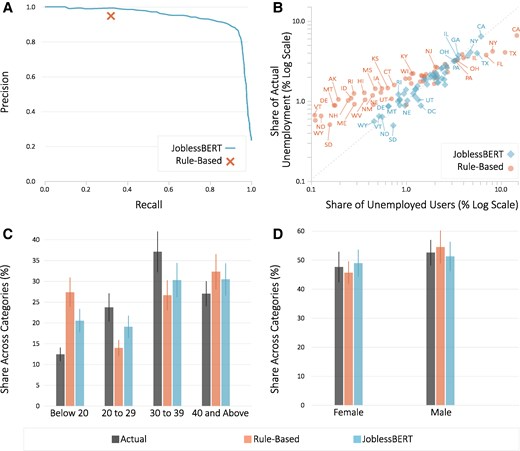

Social Media Is A Faster Source For Unemployment Data Than Government

Social Media Is A Faster Source For Unemployment Data Than GovernmentGovernment unemployment data today are what Nielsen TV ratings were decades ago - a flawed metric...

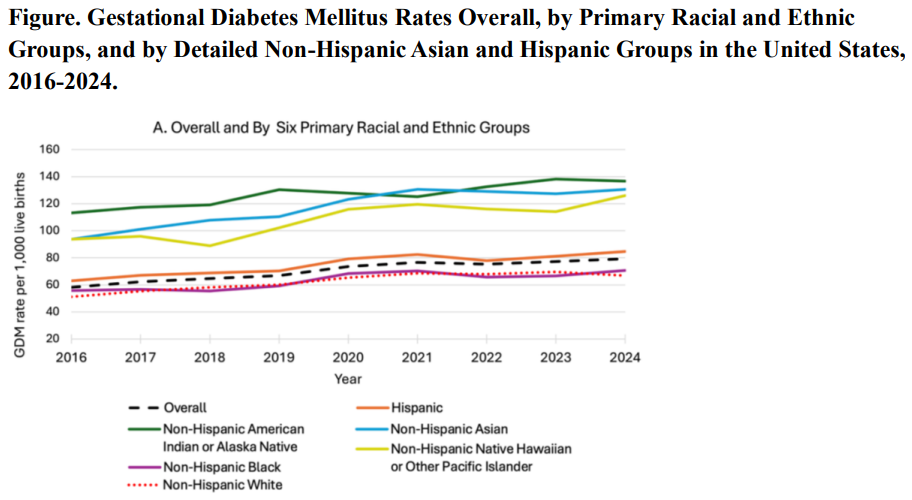

Gestational Diabetes Up 36% In The Last Decade - But Black Women Are Healthiest

Gestational Diabetes Up 36% In The Last Decade - But Black Women Are HealthiestGestational diabetes, a form of glucose intolerance during pregnancy, occurs primarily in women...

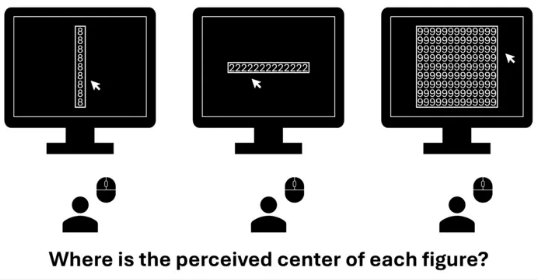

Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive Spaces

Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive SpacesResearchers recently studied the relationship between numerical information in our vision, and...

Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For Food

Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For FoodBees have the reputation of being incredibly organized and spending their days making sure our...