In a nutshell, the talk identified three (3) problems that were perceived as needing to be addressed to "fix" humanity. In this article, I will discuss the first one.

Problem #1: Death is a BIG problem.

In this discussion, the point is made that it is such a big problem that most people may not see it as such, perhaps because it is so familiar. There were some highly questionable numbers thrown around such as a daily death rate of 150,000 and an annual death rate of 56,000,000 with emphasis on the majority of people (66%) dying of old age. They were questionable, not in regards to their accuracy, but in regards to their relevance. For a philosopher to appeal to pity or consequences, seems a poor beginning for such a topic.

Interestingly enough, the talk assumes a perspective that death is arbitrarily "bad" and doesn't feel the need to even make an argument as to why it is a problem (another appeal to consequences, which seems to be the main thrust of the arguments). Even though human population is increasing to alarming levels, despite the "death rate", it never seems to enter the discussion that eliminating death may bring a different set of problems (no doubt, this will be solved by some other technical miracle). In fairness, it seems that the next set of claims is intended to provide some rationale for what is "bad" about death, although once again, the relevance is questionable.

At this point, Nick Bostrom begins his true flight of fancy by making the following preposterous claim, in equating each lost human life with one book (representing life experience). In 2004, the number of deaths by "natural" causes was 52,000,000 so he immediately concludes that this is equivalent to 52,000,000 "books" being destroyed. He then makes the quantum leap to indicating that the Library of Congress contains 18,000,000 books and consequently in 2004 we lost the equivalent of 3 Libraries of Congress. He does emphasize that this is under estimating the true cost of lost knowledge.

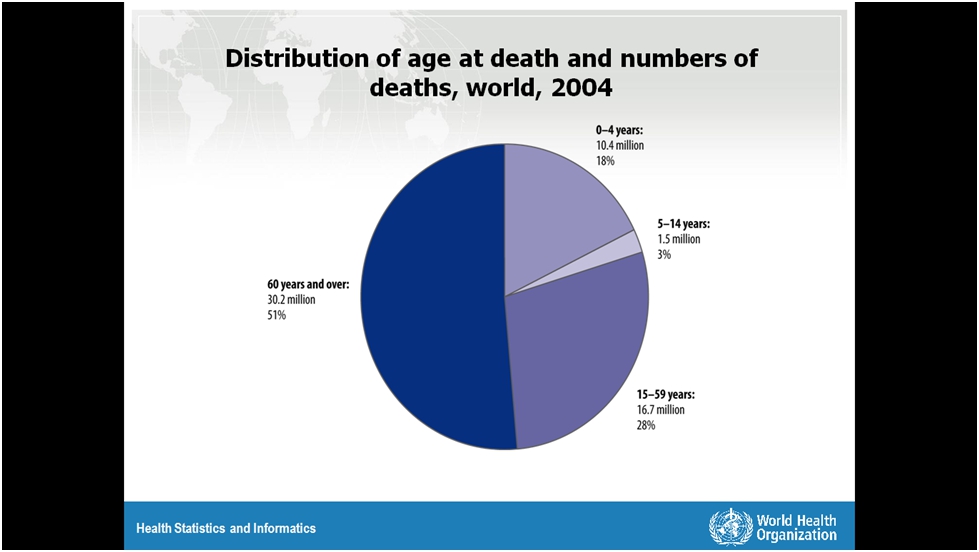

However, before we consider his conclusions, let's look at the numbers themselves. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) gives the death toll in 2004 as 58,800,000, so it's a bit different (about 13%). However, what's interesting is that in the distribution of deaths, 51% occurred in individuals 60 years or older. It gives one pause to consider what exactly is meant by "natural causes" when fully 49% of deaths are under 60 years of age, and 18% (10.4 million) are below the age of 5. Clearly we have a problem with the initial assertion that 66% of deaths

are due to aging. More to the point, it isn't clear what death "due to aging" actually means. Presumably the point is that as our bodies break down over time, rather than some underlying disease condition, then this would qualify. However, without a breakdown by specific criteria, this claim is merely specious.

are due to aging. More to the point, it isn't clear what death "due to aging" actually means. Presumably the point is that as our bodies break down over time, rather than some underlying disease condition, then this would qualify. However, without a breakdown by specific criteria, this claim is merely specious. Going back to the point about the "lost" knowledge is a different matter. Without being overly critical of the information "content" that the majority of people actually possessed, the biggest fallacy in this argument is in suggesting that this was somehow 52,000,000 million unique pieces of knowledge (in fact he even equates it to the sacking and burning of the library in Alexandria).

A legitimate question would be to ask, how much unique (unknown to anyone else or unrecorded) knowledge actually exists in the world, and I would suggest that it is very little. In fact, the irony seems to be lost on Nick Bostrom that this is the point of the Library of Congress existing in the first place.

I also don't intend to trivialize the life experiences that individuals have, but realistically it has little or nothing to do with anyone other than themselves or their families. It is also important to question whether humans are experiencing some sort of information "crisis" as a result of losing all this data, and the answer is obviously; no.

A strong argument can also be made that older generations actually represent a kind of information "bottleneck" as new ideas are being integrated into younger people so that we experience a flow of information that accommodates the corresponding changes in society over time. While it might seem exciting to imagine having a conversation with Sir Isaac Newton, it is our fantasy or vision of him that we are considering. We don't know if he would even be someone we like, and we certainly don't know how well he would've adapted over the centuries to all the work that has occurred since his life. In fact, it would be a legitimate argument to consider how much work might have been stifled by his long-standing academic history (were he immortal). Innovation has rarely been the hallmark of the establishment, which is ultimately what the transhumanist position is advocating.

This criticism doesn't mean that we should give up all technical or medical developments to help people live, or to stop fighting diseases. That presents a false dilemma, so if we are to take this "goal" seriously, then we should be examining what can be done today that doesen't require any additional or future technology. We need to be honest in examining the poor track record we have to doing things that we can actually control right now. There is no technological reason for people to die of starvation. There is no technological reason for people to die in wars/conflicts. There is no technological reason for people to die because of crimes. There is no technological reason for people to die in many vehicular accidents. These are all problems that are not dependent on the future for resolution, but what have we done? We've ignored those problems because they are here now, and we know that we cannot solve them. So to propose some magical technical solution into a future that we can't even envision seems disingenuous.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What about the assumption that death is a problem?

Well clearly it isn't in the general case, since we absolutely depend on it for food in both plants and animals. Presumably, death isn't a problem when it comes to eradicating diseases or pests, so death, itself, can't be the problem. So, we must separate out human death as being the issue to which we want an exception.

Of course, many deaths aren't the result of "natural causes" or simply old age (49%), so how are they to be prevented? Can they actually be prevented without also removing the right for people to behave in any way they choose, including foolishly? We already restrict certain behaviors to control our society by having laws that define what we consider to be criminal activity, so is death a problem for criminals?

This is where the problem becomes more difficult, because if we can rationalize death for one type of human (i.e. criminals), then we have to consider what differentiates the two types and how we determine it. After all, there have been a sufficient number of cases where individuals are on death row in error, so what would it mean to kill an "immortal" human by mistake? Therefore, we are forced to conclude that either ALL humans must be protected from death, including those we consider undesirable, or NO humans can have preferential treatment.

In the first instance, we have to consider that unless we can absolutely control human behavior, then some will behave criminally or, at least, unethically such that an individual may wrongfully be deprived of their life. In addition, we have to consider that, whether being immortal, changes the argument regarding the possibility of rehabilitation. If so, then we may be ethically and morally bound to ensure that no individuals are intentionally killed.

On the other hand, if we argue that some humans can't be allowed to live, then we are faced with the dilemma of determining who makes such a decision? How do we deal with situations where other humans may behave aggressively? Since this behavior can't be assured, it seems we are stuck with the problem that normal deaths will still occur. Interestingly, if that's the case, then the longer the lifespan is, the greater the likelihood is that a person will die a violent death (since death would essentially be an "unnatural" cause).

All in all, the rationale for immortality or increased lifespan is actually a somewhat childish "what if" game which is illustrated by these quotes from Nick Bostrom:

"Imagine what might have become of a Beethoven or a Goethe if they had still been with us today. Maybe they would have developed into rigid old grumps interested exclusively in conversing about the achievements of their youth. But maybe, if they had continued to enjoy health and youthful vitality, they would have continued to grow as men and artists, to reach levels of maturity that we can barely imagine."What seems to be missing from this consideration is that it is precisely because of the limited works that were produced over the time period in question that they have become precious. This seems to be a common fallacy in assuming that "if a little is good, then a lot must be great". If we don't accept this fundamental limitation in our lives, then how are we any different than the rats pressing a "pleasure switch" 18,000 times per day. It is the ultimate in self-indulgence.

http://www.nickbostrom.com/ethics/values.html

"To get a sense that we might be missing out on something important by our tendency to die early, we only have to bring to mind some of the worthwhile things that we could have done or attempted to do if we had had more time. For gardeners, educators, scholars, artists, city planners, and those who simply relish observing and participating in the cultural or political variety shows of life, three scores and ten is often insufficient for seeing even one major project through to completion, let alone for undertaking many such projects in sequence."It's a decidedly myopic view that is based on the idea that the individual that is working on a project should somehow obtain special dispensation to avoid death so that they can continue working. Of course, it fails to consider the large number of people struggling in poverty, or war, or with diseases, that don't have the luxury of worrying about completing such a project, but then ... it isn't their dream, is it?

http://www.nickbostrom.com/ethics/values.html

Perhaps it is time for these "visionaries" to look into the eyes of the younger generation and consider whether they think their ambition is to perpetually be considered "junior" members of whatever project or goal they have for themselves? After all, if your “boss” is immortal, what position can you aspire to?

Of course, I'm neglecting part two of this fantasy, which is perpetual youth. While this has been a point of discussion for probably as long as humans have been alive, it is being revived because of the illusory sway of infinite technological achievement. It doesn't matter that we aren't even remotely close to achieving it, but it's the lure of having youth with immortality that is so captivating.

In a world already bulging at the seams because of population growth, one can only wonder at the effect such indefinite youth can create. Imagine fathering hundreds of children. I would imagine this would be significantly less appealing to women, but one can't tell when medical miracles are available. I can't help but imagine the competition between a 600 year old man and a 30 year old man for a 1,000 year old woman's attention. The mind boggles.

Comments