The two-inch skull fragment was found at the famed Olduvai Gorge in northern Tanzania, a site that for decades has yielded numerous clues into the evolution of modern humans and is sometimes called `the cradle of mankind.'

The fragment belonged to a 2-year-old child and showed signs of porotic hyperostosis associated with anemia. According to the study, the condition was likely caused by a diet suddenly lacking in meat. The evidence showed that the juvenile's diet was deficient in vitamin B12 and B9. Meat seems to have been cut off during the weaning process so he was not getting the proper nutrients and probably died of malnutrition. Nutritional deficiencies such as anemia are most common at weaning, when children's diets change drastically. The authors suggest that the child may have died at a period when he or she was starting to eat solid foods lacking meat. Alternatively, if the child still depended on the mother's milk, the mother may have been nutritionally deficient for lack of meat.

The analysis offers insights into the evolution of hominins including Homo sapiens. The movement from a scavenger, largely plant-eating lifestyle to a meat-eating one may have provided the protein needed to grow our brains and give us an evolutionary boost.

A long-standing claim is that we became human when we became carnivorous-omnivorous creatures. "Meat eating has always been considered one of the things that made us human, with the protein contributing to the growth of our brains," said Charles Musiba, Ph.D., associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Denver. "Our work shows that 1.5 million years ago we were not opportunistic meat eaters, we were actively hunting and eating meat. Meat eating is associated with brain development. The brain is a large organ and requires a lot of energy. We are beginning to think more about the relationship between brain expansion and a high protein diet."

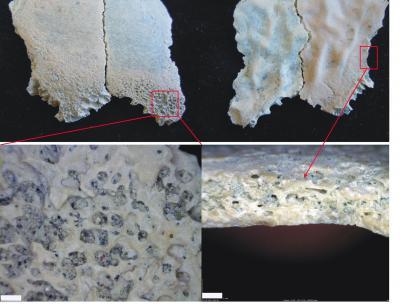

Fragment of a child's skull discovered at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, shows the oldest known evidence of anemia caused by a nutritional deficiency. Credit: Citation: Dominguez-Rodrigo M, Pickering TR, Diez-Martin F, Mabulla A, Musiba C, et al. (2012) Earliest Porotic Hyperostosis on a 1.5-Million-Year-Old Hominin,Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. PLoS ONE 7(10): e46414. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046414

Previous reports showed that early hominids ate meat, but whether it was a regular part of their diet or only consumed sporadically was not certain. The authors suggest that the bone lesions present in this skull fragment provide support for the idea that meat-eating was common enough that not consuming it could lead to anemia.

Humans are one of the few surviving species with such a large brain to body size ratio. Chimpanzees, our closest relatives, eat little meat and have far less brain capacity than humans, which separates us from our distant cousins. "The question is what triggered our meat eating? Was it a changing environment? Was it the expansion of the brain itself? We don't really know."

"The presence of anemia-induced porotic hyperostosis…indicates indirectly that by at least the early Pleistocene meat had become so essential to proper hominin functioning that its paucity or lack led to deleterious pathological conditions," the study said. "Because fossils of very young hominin children are so rare in the early Pleistocene fossil record of East Africa, the occurrence of porotic hyperostosis in one…suggests we have only scratched the surface in our understanding of nutrition and health in ancestral populations of the deep past."

Citation: Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, Travis Rayne Pickering, Fernando Diez-Martín, Audax Mabulla, Charles Musiba, Gonzalo Trancho, Enrique Baquedano, Henry T. Bunn, Doris Barboni, Manuel Santonja, David Uribelarrea, Gail M. Ashley, María del Sol Martínez-Ávila, Rebeca Barba, Agness Gidna, José Yravedra, Carmen Arriaza, 'Earliest Porotic Hyperostosis on a 1.5-Million-Year-Old Hominin, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania', PLoS ONE 7(10): e46414. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046414

Comments