It's obvious that that those working in healthcare roles are at heightened risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 and therefore COVID-19, but it has not been clear what the risks might be compared to those working in other sectors.

For a new paper, severe infection was defined as a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, while in hospital, or death attributable to the virus. It drew on linked data from the UK Biobank study (2006-10), a long term study tracking the factors potentially influencing the development of disease in around half a million middle and older age adults, COVID-19 test results from Public Health England, and recorded deaths for the period 16 March to 26 July 2020 and found that healthcare workers are 7 times as likely to have severe COVID-19 infection than 'non-essential' workers while those with jobs in the social care and transport sectors are twice as likely to do so.

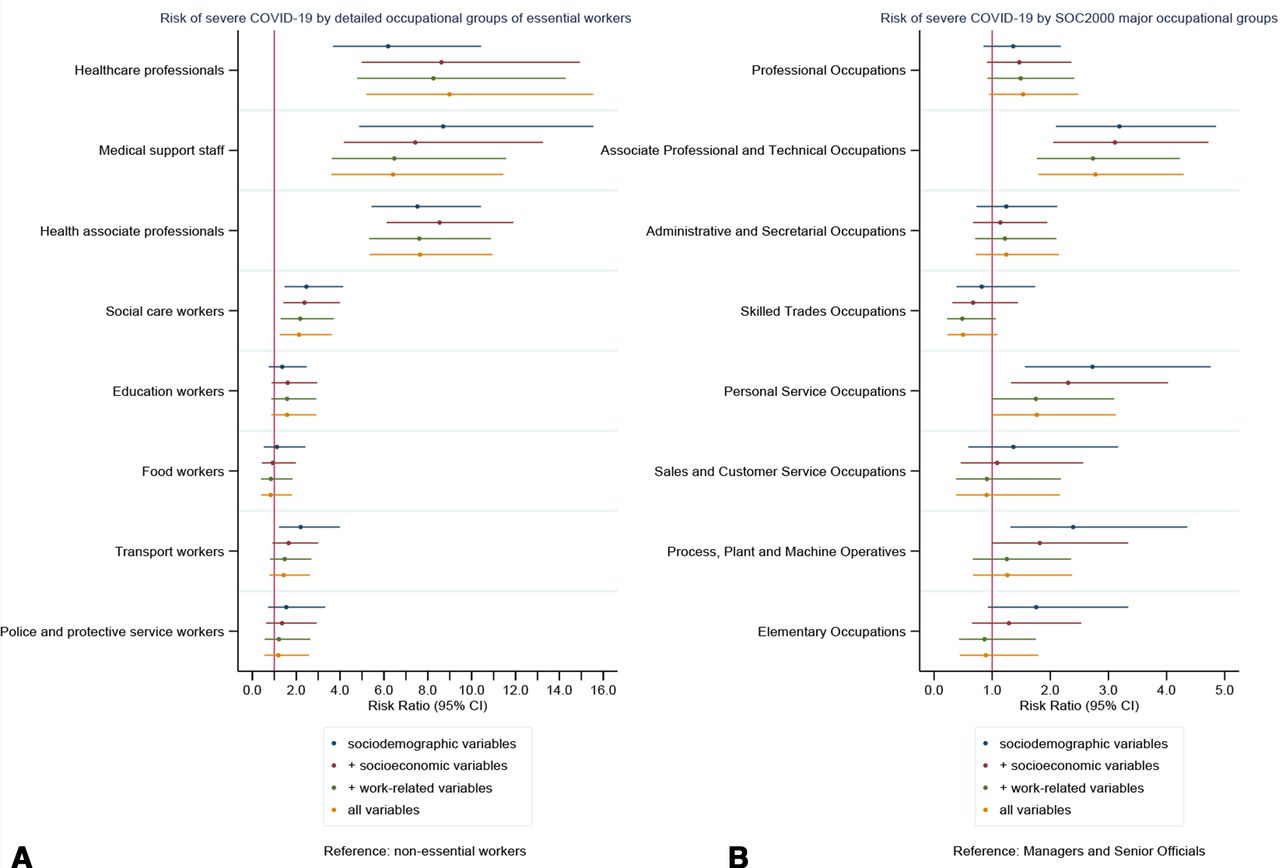

Risk ratios for the associations between (A) detailed essential occupational groups, and (B) SOC 2000 major occupational groups and severe COVID-19. SOC, Standard Occupation Classification.

There are limitations, especially when it comes to drawing a line between disease prevalence and income. This is an observational study, and can't establish cause. It is in the exploratory section of epidemiology and science would have to determine if the links are anything more than statistical because initial background data were collected more 10-14 years ago and incapable of accounting for any changes in health, lifestyle, income and employment status. The UK Biobank is also not representative of the broader population nor were the researchers able to take account of the changes in risk over time, such as the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE).

The study included 120,075 employees aged 49-64. Of these, 35,127 (29%) were classified as essential workers: healthcare (9%); social care and education (11%); 'other' to include police and those working in transport and food preparation (9%). Those of Black and Asian ethnicities comprised nearly 3% each of the total. They were more likely to be essential workers, as were women.

In all, 271 employees had severe COVID-19 infection. Healthcare professionals, defined as doctors and pharmacists; medical support staff; health associate professionals, defined as nurses and paramedics; and social care and transport workers had higher rates of severe COVID-19 than non-essential workers.

Compared with non-essential workers, those working in healthcare roles were more than 7 times as likely to have severe infection. And those working in social care and in education were 84% as likely to do so; while 'other' essential workers had a 60% higher risk of developing severe COVID-19.

When the researchers refined the employment categories further, it emerged that medical support staff were nearly 9 times as likely to develop severe disease; those in social care almost 2.5 times as likely to do so; while transport workers were twice as likely to do so. And when the researchers looked at the impact of ethnicity, they found that the risks of severe infection for Black and Asian non-essential workers were similar to those for white essential workers, suggesting that ethnicity is a key factor.

Non-essential workers of Black and Asian backgrounds were also more than 3 times as likely to develop severe COVID-19 infection as white non-essential workers, while Black and Asian essential workers were more than 8 times as likely to do so.

With the exception of transport workers, for whom heightened risk of severe COVID-19 infection was linked to socioeconomic status, the findings held true even after accounting for potentially influential risk factors, including lifestyle, co-existing health problems, and work patterns.

Comments