The "Cambrian explosion," the rapid diversification of animal life in the fossil record 530 million years ago, has by necessity remained the subjective of speculation. We know it happened, but no idea why, we simply know we wouldn't be here without it.

The sudden burst of new life was called "Darwin's dilemma" because it appeared to contradict Sir Charles' gradual evolution by natural selection. The surge in rapid evolution led to the sudden appearance of almost all modern animal groups. Fossils from the Cambrian explosion document the rapid evolution of life on Earth but beyond that it is all conjecture.

A paper in Geology by geology professor Ian Dalziel of The University of Texas at Austin suggests we can thank geology - a major tectonic event could have triggered the rise in sea level and other environmental changes that accompanied the apparent burst of life.

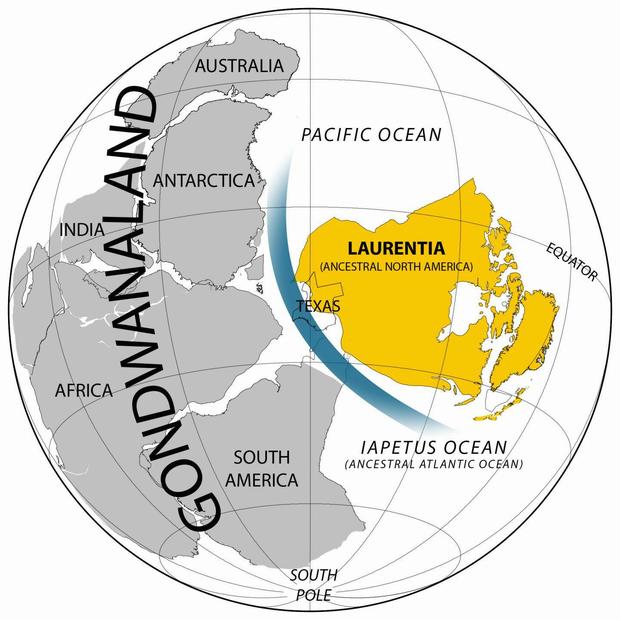

A new paper believes a deep oceanic gateway, shown in blue, developed between the Pacific and Iapetus oceans immediately before the Cambrian sea level rise and explosion of life in the fossil record, isolating Laurentia from the supercontinent Gondwanaland. Credit: Ian Dalziel

"At the boundary between the Precambrian and Cambrian periods, something big happened tectonically that triggered the spreading of shallow ocean water across the continents, which is clearly tied in time and space to the sudden explosion of multicellular, hard-shelled life on the planet," said Dalziel.

Beyond the sea level rise itself, the ancient geologic and geographic changes probably led to a buildup of oxygen in the atmosphere and a change in ocean chemistry, allowing more complex life-forms to evolve, he said.

The paper is the first to integrate geological evidence from five present-day continents — North America, South America, Africa, Australia and Antarctica — in addressing paleogeography at that critical time.

Dalziel proposes that present-day North America was still attached to the southern continents until sometime into the Cambrian period. Current reconstructions of the globe's geography during the early Cambrian show the ancient continent of Laurentia — the ancestral core of North America — as already having separated from the supercontinent Gondwanaland.

In contrast, Dalziel suggests the development of a deep oceanic gateway between the Pacific and Iapetus (ancestral Atlantic) oceans isolated Laurentia in the early Cambrian, a geographic makeover that immediately preceded the global sea level rise and apparent explosion of life.

"The reason people didn't make this connection before was because they hadn't looked at all the rock records on the different present-day continents," he said.

The rock record in Antarctica, for example, comes from the very remote Ellsworth Mountains.

"People have wondered for a long time what rifted off there, and I think it was probably North America, opening up this deep seaway," Dalziel said. "It appears ancient North America was initially attached to Antarctica and part of South America, not to Europe and Africa, as has been widely believed."

Although the new analysis adds to evidence suggesting a massive tectonic shift caused the seas to rise more than half a billion years ago, Dalziel said more research is needed to determine whether this new chain of paleogeographic events can truly explain the sudden rise of multicellular life in the fossil record.

"I'm not claiming this is the ultimate explanation of the Cambrian explosion," Dalziel said. "But it may help to explain what was happening at that time."

Comments