Mimicking that is not possible but researchers have created a seashell with comparable properties and structural complexity. The team led by André Studart, Professor of Complex Materials at ETH Zurich has developed a new procedure that mimics the natural model almost perfectly. The scientists were able to produce a tough, multi-layered material based on the construction principle of teeth or seashells. They managed, for the first time, to re-create in a single complex piece the multiple layers of micro-platelets with identical orientation in each layer.

It is a procedure the ETH researchers call magnetically assisted slip casting (MASC). “The wonderful thing about our new procedure is that it builds on a 100-year-old technique and combines it with modern material research,” says Studart’s doctoral student Tobias Niebel, co-author of a study just published in the specialist journal Nature Materials.

Revival of a 100-year-old technique

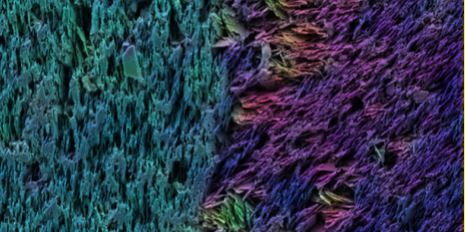

Cross-section of the artificial tooth under an electron microscope (false colour): Ceramic platelets in the enamel are orientated vertically. In the dentin, they are aligned horizontally. Photo: Hortense Le Ferrand/ETH Zürich

This is how MASC works: the researchers first create a plaster cast to serve as a mould. Into this mould, they pour a suspension containing magnetised ceramic platelets, such as aluminium oxide platelets. The pores of the plaster mould slowly absorb the liquid from the suspension, which causes the material to solidify and to harden from the outside in.

The scientists create an ordered layer-like structure by applying a magnetic field during the casting process, changing its orientation at regular intervals. As long as the material remains liquid, the ceramic platelets align to the magnetic field. In the solidified material, the platelets retain their orientation.

Through the composition of the suspension and the direction of the platelets, a continuous process can be used to produce multiple layers with differing material properties in a single object. This creates complex materials that are almost perfect imitations of their natural models, such as nacre or tooth enamel. “Our technique is similar to 3D printing, but 10 times faster and much more cost-effective,” says Florian Bouville, a post-doc with Studart and co-lead author of the study.

To demonstrate the potential of the MASC technique, Studart’s research group produced an artificial tooth with a microstructure that mimics that of a real tooth. The surface of the artificial tooth is as hard and structurally complex as a real tooth enamel, while the layer beneath is tough, just like the dentine of the natural model.

The co-lead author of the study, doctoral student Hortense Le Ferrand, and her colleagues began by creating a plaster cast of a human wisdom tooth. They then filled this mould with a suspension containing aluminium oxide platelets and glass nanoparticles as mortar. Using a magnet, they aligned the platelets perpendicular to the surface of the object. Once the first layer was dry, the scientists poured a second suspension into the same mould. This suspension, however, did not contain glass particles. The aluminium oxide platelets in the second layer were aligned horizontally to the surface of the tooth using the magnet.

This double-layered structure was then ‘fired’ at 1,600 degrees to densify and harden the material: the term sintering is used for this process. Finally, the researchers filled the pores that remained after the sintering with a synthetic monomer used in dentistry, which subsequently polymerised.

Artificial teeth behave just like real teeth

The researchers are very happy with the result. “The profile of hardness and toughness obtained from the artificial tooth corresponds exactly with that of a natural tooth,” says a pleased Studart. The procedure and the resulting material lend themselves for applications in dentistry.

However, as Studart points out, the current study is just an initial proof-of-concept, which shows that the natural fine structure of a tooth can be reproduced in the laboratory. “The appearance of the material has to be significantly improved before it can be used for dental prostheses.” Nonetheless, as Studart explains, the artificial tooth clearly shows that a degree of control over the microstructure of a composite material can be achieved, which previously was only accessible by living organisms. One part of the MASC process, the magnetisation and orientation of the ceramic platelets, has already been patented.

However, the new production process for such complex biomimetic materials also has other potential applications. For instance, copper platelets could be used in place of aluminium oxide platelets, which would allow the use of such materials in electronics. “The base substances and the orientation of the platelets can be combined as required, which rapidly and easily makes a wide range of different material types with varying properties feasible,” says Studart.

Comments