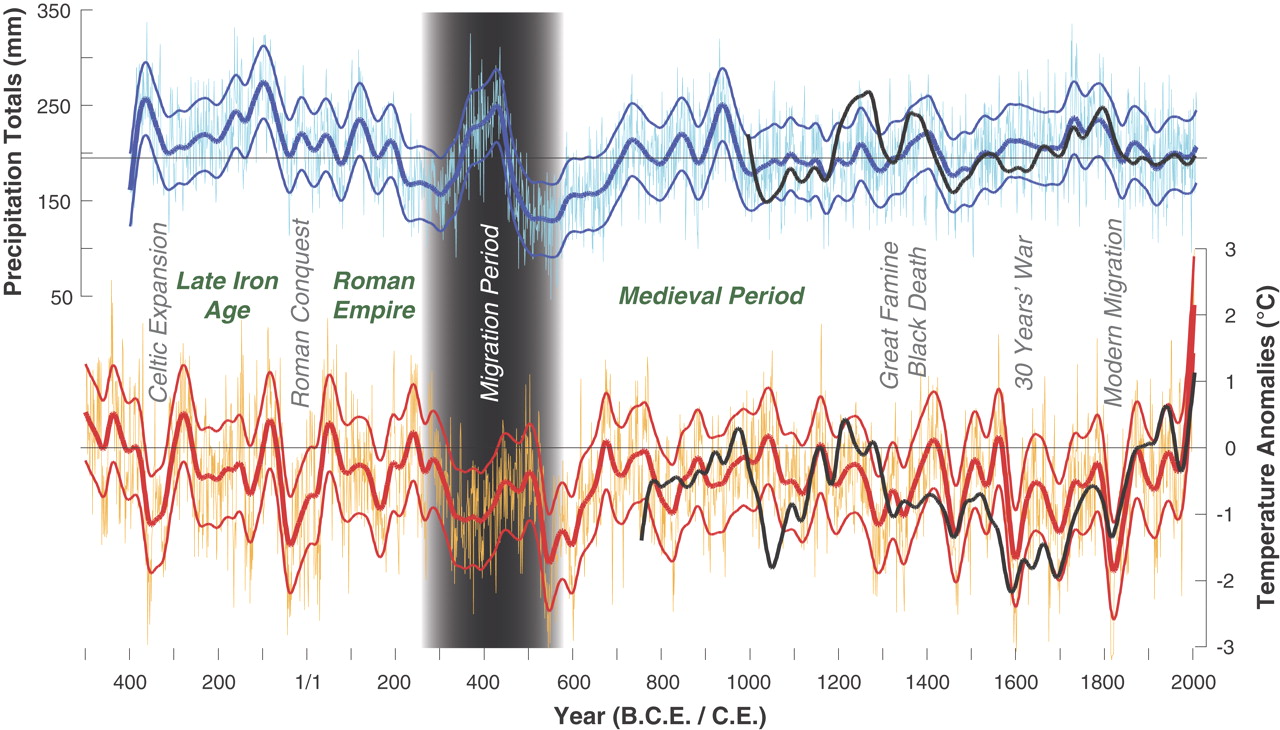

A new study in Science uses the same techniques as dendrochronology to map the rise and fall of empires and cultures as it was recorded in tree rings - and then to weather conditions.

Obviously this requires some calibration, which is as much art as science. They took weather records from the past 200 years (I know, I know, sketchy for all but the last 40 years, but that is why I say it is tricky) and then mapped those temperatures to still-living trees and examined how temperature and moisture affected tree-ring growth.

Then, armed with that sort of decoder ring they went back in time, looking at wood in old buildings or otherwise preserved. They call the results 'precise' and that is not accurate but it sure is interesting - and the results are precise assuming the baselines they created are accurate, but there is no way to prove that.

The results, they tell Andew Curry at Science, show results like warm, wet summers ideal for agriculture mapping to prosperity and long-term droughts that match the timing of barbarian invasions while colder, wetter weather coincided with the plague that devastated Europe in 1347.

More accurately than trying to blame weather for the fall of Rome, though, is that it gave them a rough measure of human activity. During good times, more trees were cut down for building and fuel, leaving behind more samples, while during bad times the wood samples are few.

So even the absence of data can tell us something about the conditions of the time.

Citation: Ulf Büntgen, Willy Tegel, Kurt Nicolussi, Michael McCormick, David Frank, Valerie Trouet, Jed O. Kaplan, Franz Herzig, Karl-Uwe Heussner, Heinz Wanner, Jürg Luterbacher and Jan Esper, '2500 Years of European Climate Variability and Human Susceptibility', Science DOI: 10.1126/science.1197175

Comments