The International Peanut Genome Initiative, a multinational group crop geneticists who have been working in tandem for the last several years, have successfully sequenced the genome of

Arachis hypogaea

- the peanut.

Arachis hypogaea and also called groundnut and, of course, peanut, is important both commercially and nutritionally. While the oil- and protein-rich legume is seen as a cash crop in the developed world, it remains a valuable sustenance crop in developing nations. The new peanut genome sequence is available to researchers and plant breeders across the globe to aid in the breeding of more productive and more resilient peanut varieties.

The peanut in fields today is the result of a combination of two wild species, Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, which occurred in north Argentina between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago. Because its ancestors were two different species, today's peanut is a polyploid, meaning the species can carry two separate genomes, designated A and B subgenomes.

The genome sequence assemblies and additional information are available at http://peanutbase.org/files/genomes/.

The effort to sequence the peanut genome has been underway for several years. While peanuts were successfully bred for intensive cultivation for thousands of years, relatively little was known about the legume's genetic structure because of its complexity, according to Peggy Ozias-Akins, a plant geneticist with the IPGI and is director of the University of Georgia Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Genomics.

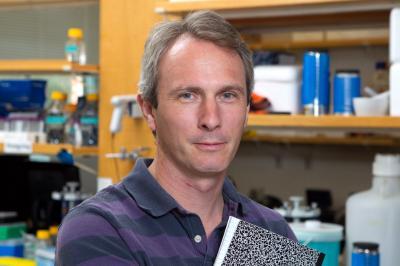

Scott Jackson, director of the University of Georgia Center for Applied Genetic Technologies in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, serves as chair of the International Peanut Genome Initiative, or IPGI and said, "The peanut crop is important in the United States, but it's very important for developing nations as well. In many areas, it is a primary calorie source for families and a cash crop for farmers."

Globally, farmers tend about 24 million hectares of peanuts each year and produce about 40 million metric tons.

"Improving peanut varieties to be more drought-, insect- and disease-resistant can help farmers in developed nations produce more peanuts with fewer pesticides and other chemicals and help farmers in developing nations feed their families and build more secure livelihoods," said plant geneticist Rajeev Varshney of the International Crops Research Institute for Semi-Arid Tropics in India, who serves on the IPGI.

"Until now, we've bred peanuts relatively blindly, as compared to other crops," said IPGI plant geneticist David Bertioli of the Universidade de Brasília. "We've had less information to work with than we do with many crops, which have been more thoroughly researched and understood."

Scott Jackson, chair of the International Peanut Genome Initiative. Credit: Paul Efland/UGA

To map the peanut's structure, researchers sequenced the genomes of the two ancestral parents because together they represent the cultivated peanut. The sequences provide researchers access to 96 percent of all peanut genes in their genomic context, providing the molecular map needed to more quickly breed drought- and disease-resistant, lower-input and higher-yielding varieties of peanuts.

The two ancestor wild species had been collected in nature, conserved in germplasm banks and then used by the IPGI to better understand the peanut genome. The genomes of the two ancestor species provide excellent models for the genome of the cultivated peanut. A. duranenis serves as a model for the A subgenome of the cultivated peanut while A. ipaensis represents the B subgenome.

Knowing the genome sequences of the two parent species will allow researchers to recognize the cultivated peanut's genomic structure by differentiating between the two subgenomes present in the plants. Being able to see the two separate structural elements also will aid future gene marker development—the determination of links between a gene's presence and a physical characteristic of the plant. Understanding the structure of the peanut's genome will lay the groundwork for new varieties with traits like added disease resistance and drought tolerance.

In addition, these genome sequences will serve as a guide for the assembly of the cultivated peanut genome that will help to decipher genomic changes that led to peanut domestication, which was marked by increases in seed number and size.

In the U.S. peanuts are a major row crop throughout the South and Southeast. While they are a major economic driver for the U.S. economy, the legume is also crucial to the diets and livelihoods of millions of small farmers in Asia and Africa, many of whom are women.

Apart from being a rich source of oil (44 percent to 55 percent), protein (20 percent to 50 percent) and carbohydrates (10 percent to 20 percent), peanut seeds are an important nutritional source of niacin, folate, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, iron, riboflavin, thiamine and vitamin E.

"While the sequencing of the peanut can be seen as a great leap forward in plant genetics and genomics, it also has the potential to be a large step forward for stabilizing agriculture in developing countries," said Dave Hoisington, program director for the U.S. Agency for International Development Feed the Future Peanut and Mycotoxin Innovation Lab, which is hosted at UGA.

"With the release of the peanut genome sequence, researchers will now have much better tools available to accelerate the development of new peanut varieties with improved yields and better nutrition," he said.

Comments