When a sturdy material becomes soft and spongy, it's been damaged in some way. But when it comes to complex fluids and biological cells, things may be different.

By looking at the microscopic building blocks – known as "filaments" – of biopolymer networks, researchers from Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany and the FOM Institute AMOLF in the Netherlands, revealed (Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5060) that such materials soften by undergoing a transition from an entangled spaghetti of filaments to aligned layers of bow-shaped filaments that slide past each other.

In our cells, which contain biopolymer filaments, active flow due to molecular motor proteins can be observed. Since biopolymer filaments are neither fully flexible nor fully rigid like a rod, they are customarily called 'semiflexible' polymers. The viscosity of solutions of semiflexible polymers decreases dramatically at high shear rates a measure of the velocity gradient or the speed differences within a fluid. The effect is called 'shear-thinning'. The flow behaviour of ketchup is a widely known example for this physical phenomenon.

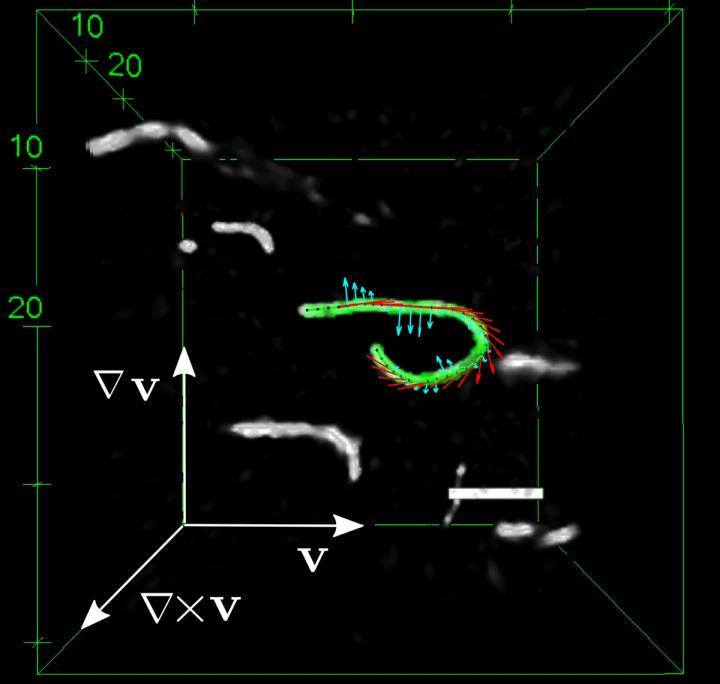

A 3-D confocal microscopic image of fluorescently labeled F-actin filaments, one of which is fully analyzed, in an entangled solution of unlabeled F-actin subjected to shear flow. Credit: Forschungszentrum Jülich

In a collaboration between Prof. Pavlik Lettinga's group in Jülich and Prof. Gijsje Koenderink's group at AMOLF, researchers were able to appreciate the full 3D-shape of the filaments while the system is in flow, providing a wealth of information not previously available.

They found that filaments have an irregular configuration and are intricately entwined with each other while at rest, but that they form hairpin-like structures and detach themselves completely from one another when in flow.

The filaments can then freely slide over each other, which causes the dramatic shear-thinning of semi-flexible polymer solutions.

"We now have a better understanding of why many systems can flow when you distort them, but behave like a solid when you don't", explains Prof. Pavlik Lettinga from the Jülich Institute of Complex Systems. "In industry, flexible polymers are currently used in the main, but with increasing oil prices, industry is looking for alternatives. Many natural systems such as cellulose and amyloids are relatively stiff. Knowledge of the behavior of such systems aids efficient processing and energy saving. With this information, it is now possible to apply a bottom-up approach to the design of a broad range of products."

The scientists set themselves the task of studying tiny biopolymer filaments from a network found in muscle cells whilst set in flow. For this purpose, they marked individual filaments with a fluorescent dye and subsequently observed them using a counter-rotating device under a confocal microscope.

"The results also help us to understand certain biological processes, such as cytoplasmic flow", says Prof. Gijsje Koenderink from AMOLF. "Cytoplasmic flow occurs in many embryos and in large plant cells. Actin filaments or microtubules, together with molecular motor proteins, spontaneously generate flows, which aid in the delivery of organelles and nutrients. Our results provide insight into the microstructural changes that occur during flow."

The methodology opens up the possibility of looking at more complex systems. The researchers plan to study the basic mechanisms of blood clotting, which is an interplay between the network formation of fibrins and red blood cells.

Comments