Pollution is bad but a new study shows that it may some day be a net win for energy.

Like solar panels and quantum computing, hydrogen has been 'ready real soon' for decades but it hasn't happened. Like solar, it is great on paper. Like nuclear fission, hydrogen does not release carbon dioxide and since there is no way that China will stop putting up two new coal plants per week the rest of the world will need to do what communist dictatorships won't; get cleaner. It has other obstacles, like that if it isn't compressed you need a storage tank twice the size of a car to go any distance and if it is compressed...well, don't be nearby in an accident.

Still, those are technical hurdles and the private sector will solve those if it's commercially viable without the mandates and subsidies that have made solar and wind failures. That means hydrogen should not be dismissed.

I use the example of a fax machine because, like Latin, everyone knows of it but no one really uses it so it can have a defined meaning. The first fax machine was very expensive and had no value. There was no one else to fax. Yet eventually they caught on and everyone got one cheap.

That is why proof-of-concepts like this are worth doing. You never know what will take off.

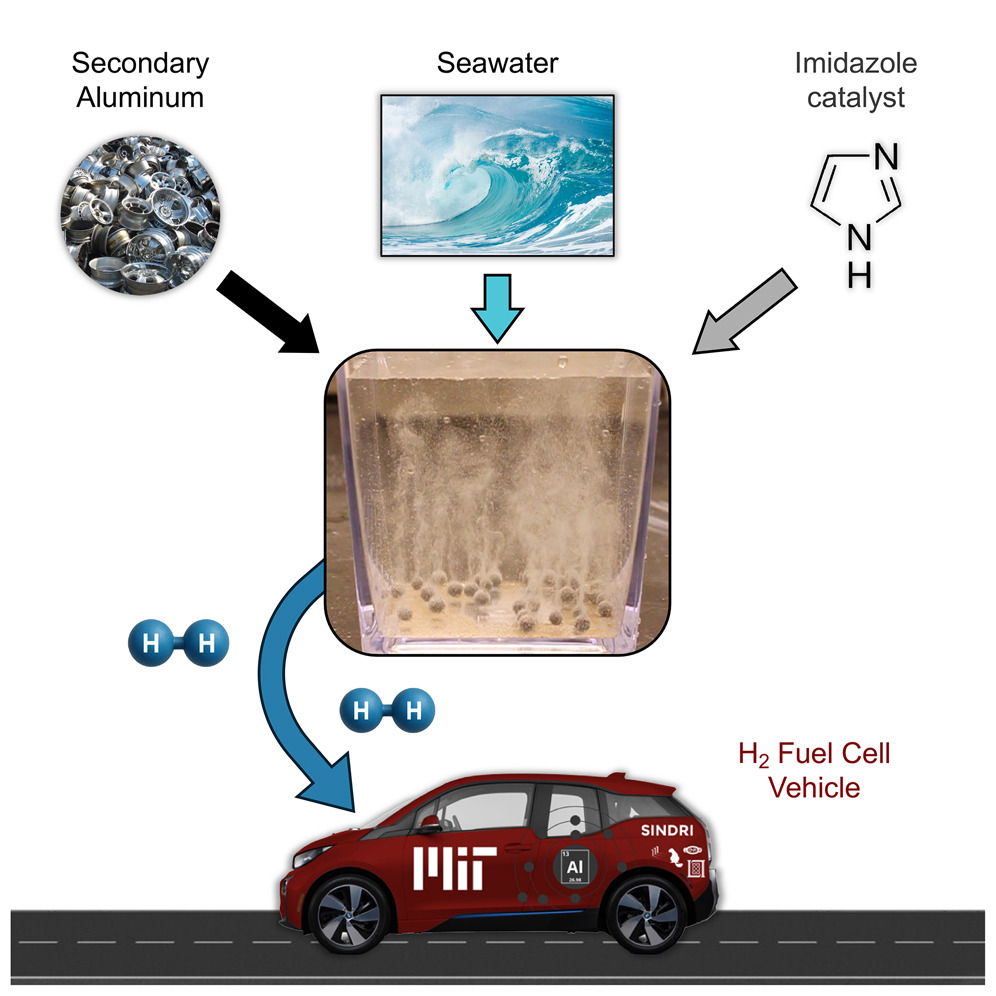

In experiments, MIT engineers combined seawater and soda cans (and coffee) to make hydrogen. Under oxidation, aluminum becomes sealed and it won't mix well with water, that is why cans are good for soda. If that layer is removed, in this case with gallium-indium, aluminum atoms break up water molecules and create aluminum oxide and hydrogen.

It's a nice trick but we have been able to go full metal alchemist and turn lead into gold for half a century and yet no one does it because it loses money. Using an Earthster simulation, they now believe their lab process to turn soda cans into hydrogen can be viable.

Credit: MIT Department of Engineering

They believe they have accounted for the carbon emissions associated with acquiring and processing the cans and using gallium-indium to remove the layer, plus the energy cost of using seawater to produce hydrogen, and getting it to fueling stations. They say it is a fraction of the emissions associated with conventional hydrogen production, but that cost is why hydrogen remains a gimmick. That it only produces 1.45 kilograms of carbon dioxide per kilogram of hydrogen (compared to 11 kilograms of carbon dioxide per kilogram of hydrogen generated using conventional energy) isn't really as important as the fact that it is only enough hydrogen to go between 30 and 50 miles. A cost of $9 per kilogram is still far higher than gasoline, even in California, where gasoline and electricity prices seem to be created by politicians on a dare.

And even if it is only 100% more than gasoline, gallium-indium is a rare-metal allo and is not cheap. Hydrogen this way at scale will make it more expensive, not less. Finally, the Earthster tool is not reliable, it is the Wikipedia of life-cycle assessment.

All of that may be why companies are not lining up to find a roll-out of this.

That does not mean it isn't an intriguing experiment. We just can't believe press releases from universities, even when corporate media rewrites them.

Comments