Like with many things, a lot of variables go into evolution. Some is luck, some is necessity, some is circumstance. Over time, for example, a region of blacksmiths will grow bigger arms. It isn't an epigenetic or Lamarckian evolution event but it will happen over generations because holding a hammer becomes important in that circumstance.

Almost anything can claim an evolutionary basis, if you try hard enough. In the run up to the last American presidential election, there were even claims that people were born liberal or conservative. Yes, social psychologists and the political pundits who take them seriously believed the American left and right were evolving differently than the rest of the world.

And so there has been a recurring conjecture that a culture of violence - we may idealize the natural world today but nature mostly kills organisms off - shaped many things about it, including our faces. And our fists. Evolutionary psychologists will like that our mugs were guided by bar fights over women.

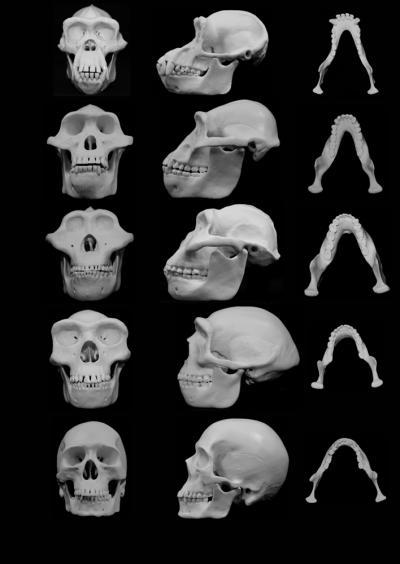

Biologist David Carrier and physician Michael H. Morgan, both from the University of Utah, contend that human faces —especially those of our australopith ancestors — evolved to minimize injury from punches to the face during fights between males. That is dramatically different than the more Occam's Razor idea that that facial evolution of our early ancestors resulted largely from the need to chew hard-to-crush foods such as nuts.

University of Utah biologist David Carrier and Michael H. Morgan, a University of Utah physician, contend that human faces -- especially those of our australopith ancestors -- evolved to minimize injury from punches to the face during fights between males. Their research is published in the June 9 issue of Biological Reviews. Courtesy image/University of Utah

"The australopiths were characterized by a suite of traits that may have improved fighting ability, including hand proportions that allow formation of a fist; effectively turning the delicate musculoskeletal system of the hand into a club effective for striking," said Carrier, lead author of the study. "If indeed the evolution of our hand proportions were associated with selection for fighting behavior you might expect the primary target, the face, to have undergone evolution to better protect it from injury when punched."

The rationale for the research conclusions came from determining a number of different elements, said Carrier.

"When modern humans fight hand-to-hand the face is usually the primary target. What we found was that the bones that suffer the highest rates of fracture in fights are the same parts of the skull that exhibited the greatest increase in robusticity during the evolution of basal hominins. These bones are also the parts of the skull that show the greatest difference between males and females in both australopiths and humans. In other words, male and female faces are different because the parts of the skull that break in fights are bigger in males," said Carrier.

"Importantly, these facial features appear in the fossil record at approximately the same time that our ancestors evolved hand proportions that allow the formation of a fist. Together these observations suggest that many of the facial features that characterize early hominins may have evolved to protect the face from injury during fighting with fists," he said.

The latest study by Carrier and Morgan builds on their previous work, which indicate that violence played a greater role in human evolution than is generally accepted by many anthropologists.

In recent years, Carrier has investigated the short legs of great apes, the habitual bipedal posture of hominins, and the hand proportions of hominins. He's currently working on a study on foot posture of great apes that also relates to evolution and fighting ability.

Research on the evolution of creatures in the genus Australopithecus - immediate predecessors of the human genus Homo —remains relevant today as scientists continue to look for clues into how and why humans evolved into who they are now from predecessors who inhabited the earth about 4 to 5 million years ago.

Carrier said his newly published research in Biological Reviews both "provides an alternative explanation for the evolution of the hominin face" but also "addresses the debate over whether or not our distant past was violent."

"The debate over whether or not there is a dark side to human nature goes back to the French philosopher Rousseau who argued that before civilization humans were noble savages; that civilization actually corrupted humans and made us more violent. This idea remains strong in the social sciences and in recent decades has been supported by a handful of outspoken evolutionary biologists and anthropologists. Many other evolutionary biologists, however, find evidence that our distant past was not peaceful," said Carrier.

"The hypothesis that our early ancestors were aggressive could be falsified if we found that the anatomical characters that distinguish us from other primates did not improve fighting ability. What our research has been showing is that many of the anatomical characters of great apes and our ancestors, the early hominins (such as bipedal posture, the proportions of our hands and the shape of our faces) do, in fact, improve fighting performance," he said.

Morgan added the new study brings interesting elements to the ongoing conversation about the role of violence in evolution.

"I think our science is sound and fills some longstanding gaps in the existing theories of why the musculoskeletal structures of our faces developed the way they did," said Morgan.

"Our research is about peace. We seek to explore, understand, and confront humankind's violent and aggressive tendencies. Peace begins with ourselves and is ultimately achieved through disciplined self-analysis and an understanding of where we've come from as a species. Through our research we hope to look ourselves in the mirror and begin the difficult work of changing ourselves for the better."

Comments