Carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere is absorbed into ocean waters, where it dissolves and lowers the pH of the water. Acidic waters affect fish behavior by disrupting a specific receptor in the nervous system, called GABAA, which is present in most marine organisms with a nervous system. When GABAA stops working, neurons stop firing properly.

Dixson's previous research has shown that fish living on coral reefs where carbon dioxide seeps from the ocean floor were less able to detect predator odor than fish from normal coral reefs. Study co-author Philip Munday, from James Cook University in Australia, has shown in previous work that a tiny coral reef predator fish, the dottyback, also loses interest in food in waters that simulate ocean acidification conditions forecast for the future.

In the experimental part of the new study, conducted at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, 24 sharks from local waters were studied in a 10-meter-long flume. The flume resembled two lanes of a swimming pool. Odor from a squid was pumped down one lane of the flume, while normal seawater was pumped down the other side.

Sharks tend to prefer one side of a tank over the other, so researchers first assessed each sharks' side preference. Then the research team ran control experiments under normal ocean conditions to ensure that the sharks were tracking the food cue. Under present-day water conditions, sharks adjusted their position in the flume to spend a greater amount of time on the side containing the squid odor plume, regardless of the individual shark's natural side preference.

Next, sharks spent five days in holding pools of three different carbon dioxide concentrations: local water concentration today (405 ± 26 microatmospheres (µatms) CO2), projected midcentury concentration (741 ± 22 µatms CO2), projected concentration for 2100 (1,064 ± 17 µatms CO2). Sharks were not fed while in the holding pools to ensure they were motivated to track a food odor. The sharks were then released into the flume and their tracking behavior was observed.

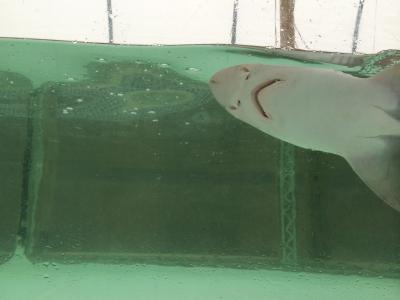

A smooth dogfish shark attacks an odor cue at at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

(Photo Credit: Jayne M. Gardiner, J Exp Biol, 2007)

Sharks from the normal seawater pool and mid-level carbon dioxide pool spent more than 60 percent of their time in the water stream containing the food stimulus. Sharks from the high carbon dioxide pool spent less than 15 percent of their time in the water stream containing the food stimulus. These sharks avoided the odor plume even when it was on the side of the flume that the sharks' naturally prefer.

The food odor stream was pumped through bricks to make the plume flow better and to give the sharks a target to attack. Sharks treated under mid and high CO2 conditions also reduced their attack behavior.

"They significantly reduced their bumps and bites on the bricks compared to the control group," Dixson said. "It's like they're uninterested in their food."

Exposure to carbon dioxide did not significantly affect the sharks' overall activity levels. The gill rate of the sharks – an indicator of heart rate – held in different water conditions was not significantly different, suggesting that differences in stress to the sharks was not likely affecting the experimental results.

Dixson noted that the study was carried out under laboratory conditions and thus does not allow for the full evaluation of the potential effects of ocean acidification on predatory abilities of the smooth dogfish.

Live food was not used as the odor cue because sharks can detect prey with their other senses, such as hearing and their ability to detect electrical impulses. By using an odor cue, the researchers were focusing on only the chemical sensing of sharks. Dixson's future work will explore how sharks' other senses might be affected by ocean acidification.

Sharks are an ancient species, and in the past have adapted to ocean acidification conditions projected for the future. But they've never had to adapt to changes happening as quickly as they are today.

"It's the rate of change that's happening that's concerning. Sharks have never had to deal with it this fast," Dixson said.

A smooth dogfish swims in a flume at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts. Arrows point to the brick baffles and the source of the food odor plume. The start box holding area is also labeled. Dashed lines indicate the flume quadrants used to determine activity level through number of lines crossed.

(Photo Credit: Danielle Dixson)

The new study is the first time that sharks' ability to sense the odor of their food has been tested under conditions that simulate the acidity levels expected in the oceans by the turn of the century.

(Photo Credit: Danielle Dixson)

Comments