Recently week pictures were released by Taman Safari Indonesia Animal Hospital & Zoo of two Sumatran tiger cubs and a pair of orangutan babies who have been sharing a home over the last month. All four were orphaned, rescued and are now being housed together at the animal hospital. The snapshots show gentle affection, playful behaviour and even a helpful orangutan feeding a tiger cub.

Recently week pictures were released by Taman Safari Indonesia Animal Hospital & Zoo of two Sumatran tiger cubs and a pair of orangutan babies who have been sharing a home over the last month. All four were orphaned, rescued and are now being housed together at the animal hospital. The snapshots show gentle affection, playful behaviour and even a helpful orangutan feeding a tiger cub.

I am unsure what made the zoo decide to keep these animals together. Perhaps they are experimenting with bonding between species, or may be it was a more logistic matter of space. Regardless, the result is that the four have bonded and there are ethical dilemmas to consider in the near future. What if one of the animals gets aggressive and hurts the other? How will they react to separation if they continue to be as attached to each other as they are now? Holding animals in captivity means severely disrupting their relationship with their natural habitat and social structure. What are our responsibilities as conservationists?

I have long been of two minds about zoos. Like most people, I do not enjoy seeing animals in small cages and cringe when I see large animals display ‘stir crazy’ repetitive behaviour. But the greater good voice in my head says that without zoos we could not create awareness of biodiversity and fund many conservation programs. Of course safari parks are a way to ease the conscience over traditional zoos but despite their growing popularity, they have yet to resolve one of the most striking problems about conservation: a greater value is placed on the conservation of large, ‘sexy’ animals then small, ubiquitous species such as small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, insects, algae or microorganisms.

One example of this slanted perspective on biodiversity is white tigers. These spectacular animals are not a true breed but in fact the result of a rare, recessive genetic anomaly occurring in the more ordinary orange tiger (typically the Bengal Tiger subspecies) . Their fur is white or creamy, they have pink noses, usually blue eyes and black, smoky grey or chocolate-brown stripes or may lack stripes all together.

One example of this slanted perspective on biodiversity is white tigers. These spectacular animals are not a true breed but in fact the result of a rare, recessive genetic anomaly occurring in the more ordinary orange tiger (typically the Bengal Tiger subspecies) . Their fur is white or creamy, they have pink noses, usually blue eyes and black, smoky grey or chocolate-brown stripes or may lack stripes all together.

Until 1951, white tigers were a part of Indian folklore, then a rich Maharajah hunted and captured a white tiger cub and kept it in his palace. This tiger, Mohan, (the Enchanter) is thought to be the only white tiger ever caught in the wild. All white tigers in zoos now are the descendents of Mohan or other captive orange tigers whose recessive genes showed up through breeding programs. The novelty and excitement that such an animal generates means that now while less then 1% of the natural tiger population display the unusual phenotype, a significant number of captive tiger populations are white.

Since wild white tigers are so rare, the current captive breeding pools goes back to only a few individuals and there is so much pressure from zoos and collectors to produce more white tigers, that a host of inbred – related problems have begun to surface including strabismus (cross eyes), retinal degeneration, postural problems, clubbed feet, weakened immune systems and kidney abnormalities.

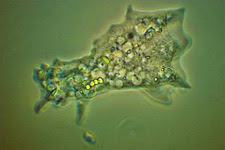

Zoos cater to the public’s demand of BIG! SEXY! FURRY! and FEROCIOUS! And so they over represent animals such as tigers, elephants, hippos and other macrocosmos. To get across the reality of biodiversity we have to make microcosmos interesting for people. Let’s be honest, does a kid runs up to a tank of water full of floating/swimming algae, amoebas and diatoms and get excited? No. Do children enjoy looking at sketches of insects and peering at them through a commplex dissecting microscope? No. So how do we bring microcosmos interesting? One of the best displays I have seen is at the Royal Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. Their Burgess Shale gallery shows colourful large scale models of ‘swimming’ creatures in their marine environment. Visitors walk through the space which is dramatically lit and gives the real sense of being on a sea bed.

Zoos cater to the public’s demand of BIG! SEXY! FURRY! and FEROCIOUS! And so they over represent animals such as tigers, elephants, hippos and other macrocosmos. To get across the reality of biodiversity we have to make microcosmos interesting for people. Let’s be honest, does a kid runs up to a tank of water full of floating/swimming algae, amoebas and diatoms and get excited? No. Do children enjoy looking at sketches of insects and peering at them through a commplex dissecting microscope? No. So how do we bring microcosmos interesting? One of the best displays I have seen is at the Royal Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. Their Burgess Shale gallery shows colourful large scale models of ‘swimming’ creatures in their marine environment. Visitors walk through the space which is dramatically lit and gives the real sense of being on a sea bed.

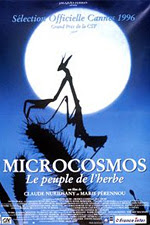

Media also plays a vital part. One of my favourite movies is Claude Nuridsany and Marie Pérennou's 1996 documentary Microcosmos. 15 years of research, 2 years of equipment design, and 3 years of shooting went into making this amazing venture into the hidden world of a French meadow. Especially memorable are a gross scene of slugs kissing and a humorous excerpt of a toiling dung beetle.

Media also plays a vital part. One of my favourite movies is Claude Nuridsany and Marie Pérennou's 1996 documentary Microcosmos. 15 years of research, 2 years of equipment design, and 3 years of shooting went into making this amazing venture into the hidden world of a French meadow. Especially memorable are a gross scene of slugs kissing and a humorous excerpt of a toiling dung beetle.

Large screens, high resolution graphics and even CGI help bring attention to small organisms but I don’t know if amoebas will ever have much of a ‘cool factor’. Anyway, next time I am at the zoo, I am going to spend a little extra time appreciating the small things.

Comments