Researchers supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) nanoscale interdisciplinary research team award and three Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers at Cornell University, Penn State University and Northwestern University recently added ferroelectric capability to material used in common computer transistors, a feat scientists tried to achieve for more than half a century.

Ferroelectric materials provide low-power, high-efficiency electronic memory. Smart cards use the technology to instantly reveal and update stored information when waved before a reader. A computer with this capability could instantly provide information and other data to the user.

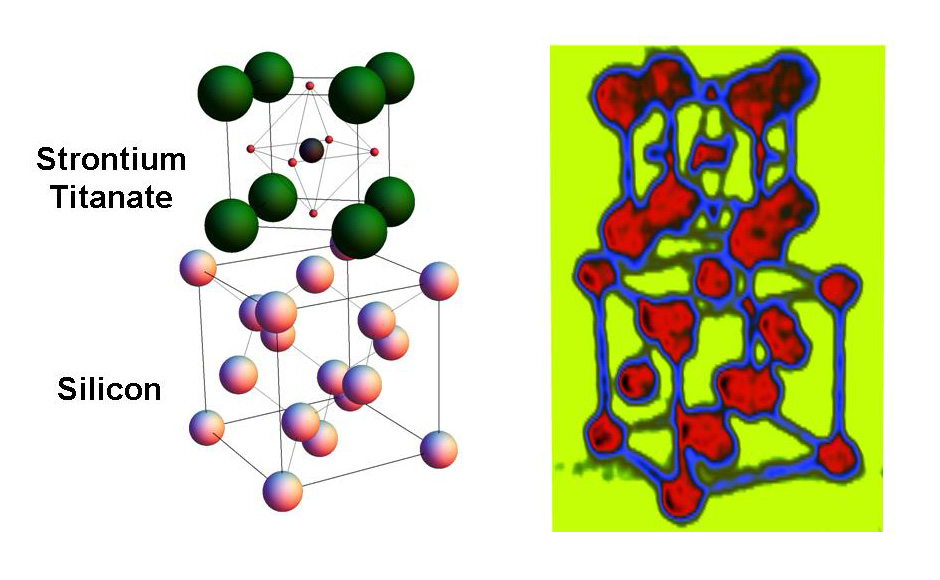

Researchers report matching the spacing of silicon atoms--the principal component of computer semiconductors--and the spacing of atoms in a material called strontium titanate--a normally non-ferroelectric variant of a material used in "instant memory smart cards." The matched spacing allows the silicon to squeeze the strontium titanate in such a way that it produces ferroelectric properities. Ferroelectric materials provide low-power, high-efficiency electronic memory for devices such as "smart cards" that can instantly reveal and update stored information when waved before a reader. When applied to computer transistors, these materials could allow "instant-on" capability, eliminating the time-consuming booting and rebooting of computer operating systems. Credit: Jeremy Levy, University of Pittsburgh

Researchers led by Cornell University materials scientist Darrell Schlom took strontium titanate, a normally non-ferroelectric variant of the ferroelectric material used in smart cards, and deposited it on silicon--the principal component of most semiconductors and integrated circuits--in such a way that the silicon squeezed it into a ferroelectric state.

"It's great to see fundamental research on ordered layering of materials, or epitaxial growth, under strained conditions pay off in such a practical manner, particularly as it relates to ultra-thin ferroelectrics" said Lynnette Madsen, the NSF program director responsible for the Nanoscale Interdisciplinary Research Team award.

The result could pave the way for a next-generation of memory devices that are lower power, higher speed and more convenient to use. For everyday computer users, it could mean no more waiting for the operating system to come online or to access memory slowly from the hard drive.

"Several hybrid transistors have been proposed specifically with ferroelectrics in mind," said Schlom. "By creating a ferroelectric directly on silicon, we are bringing this possibility closer to realization."

More research is needed to achieve a ferroelectric transistor that would make "instant on" computing a reality, but having the materials in direct contact, free of intervening reaction layers, is an important step.

The paper's first author, Maitri P. Warusawithana, is a postdoctoral associate in Schlom's lab. The research team also includes scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Motorola Corp., Ames Laboratory and Intel Corp. They reported their findings in the April 17 Science.

Along with NSF, the Office of Naval Research and the Department of Energy funded the research.

Comments