Are you smarter than a pigeon? We don't mean smarter as in able to figure out why it's $14 a day for lousy internet access in a hotel or $14 to see an old movie in your hotel room or the hospitality industry's general preference for the number 14, we mean practical social smarts, like meeting the opposite sex. Animals have "social smarts" too, it turns out, with a range of behaviors that can enhance species survival, according to studies being presented here in Chicago at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting.

Evolution shouldn't leave out social behavior, it seems.

Neandertals were the closest relatives of currently living humans. They lived in Europe and parts of Asia until they became extinct about 30,000 years ago. For more than a hundred years, paleontologists and anthropologists have been striving to uncover their evolutionary relationship to modern humans.

A multi-institutional team of researchers has reported the sequences for all of the 99 known strains of cold virus, nature's most ubiquitous human pathogen. The feat exposes, in precise detail, all of the molecular features of the many variations of the virus responsible for the common cold, the inescapable ailment that makes us all sneeze, cough and sniffle with regularity.

Conducted by teams at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the J. Craig Venter Institute, the work to sequence and analyze the cold virus genomes lays a foundation for understanding the virus, its evolution and three-dimensional structure and, most importantly, for exposing vulnerabilities that could lead to the first effective cold remedies.

Scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill say they have helped develop a new genomic test that can help clinicians predict which breast cancer patients are most likely to survive the disease and which treatments may be most effective in increasing those chances of survival.

By specifically measuring the activity level of a small subset of the 20,000 plus genes that may be “turned on” or “turned off” within each tumor, this genomic test can give patients a more accurate picture of how their disease might progress.

Not sure who to date? Garth Sundem answers it in

The Valentine's Day Man-O-Meter. Be sure to take it as gospel because he never just makes stuff up.

If you're still unsure who to pursue, you may be looking in the wrong places. This study says

We Want To Date People Slightly More Attractive Than We Are. How, then, does anyone get a date? It's another mystery of love.

One of the weaknesses of using a surname as a guide in understanding genetic characteristcs has been the belief that 1 in 10 births were the result of infidelity - so the name is not only an incorrect characteristic but could even be deceptive.

Not, so, says a study funded by the Wellcome Trust published this week in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, which may help genealogists create more accurate family trees even when records are missing. It suggests that the often quoted "one in ten" figure for children born through infidelity is unlikely to be true.

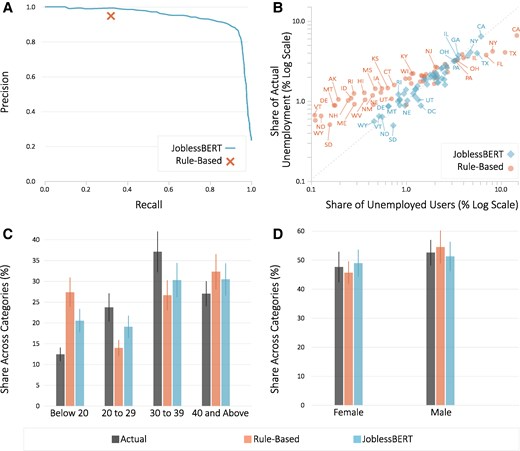

Social Media Is A Faster Source For Unemployment Data Than Government

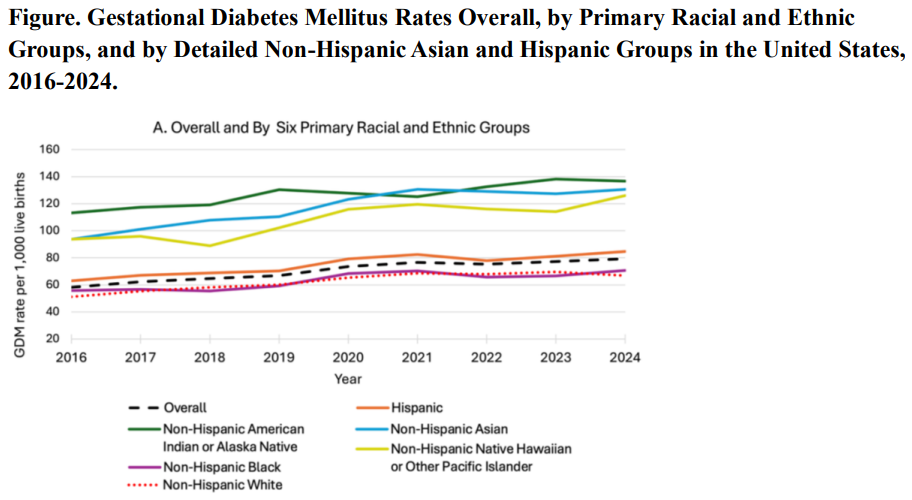

Social Media Is A Faster Source For Unemployment Data Than Government Gestational Diabetes Up 36% In The Last Decade - But Black Women Are Healthiest

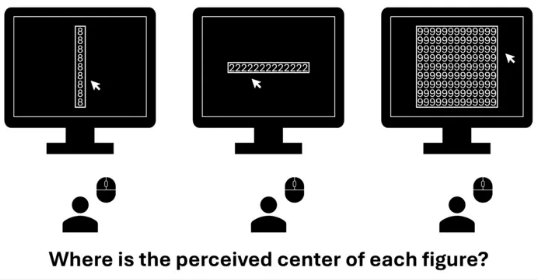

Gestational Diabetes Up 36% In The Last Decade - But Black Women Are Healthiest Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive Spaces

Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive Spaces Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For Food

Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For Food