I first became interested in genome size because of its tie-ins with important evolutionary questions in which I was (and still am) interested, such as punctuated vs. gradual patterns, levels of selection, and adaptive vs. non-adaptive processes.

What I didn't realize was that one component of the question, the quantity of DNA that is non-functional (but not necessarily inconsequential) with regard to the phenotype of the organism, is such a hot-button issue. I had vague inklings at first that young-earth creationists would object to the idea of non-functional DNA -- because God, as they say, don't make no junk. (Why intelligent design proponents, who purport to take a strictly scientific view of the question, also assume that non-coding DNA cannot be non-functional remains unstated).

And of course there has always been a persistent undertone in biology that non-coding DNA must be doing something or it would have been deleted. This latter view, which derives directly from a hardcore adaptationist approach, destroys the argument by creationists that "Darwinism" has prevented researchers from considering functions for non-coding DNA.

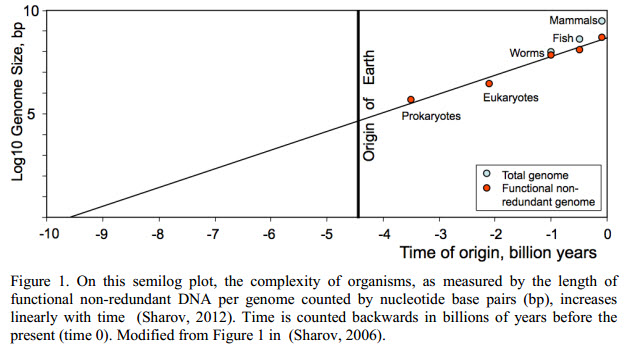

Moore’s Law, The Origin Of Life, And Dropping Turkeys Off A Building

Moore’s Law, The Origin Of Life, And Dropping Turkeys Off A Building Genome Reduction In Bladderworts Vs. Leg Loss In Snakes

Genome Reduction In Bladderworts Vs. Leg Loss In Snakes Another Just-So Story, This Time About Fists

Another Just-So Story, This Time About Fists