Deadly emerging diseases have risen steeply across the world and an international research team has provided the first scientific evidence mapping the outbreaks’ main sources.

They say:

New diseases originating from wild animals in poor nations are the greatest threat to humans and;

Expansion of humans into shrinking pockets of biodiversity and resulting contacts with wildlife are the reason.

Meanwhile, richer nations are nursing other outbreaks, including multidrug-resistant pathogen strains, through overuse of antibiotics, centralized food processing and other technologies.

Emerging diseases—defined as newly identified pathogens, or old ones moving to new regions--have caused devastating outbreaks already. The HIV/AIDS pandemic, thought to have started from human contact with chimps, has led to over 65 million infections; recent outbreaks of SARS originating in Chinese bats have cost up to $100 billion. Outbreaks like the exotic African Ebola virus have been small, but deadly.

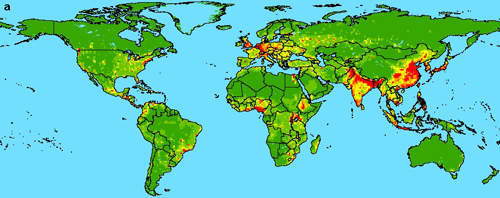

Despite three decades of research, previous attempts to explain these seemingly random emergences were unsuccessful. In the new study, researchers from four institutions analyzed 335 emerging diseases from 1940 to 2004, then converted the results into maps correlated with human population density, population changes, latitude, rainfall and wildlife biodiversity. They showed that disease emergences have roughly quadrupled over the past 50 years. Some 60% of the diseases traveled from animals to humans (such diseases are called zoonoses) and the majority of those came from wild creatures.

With data corrected for lesser surveillance done in poorer countries, “hot spots” jump out in areas spanning sub-Saharan Africa, India and China; smaller spots appear in Europe, and North and South America.

“We are crowding wildlife into ever-smaller areas, and human population is increasing,” said coauthor Marc Levy, a global-change expert at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), an affiliate of Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “The meeting of these two things is a recipe for something crossing over.”

The main sources are mammals. Some pathogens may be picked up by hunting or accidental contact; others, such as Malaysia’s Nipah virus, go from wildlife to livestock, then to people. Humans have evolved no resistance to zoonoses, so the diseases can be extraordinarily lethal.

The scientists say that the more wild species in an area, the more pathogen varieties they may harbor. Kate E. Jones, an evolutionary biologist at the Zoological Society of London and first author of the study, said the work urgently highlights the need to prevent further intrusion into areas of high biodiversity. “It turns out that conservation may be an important means of preventing new diseases,” she said.

About 20 percent of known emergences are multidrug-resistant strains of previously known pathogens, including tuberculosis. Richer nations’ increasing reliance on modern antibiotics has helped breed such dangerous strains, said Peter Daszak, an emerging-diseases biologist with the Consortium for Conservation Medicine at the Wildlife Trust, another Earth Institute affiliate, who directed the study. Daszak said that some strains, such as lethal variants of the common bacteria e. coli, now spread widely with great speed because products like raw vegetables are processed in huge, centralized facilities. “Disease can be a cost of development,” he said.

The group’s analyses showed also that more diseases emerged in the 1980s than any other decade—likely due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which led to other new diseases in immune-compromised victims. In the 1990s, insect-transmitted diseases saw a peak, possibly in reaction to rapid climate changes that started taking hold then. Team members soon hope to study this possibility and its future implications.

Daszak says the study has immediate uses. “The world’s public-health resources are misallocated,” he said. “Most are focused on richer countries that can afford surveillance, but most of the hotspots are in developing countries. If you look at the high-impact diseases of the future, we’re missing the point.” Team members say nations must share more technology and resources in hotspots to reduce risk. “We need to start finding pathogens before they emerge,” said Daszak.

The study appears in the Feb. 21 issue of Nature. In addition to the ZSL and Earth Institute researchers, the study was coauthored by John L. Gittleman, dean of the Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia.

Comments