It's no surprise expecting moms get a little control freak-y. For years before conception women are hammered by claims about how they should be behaving, using correlation and mysticism about epigenetics, or on the really weird anti-science side, claims that they should avoid automobile seats and any food not labeled organic because of increased "risk" of autism if they don't. During pregnancy women are told not to drink coffee or a glass of wine (American women only - European and Asian women don't subscribe to that one) in bizarre 'any detectable proton of a hazard is the same as 100% risk' posturing.

And after the baby is born, it's impossible to list all of the advice and concern coming from every corner, especially from people selling solutions to problems you don't have.

With so much pressure on expecting and new moms, it's no wonder they look to control as much as possible. But is that the same as being OCD? Not really, the concern should instead be that it trivializes OCD to try to care more about mothers. It's entirely possible to do the latter without the former. You can't be 'a little OCD' any more than you can be a little pregnant and being organized because you have so much new work to do is not the same as a compulsion.

Regardless of the cultural milieu, University of British Columbia psychologist Nichole Fairbrother, PhD, is back with her biennial paper on this and advocates that the psychiatric community start screening for OCD - instead of doing what I am doing and telling all those people in culture pillaging expectant mothers with claims about how they are harming an unborn or newborn child unless they buy some product to knock it off.

The first issue with the new results is the same as basically this same paper from 2019 and going back as far as 2008 - that OCD the way they use it is too colloquial. It isn't something that comes and goes, such as when winter ends and you clean everything. Just like two years ago everyone with a bad cold would offhandedly say they have the flu, it is common for people who like to keep things neat to claim they are 'a little OCD' without understanding the implications. This feeds into that issue.

The second problem is that self-reporting temporary behavior is not the same thing as having a disease but if scholars want to claim they are interchangeable, it is possible. We stopped doing symptom-based medicine 60 years ago and psychology needs to move into this century as well. That is why survey results are only ever exploratory, not science. If I survey people right after their homes have been burgled, I could declare that psychiatrists need to start screening people who have been robbed for clinical paranoia. That would be based on statistics but it would not be legitimate.

Finally, this was 580 women in one region of Canada at one period in time.

The differences from prior findings are so large - this means new mothers have 800% more OCD than the general public - that they smell like outlier, an easy thing to have occur with survey results. The authors instead say their 400 percent difference over other surveys is because they asked better questions. This is in defiance of the normal 'everyone believes the data except the collector' hesitance that gnaws at experts. Instead, this group really believe they did better than everyone else's surveys - and that is the most glaring warning sign that they had a result and went looking for evidence to show it.

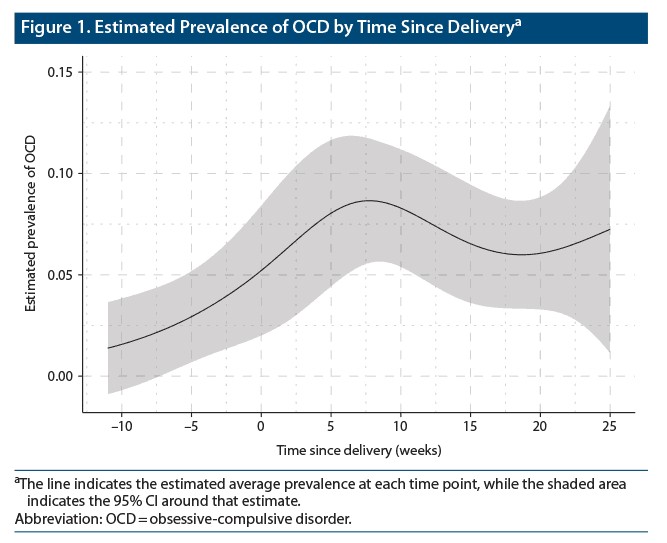

The authors say the peak and ebb is a sign that being OCD may resolve itself naturally. Psychiatrists know that is not how the disease works. Moms with infants simply worry a lot more, and that is perfectly normal - it is not a call to over-medicalize motherhood and have women rushing to psychiatrists for treatment because they worry about their kids.

Comments