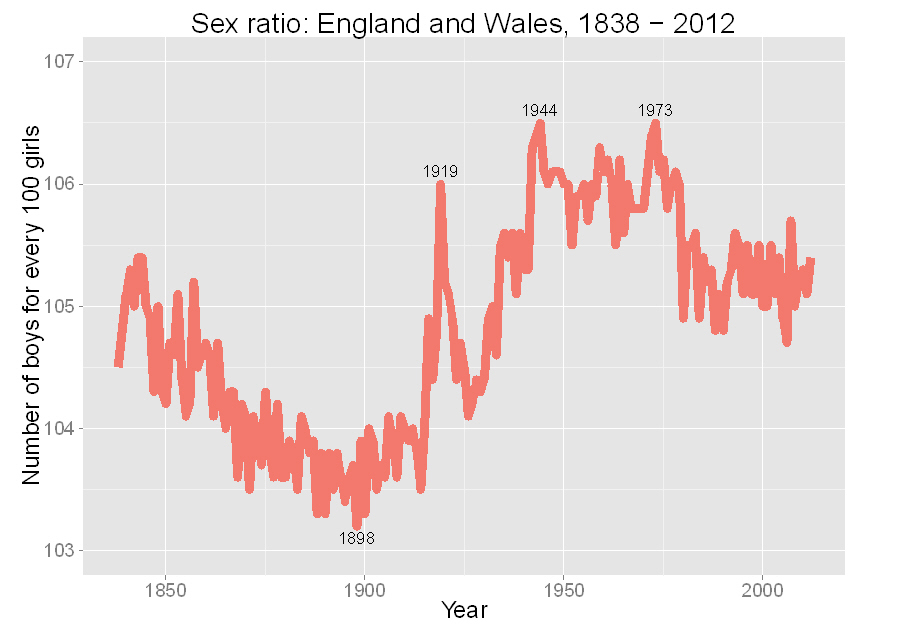

Reliable official statistics on births in England and Wales have been available since the late 1830s, and the graph below shows the sex ratio from then until 2012. There are clear spikes at the end of the two World Wars, but also around 1973, while there is also a steady dip towards the end of the nineteenth century – we’ll come to that later.

[Data: Office for National Statistics]

The pattern in the US shows a similar pattern: a peak in 1946, and then again in the early 1970s. Other belligerents showed an excess of males following World War 1.

What is going on? Is some strange force replacing the males lost in warfare with new baby boys, ready to do their bit when the time comes round again?

This may not be as crazy as it sounds - the ‘Trivers-Willard’ evolutionary theory says that offspring tend marginally towards the gender that is favoured by maternal circumstances, and more boys will do better in a society short of males – we don't need to bring God into it, just Darwin.

But extra boys are also born to younger parents, early on in marriage, and to those who conceive quickly, and this has led some to conclude that, rather than evolutionary pressures, it is the intensity of sexual activity that can, by a small amount, lead to more boys - William James has been a major proponent of this idea. An explanation for this comes from the subtle observation that intense sexual activity means that it is more likely that conception will occur before the most fertile time of the monthly cycle, as the woman may be pregnant by then. There is evidence that, possibly for hormonal reasons, such conceptions are slightly more likely to be boys.

It doesn’t take much imagination to suppose that the ends of wars, with servicemen home on leave or returning home, are associated with fairly intense sex – more babies were born in the UK in 1919 than any other year in history. Put all these together and you get the conclusion – frantic fornication breeds boys.

But what about the peak in the early 1970s? The late 1960s and early 1970s was a time when age at first marriage and age at first birth reached an all-time minimum in the UK (and when gonorrhoea rates reached a peak). There was intense sexual activity among young people, and this could explain the spike in the 1970s.

But perhaps most interesting is what was going on in the late Victorian period. At that time there was a precipitous drop in fertility, from around five to around two children born per woman: this dramatic change has always been rather a mystery as there appears to have been very little use of artificial contraception.

But the graph shows that is exactly when the sex-ratio fell to an all-time low and this, in contrast to the end of wars, suggests that there was simply less sex going on, reaching a low at the turn of the century.

So the fact that the sex-ratio reached a minimum gives support to the idea that the prevailing ‘culture of abstinence’ really did mean less sex.

But this must remain an opinion rather than a fact.

Sex by Numbers by David Spiegelhalter is published by Profile Books and the Wellcome Collection. There's a neat animation of some of the data.

Comments