SEATTLE – Pancreas cancer is notoriously impervious to treatment and resists both chemotherapy and radiotherapy. It has also been thought to provide few targets for immune cells, allowing tumors to grow unchecked. But new research from Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center shows that pancreas cancer "veils" itself from the immune system by recruiting specialized immune suppressor cells. The research team also found that removing these cells quickly triggers a spontaneous anti-tumor immune response.

The findings, published Feb. 20 in Gut, give hope for future immunotherapy strategies against this deadly and aggressive cancer.

"The take-home message is that there is a latent immune response against pancreas cancer that can be expressed if we remove its obstacles," said Sunil Hingorani, M.D., Ph.D., an associate member of the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutch, who led the study. "Removing the suppressor cells creates a context that could enable an adoptive immune cell therapy against pancreas cancer."

An almost uniformly deadly cancer

Pancreas cancer is almost uniformly deadly. About 45,000 people are diagnosed with the disease in the U.S. each year. "The mortality rate is essentially the same as the incidence rate," Hingorani noted. Pancreas cancer "doesn't obey the rules" established for other solid tumors, he said: It metastasizes early, resists traditional treatment, and survives quite well on a diminished blood supply.

The tumor builds a fibrous wall around itself which exerts so much pressure that blood vessels entering the tumor are constricted, which also prevents chemotherapy from entering. In addition, scientists have historically had difficulty stimulating a therapeutic immune response against pancreas tumors because they have identified few molecular targets on which to focus the immune attack.

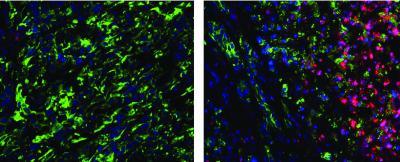

But as the new findings in a mouse model show, pancreas tumors fly under the radar not because they lack targets for the immune system, but because they recruit suppressor cells that keep immune cells at bay. When these immune suppressor cells are removed, helpful immune cells spontaneously move into the tumor and begin their attack.

Activating a T-cell response against the cancer

Pancreas cancer is nearly always diagnosed at very late stages, which has made its development hard to study. To gain insight into these aggressive tumors, Hingorani's team pioneered the development of a genetic mouse model of pancreas cancer. Previous work in the model led to their discovery of an enzyme that can make pancreas tumors more permeable to chemotherapy. The group turned again to this model to learn more about how pancreas tumors interact with the immune system.

From their earlier work, Hingorani's team knew that several different types of immunosuppressive cells infiltrate pancreas tumors. Together with immunologist Philip Greenberg, M.D., a member of Fred Hutch's Clinical Research Division, they have begun studying ways to target these inhibitory cells. As Ingunn Stromnes, Ph.D., the postdoctoral researcher co-mentored by Hingorani and Greenberg who spearheaded this latest study, watched pancreas tumors develop in mice, she saw that one cell type stood out. Descended from bone marrow cells and dubbed granulocyte-myeloid-derived suppressor cells (Gr-MDSCs), these cells jumped in number as pancreas tumors turned invasive. Stromnes discovered the pancreas tumors were orchestrating the accumulation of these suppressor cells by releasing a protein known as granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which attracted the Gr-MDSCs.

Co-authors Philip Greenberg, M.D., Ingunn Stromnes, Ph.D., and Sunil Hingorani, M.D., Ph.D., all of the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

(Photo Credit: Robert Hood/Fred Hutch)

Strikingly, the Gr-MDSCs actively worked against T cells, a class of immune cell central to many immunotherapy strategies. T cells are often harnessed to fight tumors because they can recognize very specific molecules and destroy any cells expressing those molecules. But Gr-MDSCs prevented T cells from dividing and even induced their death.

Stromnes found this effect could be reversed, however, and the T-cell response activated, by depleting Gr-MDSCs. When she did so, she saw evidence not only that the T cells could now enter the tumors, but also that the tumors showed evidence of the type of cellular damage the T cells are designed to mete out.

"The findings are important because they show that the tumor microenvironment itself, and in particular a specific subset of cells in the tumor, is preventing T cells from trafficking to the tumor and mounting a response," Stromnes said. Importantly, humans also possess cells very similar to Gr-MDSCs, which strengthens the case that similar strategies could impact human pancreas cancer. Additionally, the damage wreaked on Gr-MDSC-depleted tumors appeared to release some of the pressure inside the tumor, allowing crushed blood vessels to open again and providing a potential avenue for chemotherapy.

'We want to put as big a hurt on pancreas cancer as possible'

The results are a backbone on which the team can begin designing a multipronged approach to pancreas cancer therapies, Stromnes noted. The findings show that a T-cell-based therapy alone may not be enough. Researchers must also take into account pancreas cancer's immunosuppressive strategies. "We're trying to get the helpful immune cells into the tumors, and our results show that to do that, we need to get rid of these inhibitory cells the tumors have co-opted," she said.

The team is now working to develop a T-cell therapy to take advantage of their new findings. They plan to test their Gr-MDSC strategy combined with immunotherapy as well as chemotherapy to devise the strongest possible treatment for pancreas cancer.

"Our goal is not incremental advances," Hingorani said. "We want to put as big a hurt on pancreas cancer as possible."

Red cancer-fighting T cells are rare in tumors rich in immunosuppressive cells (left), but rapidly enter tumors when immunosuppressive cells are removed (right).

(Photo Credit: Hingorani Lab, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

Comments