It also suggests a broader definition of what counts as synthetic life.

Study co-author Kevin Kit Parker previously demonstrated bioengineered constructs that can grip, pump, and even walk. He says the inspiration to mimic a jellyfish came out of frustration with the state of the cardiac field. Similar to the way a human heart moves blood throughout the body, jellyfish propel themselves through the water by pumping. In figuring out how to take apart and then rebuild the primary motor function of a jellyfish, the goal was to figure out how such pumps really worked.

"It occurred to me in 2007 that we might have failed to understand the fundamental laws of muscular pumps," says Parker, Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics at the Harvard School of Engineering. "I started looking at marine organisms that pump to survive. Then I saw a jellyfish at the New England Aquarium and I immediately noted both similarities and differences between how the jellyfish and the human heart pump."

To build the Medusoid (cool name, right?) lead author Janna Nawroth, a doctoral student in biology at Caltech teamed with Parker and Nawroth's adviser, John Dabiri, a professor of aeronautics and bioengineering at Caltech and expert in biological propulsion. It turned out that jellyfish, believed to be the oldest multi-organ animals in the world, were an ideal subject, as they use muscles to pump their way through water, and their basic morphology is similar to that of a beating human heart.

To reverse engineer a medusa jellyfish, they used analysis tools borrowed from the fields of law enforcement biometrics and crystallography to make maps of the alignment of subcellular protein networks within all of the muscle cells within the animal. They then conducted studies to understand the electrophysiological triggering of jellyfish propulsion and the biomechanics of the propulsive stroke itself.

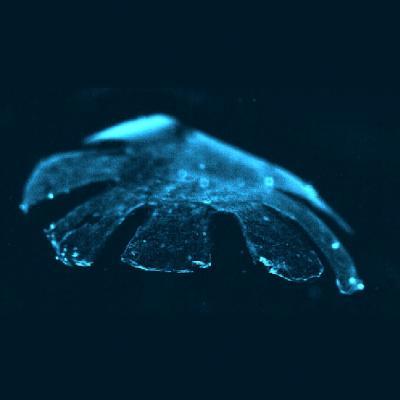

Medusoid. Artificial jellyfish. Credit: Harvard and Caltech

Based on such understanding, it turned out that a sheet of cultured rat heart muscle tissue that would contract when electrically stimulated in a liquid environment was the perfect raw material to create an ersatz jellyfish. The team then incorporated a silicone polymer that fashions the body of the artificial creature into a thin membrane that resembles a small jellyfish, with eight arm-like appendages.

Using the same analysis tools, the investigators were able to quantitatively match the subcellular, cellular, and supracellular architecture of the jellyfish musculature with the rat heart muscle cells.

Medusoid in action.

"A big goal of our study was to advance tissue engineering," says Nawroth. "In many ways, it is still a very qualitative art, with people trying to copy a tissue or organ just based on what they think is important or what they see as the major components—without necessarily understanding if those components are relevant to the desired function or without analyzing first how different materials could be used."

The artificial construct was placed in container of ocean-like salt water and shocked into swimming with synchronized muscle contractions that mimic those of real jellyfish. (In fact, the muscle cells started to contract a bit on their own even before the electrical current was applied.)

"I was surprised that with relatively few components—a silicone base and cells that we arranged—we were able to reproduce some pretty complex swimming and feeding behaviors that you see in biological jellyfish," says Dabiri.

Their design strategy, they say, will be broadly applicable to the reverse engineering of muscular organs in humans.

the Medusoid construct.jpeg)

Parallel frame capture of the swimming behavior of a real jellyfish(top) compared to (bottom) the Medusoid construct. Credit: Harvard

"As engineers, we are very comfortable with building things out of steel, copper, concrete," says Parker. "I think of cells as another kind of building substrate, but we need rigorous quantitative design specs to move tissue engineering to a reproducible type of engineering. The jellyfish provides a design algorithm for reverse engineering an organ's function and developing quantitative design and performance specifications. We can complete the full exercise of the engineer's design process: design, build, and test."

In addition to advancing the field of tissue engineering, Parker adds that he took on the challenge of building a creature to challenge the traditional view of synthetic biology which is "focused on genetic manipulations of cells." Instead of building just a cell, he sought to "build a beast."

Looking forward, the researchers aim to further evolve the artificial jellyfish, allowing it to turn and move in a particular direction, and even incorporating a simple "brain" so it can respond to its environment and replicate more advanced behaviors like heading toward a light source and seeking energy or food.

Along with Parker, Nawroth, and Dabiri, contributors to the study included Hyungsuk Lee, Adam W. Feinberg, Crystal M. Ripplinger, Megan L. McCain, and Anna Grosberg, all at Harvard.

Published in Nature Biotechnology.

Comments