Inventor and AC electricity proponent Nikola Tesla was on a mission to transmit energy through thin air almost a century ago, but, claims about a conspiracy to keep his work quiet aside, experimental attempts at the feat have resulted in cumbersome devices that only work over very small distances.

The Toyota Research Institute of North America and Duke University have demonstrated the feasibility of wireless power transfer using metamaterials to create a "superlens" that focuses low-frequency magnetic fields over distances much larger than the size of the transmitter and receiver. The superlens translates the magnetic field emanating from one power coil onto its twin nearly a foot away, inducing an electric current in the receiving coil.

The experiment was the first time such a scheme has successfully sent power through the air with an efficiency many times greater than what could be achieved with the same setup minus the superlens.

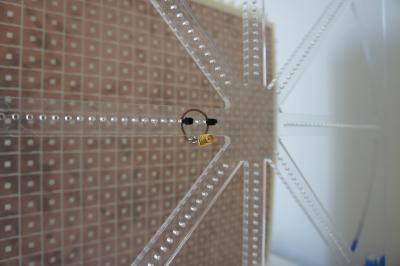

This small copper coil created the electromagnetic field by running an alternating electric current through it. In the background is the metamaterial "superlens" that focused the electromagnetic field onto another identically sized copper coil on the other side, which greatly increased the wireless transfer's power. Courtesy of Guy Lipworth and Joshua Ensworth, graduate student researchers at Duke University

"For the first time we have demonstrated that the efficiency of magneto-inductive wireless power transfer can be enhanced over distances many times larger than the size of the receiver and transmitter," said Yaroslav Urzhumov, assistant research professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke University. "This is important because if this technology is to become a part of everyday life, it must conform to the dimensions of today's pocket-sized mobile electronics."

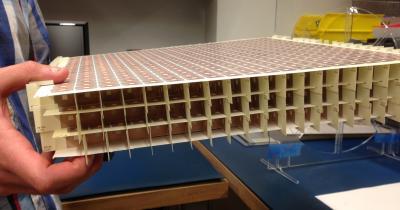

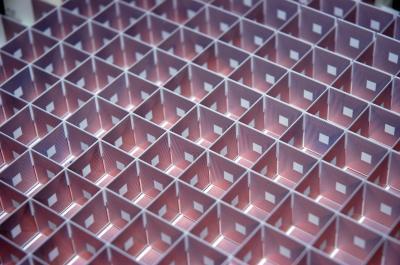

In the experiment, the team created a square superlens, which looks like a few dozen giant Rubik's cubes stacked together. Both the exterior and interior walls of the hollow blocks are intricately etched with a spiraling copper wire reminiscent of a microchip. The geometry of the coils and their repetitive nature form a metamaterial that interacts with magnetic fields in such a way that the fields are transmitted and confined into a narrow cone in which the power intensity is much higher.

On one side of the superlens, the researchers placed a small copper coil with an alternating electric current running through it, which creates a magnetic field around the coil. That field, however, drops in intensity and power transfer efficiency extremely quickly, the further away it gets.

"If your electromagnet is one inch in diameter, you get almost no power just three inches away," said Urzhumov. "You only get about 0.1 percent of what's inside the coil." But with the superlens in place, he explained, the magnetic field is focused nearly a foot away with enough strength to induce noticeable electric current in an identically sized receiver coil.

Urzhumov noted that metamaterial-enhanced wireless power demonstrations have been made before at a research laboratory of Mitsubishi Electric, but with one important caveat: the distance the power was transmitted was roughly the same as the diameter of the power coils. In such a setup, the coils would have to be quite large to work over any appreciable distance.

A side view of the metamaterial "superlens." Both its width and thickness affects how far it can boost the wireless transfer of power using electromagnetic fields. Courtesy of Duke University

"It's actually easy to increase the power transfer distance by simply increasing the size of the coils," explained Urzhumov. "That quickly becomes impractical, because of space limitations in any realistic scenario. We want to be able to use small-size sources and/or receivers, and that's what the superlens enables us to do."

Urzhumov said magnetic fields have distinct advantages over the use of electric fields for wireless power transfer.

"Most materials don't absorb magnetic fields very much, making them much safer than electric fields," he said. "In fact, the FCC approves the use of 3-Tesla magnetic fields for medical imaging, which are absolutely enormous relative to what we might need for powering consumer electronics. The technology is being designed with this increased safety in mind."

Each side of each constituent cube of the "superlens" is set with a long, spiraling copper coil. The end of each coil is connected to its twin on the reverse side of the wall. Courtesy of Guy Lipworth, graduate student researcher at Duke University

Going forward, Urzhumov wants to drastically upgrade the system to make it more suitable for realistic power transfer scenarios, such as charging mobile devices as they move around in a room. He plans to build a dynamically tunable superlens, which can control the direction of its focused power cone.

"The true functionality that consumers want and expect from a useful wireless power system is the ability to charge a device wherever it is – not simply to charge it without a cable," said Urzhumov. "Previous commercial products like the PowerMat™ have not become a standard solution exactly for that reason; they lock the user to a certain area or region where transmission works, which, in effect, puts invisible strings on the device and hence on the user. It is those strings -- not just the wires -- that we want to get rid of."

Comments