Our brains may not be optimized for recalling things we hear, the way we are good at remembering things we see or touch.

Psychologists doing a study of over 100 University of Iowa college students found that they were less able to recall a variety of sounds the way they could visuals and things they felt.

In an experiment testing short term-memory, participants were asked to listen to pure tones they heard through headphones, look at various shades of red squares, and feel low-intensity vibrations by gripping an aluminum bar.

Each set of tones, squares and vibrations was separated by time delays ranging from one to 32 seconds.

Although students' memory declined across the board when time delays grew longer, the decline was much greater for sounds, and began as early as four to eight seconds after being exposed to them.

While this seems like a short time span, it's akin to forgetting a phone number that wasn't written down, notes corresponding author Amy Poremba, associate professor in the University of Iowa Department of Psychology. "If someone gives you a number, and you dial it right away, you are usually fine. But do anything in between, and the odds are you will have forgotten it."

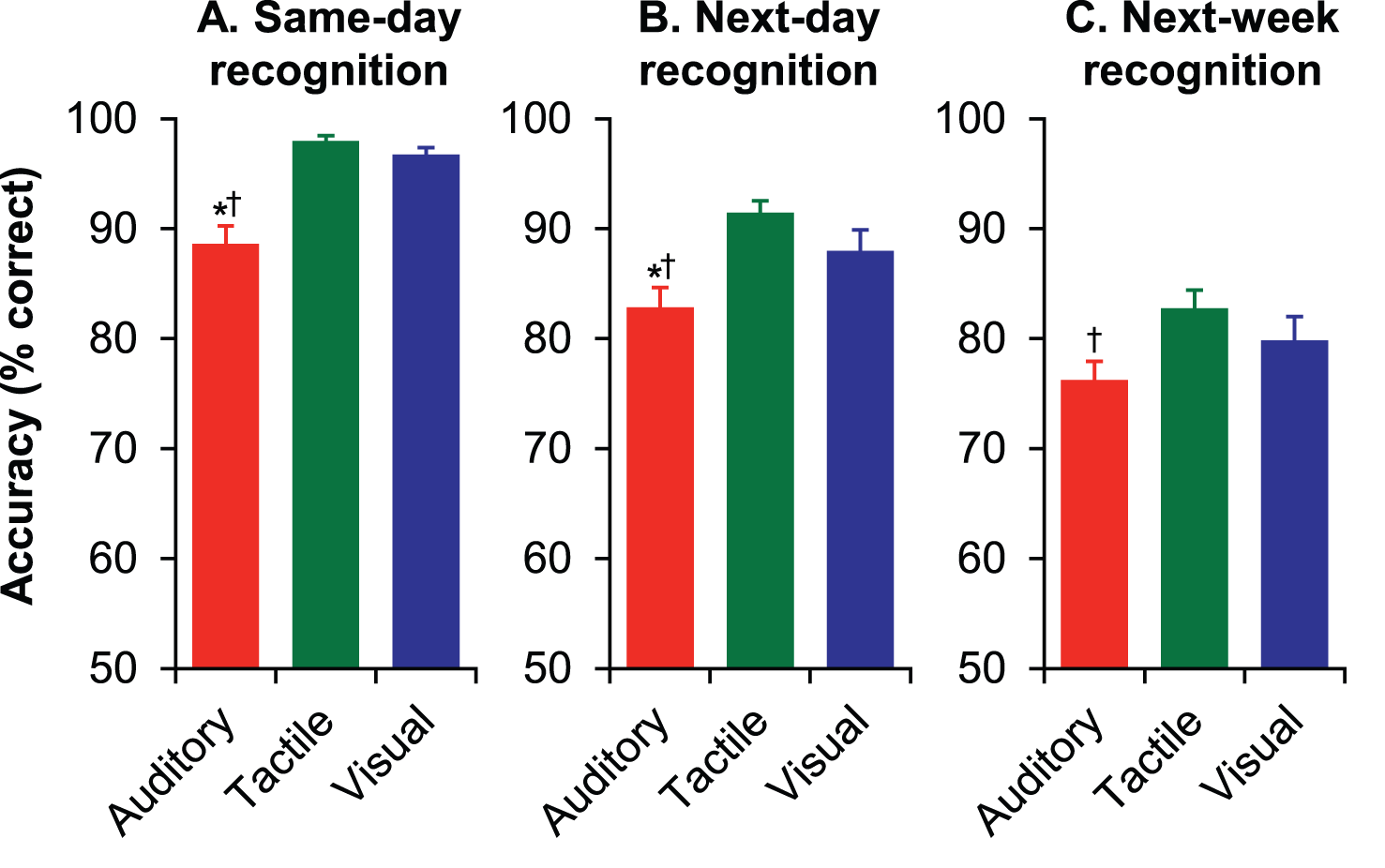

In a second experiment, Poremba and lead author James Bigelow tested participants' memory using things they might encounter on an everyday basis. Students listened to audio recordings of dogs barking, watched silent videos of a basketball game, and, touched and held common objects blocked from view, such as a coffee mug. The researchers found that between an hour and a week later, students were worse at remembering the sounds they had heard, but their memory for visual scenes and tactile objects was about the same.

Both experiments suggest that the way your mind processes and stores sound may be different from the way it process and stores other types of memories. And that could have big implications for educators, design engineers and advertisers alike.

Mean (+ SEM) recognition accuracy among sensory modalities for complex, naturalistic stimuli. (A) When tested immediately after the study phase, recognition accuracy was lower for auditory stimuli than visual or tactile stimuli. (B) Similarly, recognition was lower for auditory stimuli when tested 24 hours after the study phase. (C) When tested one week after the study phase, recognition accuracy was significantly lower for auditory stimuli than tactile stimuli, but the difference between auditory and visual recognition was not significant. Post-hoc tests (p<.05; Bonferroni correction): *Accuracy in the auditory block significantly lower than the tactile block. †Accuracy in the auditory block significantly lower than the visual block. Credit: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089914

"As teachers, we want to assume students will remember everything we say. But if you really want something to be memorable you may need to include a visual or hands-on experience, in addition to auditory information," says Poremba.

Previous research has suggested that humans may have superior visual memory, and that hearing words associated with sounds – rather than hearing the sounds alone – may aid memory. Bigelow and Poremba's study builds upon those findings by confirming that, indeed, we remember less of what we hear, regardless of whether sounds are linked to words.

They say this study is also the first to show that our ability to remember what we touch is roughly equal to our ability to remember what we see. They believe the finding is important because experiments with non-human primates such as monkeys and chimpanzees have shown that they similarly excel at visual and tactile memory tasks, but struggle with auditory tasks.

Based on these observations, the authors believe humans' weakness for remembering sounds likely has its roots in the evolution of the primate brain.

The good news is that if you forgot what your spouse asked you to pick up from the store on the way home, you now have a science excuse.

Comments