Hevelius described it as nova sub capite Cygni — a new star below the head of the Swan — and now it is officially known it by the name Nova Vulpeculae 1670. It lies within the boundaries of the modern constellation of Vulpecula (The Fox), just across the border from Cygnus (The Swan) and is also referred to as Nova Vul 1670 and CK Vulpeculae, its designation as a variable star.

Historical accounts of novae are rare and Nova Vul 1670 is both the oldest recorded nova and the faintest nova when later recovered.

Except a new study says it wasn't a nova at all, it was a much rarer, violent breed of stellar collision. It had to be spectacular because it was easily seen with the naked eye during its first outburst, but the traces it left were so faint that only careful analysis using submillimeter telescopes has been able to unravel the mystery.

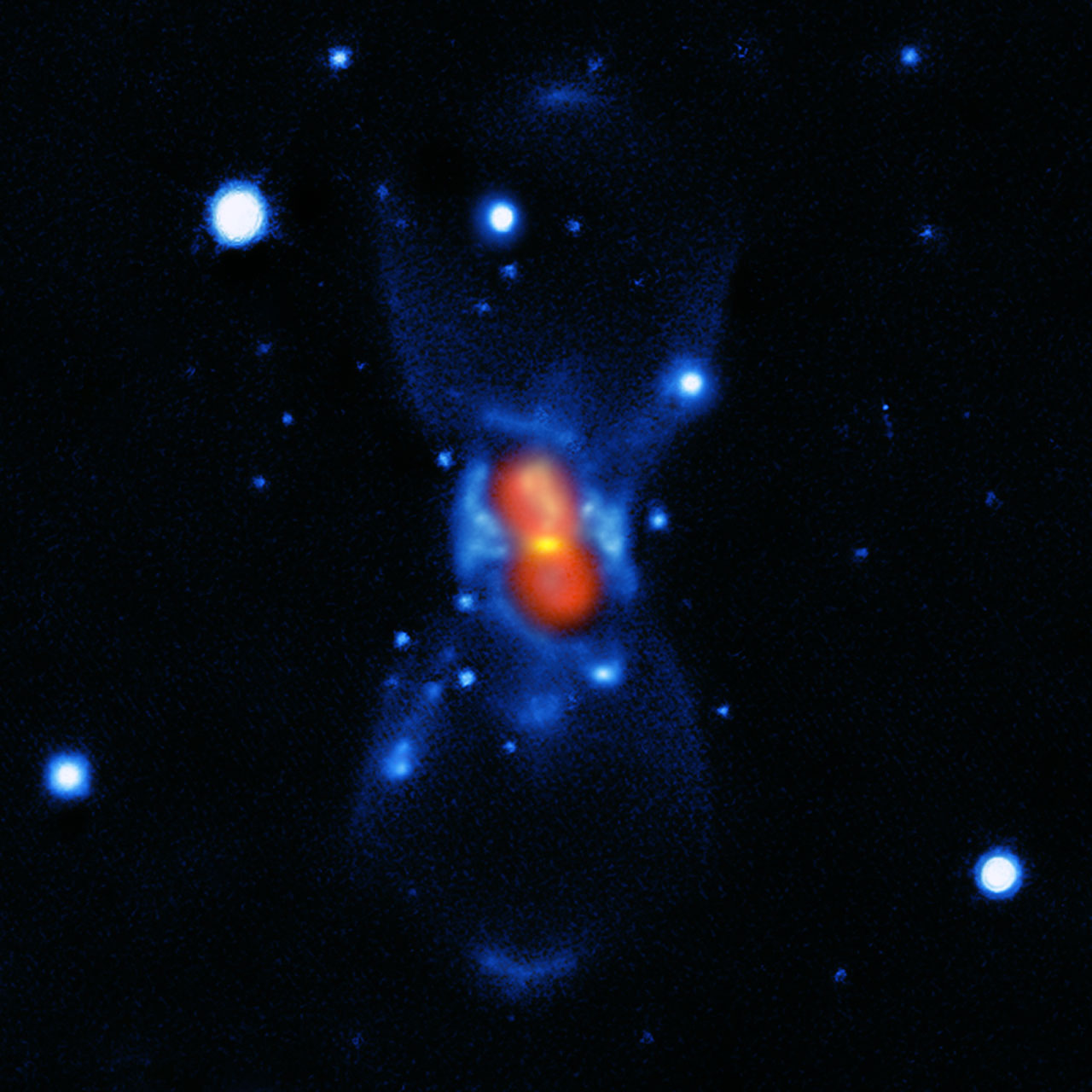

This picture shows the remains of the new star that was seen in the year 1670. It was created from a combination of visible-light images from the Gemini telescope (blue), a submillimetre map showing the dust from the SMA (green) and finally a map of the molecular emission from APEX and the SMA (red). Credit:ESO/T. Kamiński

When it first appeared, Nova Vul 1670 was easily visible with the naked eye and varied in brightness over the course of two years. It then disappeared and reappeared twice before vanishing for good. Although well documented for its time, astronomers of the day lacked the equipment needed to solve the riddle of the apparent nova’s peculiar performance.

During the 20th century, astronomers came to understand that most novae could be explained by the runaway explosive behavior of close binary stars. But Nova Vul 1670 did not fit this model well at all and remained a mystery.

Even with ever-increasing telescopic power, the event was believed to have left no trace, and it was not until the 1980s that a team of astronomers detected a faint nebula surrounding the suspected location of what was left of the star. While these observations offered a link to the sighting of 1670, they failed to shed any new light on the true nature of the event witnessed over the skies of Europe over three hundred years ago.

“We have now probed the area with submillimeter and radio wavelengths. We have found that the surroundings of the remnant are bathed in a cool gas rich in molecules, with a very unusual chemical composition,” says lead author Tomasz Kamiński of ESO and the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn.

Using APEX, the Submillimeter Array (SMA) and the Effelsberg radio telescopes, they discovered the chemical composition and measure the ratios of different isotopes in the gas. Together, this created an extremely detailed account of the makeup of the area, which allowed an evaluation of where this material might have come from.

What the team discovered was that the mass of the cool material was too great to be the product of a nova explosion, and in addition the isotope ratios the team measured around Nova Vul 1670 were different to those expected from a nova. But if it wasn’t a nova, then what was it?

The answer is a spectacular collision between two stars, more brilliant than a nova, but less so than a supernova, which produces something called a red transient. These are a very rare events in which stars explode due to a merger with another star, spewing material from the stellar interiors into space, eventually leaving behind only a faint remnant embedded in a cool environment, rich in molecules and dust. This newly recognized class of eruptive stars fits the profile of Nova Vul 1670 almost exactly.

Citation: T. Kamiński et al., “Nuclear ashes and outflow in the oldest known eruptive star Nova Vul 1670”, Nature 23 March 2015

Comments