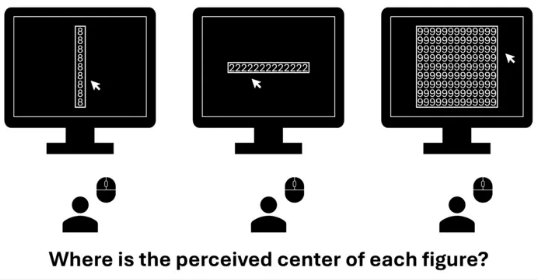

Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive Spaces

Object-Based Processing: Numbers Confuse How We Perceive SpacesResearchers recently studied the relationship between numerical information in our vision, and...

Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For Food

Males Are Genetically Wired To Beg Females For FoodBees have the reputation of being incredibly organized and spending their days making sure our...

The Scorched Cherry Twig And Other Christmas Miracles Get A Science Look

The Scorched Cherry Twig And Other Christmas Miracles Get A Science LookBleeding hosts and stigmatizations are the best-known medieval miracles but less known ones, like ...

$0.50 Pantoprazole For Stomach Bleeding In ICU Patients Could Save Families Thousands Of Dollars

$0.50 Pantoprazole For Stomach Bleeding In ICU Patients Could Save Families Thousands Of DollarsThe inexpensive medication pantoprazole prevents potentially serious stomach bleeding in critically...