The connection between music and mathematics has been widely known for centuries. Musica Universalis, "music of the spheres", emerged in the Middle Ages as the idea that the proportions in the movements of the celestial bodies -- the sun, moon and planets -- could be viewed as a form of music, inaudible but perfectly harmonious, and more than 200 years ago Pythagoras discovered that pleasing musical intervals could be described using simple ratios.

Three music professors, Clifton Callender at Florida State University, Ian Quinn at Yale University and Dmitri Tymoczko at Princeton University, have devised a new way of analyzing and categorizing music that takes advantage of the deep, complex mathematics they see enmeshed in its very fabric.

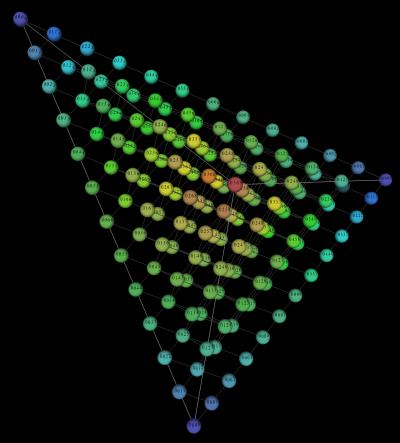

The trio has outlined a method called "geometrical music theory" that translates the language of musical theory into that of contemporary geometry. They take sequences of notes, like chords, rhythms and scales, and categorize them so they can be grouped into "families." They have found a way to assign mathematical structure to these families, so they can then be represented by points in complex geometrical spaces, much the way "x" and "y" coordinates, in the simpler system of high school algebra, correspond to points on a two-dimensional plane.