Reference letters are meant to be an important input for academic selections, because they provide first-hand information on the previous experience of the candidates, from scholars who are supposed to be authoritative enough to be trusted, and unconcerned enough to provide a unbiased assessment.

In many cases the above suppositions turn out to be problematic, to say the least; for sure they are so in my case, anyway. Their main problem is the human factor: it is very difficult to be completely honest if you see the students as more than just a last name and a first name, or a University ID number. That is possible when you give exam scores for students who attended your course, because you did not really get to know them. But not with ones you worked with.

In about thirty years of activity as an experimental particle physicist, I have supervised over 40 pre-Ph.D. students, and I have interacted with some 60 more enough to be able to assess their competences rather precisely. Assuming I were asked to write a reference letter for each of these 100 students, I believe I could maybe manage to write a completely unbiased letter for 20 or 30 of them.

Why can't I detach myself enough to provide a balanced assessment of the worth of these young researchers? Because in interacting with them I do not just get to know and appraise their competences - I also get exposed to the rest of their personality, where they came from, what struggles they faced during their studies. All of that comes with the package, so to speak.

I share a bit of my life with each of them, one way or the other; we work together, I teach them things, I correct their writeups, suggest changes to their presentations, advise them in a number of ways; but we also occasionally travel together (to conferences or workshops), share office space, sometimes have dinner together (especially during common travel). In other words, we have what may be called a social interaction, and this is less hierarchical than it probably ought to be, because of my general attitude and dislike of hierarchies. I do not want my students to feel that there is any barrier among us: we are on the same level, scientists of different age doing research together! I encourage them to speak to me in an informal way, and always try to put them at ease.

A declared bias

So whenever one of these fellows asks me to write in support of his or her next career move, I often can't bring myself to kill their chances. I do not think I have ever written in a letter that a candidate is below average, for example. And I do declare it - my top-10% assessments happen significantly more often than 10% of the time.

Not to worry - a recalibration of this sort of systematic bias in the inputs we offer to our peer in reference letters is routinely done by anybody who is used to read them; the system would now work otherwise. What this means is that academics know one another, at least indirectly, and they are capable of reading between the lines. After a little while, colleagues of A and B understand that A is known to always try to sell their students as the next Einstein, while B has been flagged as one that assesses with "he's good" truly exceptional candidates. A debiasing puts things back in order.

If we consider what other data in addition to reference letters does a selection committee for Ph.D. candidates have, to provide a meaningful ranking - i.e. if we consider the context more in general - we see that they usually can assess them based on final scores of bachelor and master courses, possibly a few authored publications, conference talks or posters, and sometimes grants won or other prizes received. Do these documents provide enough data to allow for a pre-selection leading to a short list of candidates to directly interview?

One particularly tough case

The answer, of course, is that it depends a lot on the number of candidates! In 2023, the Ph.D. course in Physics at Padova University was offering a record 44 Ph.D. positions. There were over 400 applications, and the selection committee (formed by five members) had the impossible task of creating a meaningful ranking out of the enormous amount of data they had from the candidates.

I was not a member of the committee, but I was privy to internal information because one of the 44 offered grants was for a project I was funding; in addition, one of the five members was my office mate and a long-time colleague in CDF and CMS. So I got to know a bit more about the difficulties the committee faced in that occasion (I did participate and chaired several selection committees in the past, but the number of candidates was usually one order of magnitude smaller, which changes the boundaries of the problem very significantly). It was really a nightmare for them!

If you can allow yourself to interview no more than 80 to 100 candidates - because you have a life!, the problem becomes one of discarding 80% of them just out of the provided documentation. It is very difficult to do so from documents that are sometimes hard to interpret and put in relation to one another - e.g., the evaluation scores in different universities around the world, or the real worth of prizes sometimes claimed by e.g. Indian or Pakistani candidates (some countries provide ranking certificates to the students, but their value is not always very clear).

So, reference letters at least put a face behind claims of the worth of the candidates. And they end up still making a difference. And if my letters push my former students a bit more than they should, well, shoot - I won't complain!

But these are my students!

After all, deep down I have the conviction that having worked with me, these fellows do have some developed skills that others might not possess in the same amount. I try to transmit to my students several things --from physics knowledge (of course) to machine learning tricks (of course), to a basic understanding of statistics to diagonal thinking--, but one of these abilities in particular can make the difference by itself. And the way I transmit it to them is by being an example: the most powerful way I know to teach things. In this particular case it also involves being a bit of an a****le, but it is for a good cause!

The superpower in question is critical, skeptical thinking. Whatever result they show me, during our analysis meetings, I will invariably be questioning it and trying to prove it wrong; or rather, expose my inner thoughts on why I am not convinced by something. Of course, I do it with the most tact I can use... This is a very healthy procedure, which lets you ask the right questions, whose answer will teach you a lot about the system you are studying. I will make an example from the latest graph a student produced for me the other day.

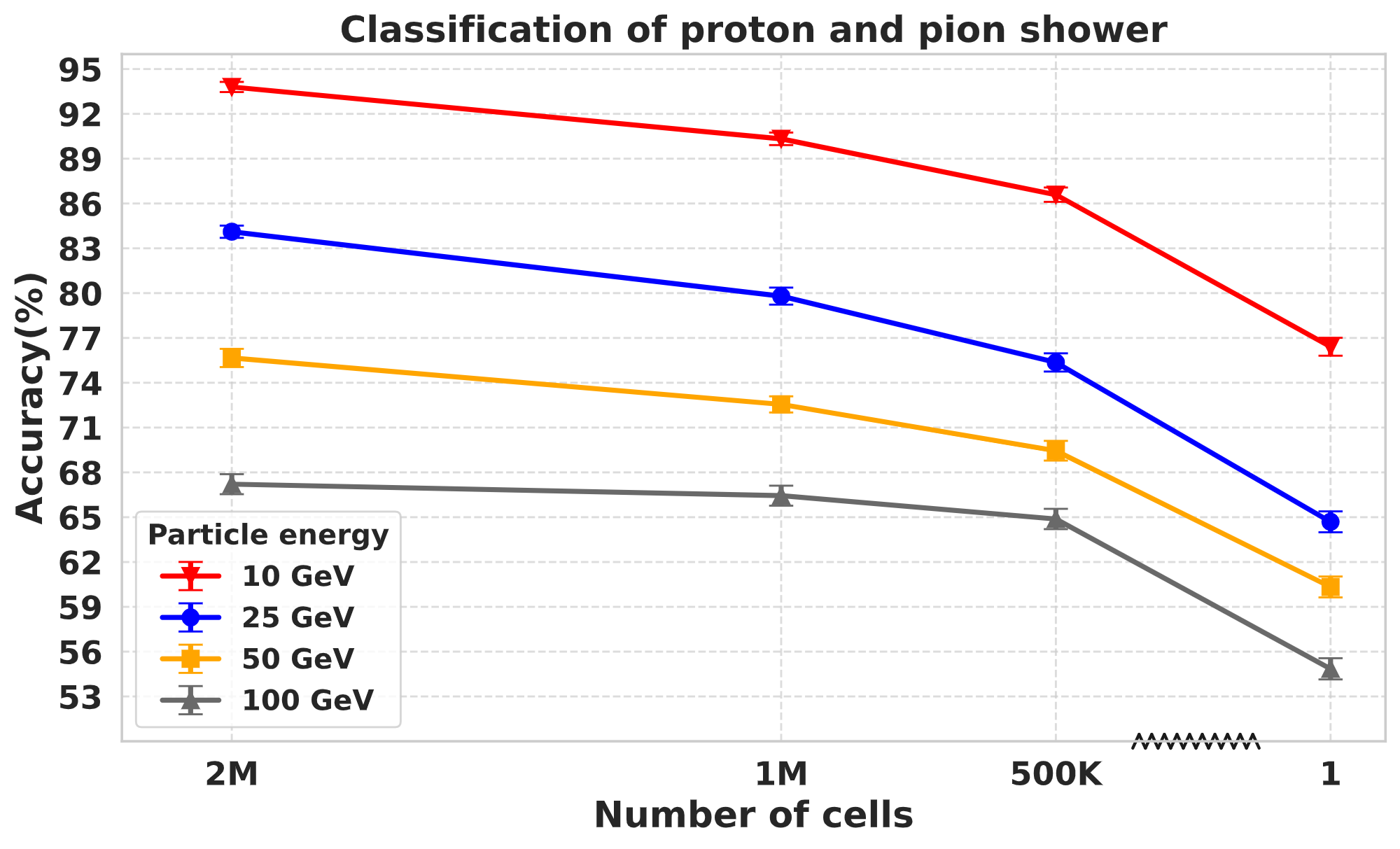

In the figure above (credits go primarily to Abhishek and Andrea de Vita, who are among the authors of a paper we recently published on the matter) you can see the accuracy of discrimination of the signal left by protons from pions of different energies (10,25,50,100 GeV) hitting a highly-segmented calorimeter block made of lead tungstate. The data come from GEANT4 simulations of the apparatus and the physical processes the particles undergo when they shower in the dense material. For context, discriminating hadrons like protons and charged pions based on the topology of their energy deposition pattern in a hadronic shower is something that nobody has ever pulled off convincingly - so the accuracy shown by the four curves may be surprising.

In truth, this graph is the result of over one year of detailed studies, so the results are on solid ground. Yet, I was quite annoying and insisting in questioning how those results were obtained. Was there a bug somewhere? I asked the students who produced it to perform several checks before I accepted the result as genuine, but then I praised them for the achievement! In truth, in a previous instantiation of the work, the outcome of my scepticism was the opposite - it led to discovering a bug that was boosting illegally up the discrimination power. In fundamental physics research, it pays off to be sceptical, as most of the times if something looks too good it is usually wrong!

It is interesting to note that the other day I posted the above graph on Facebook, boasting a bit about the significant accuracy it shows. And I immediately received a couple of skeptical remarks by two Facebook friends who are also colleagues from my experiment. Their respect for my competence did not count in the least in the nature of the exchange: they were adamant in expressing doubts on the genuine nature of the result. I love that! It is exactly this way that science proceeds - you have to beat down the skepticism, as in so doing you can eliminate all possible sources of error, thanks to the shared wisdom.

And by the way: the student who produced the graph above is traveling to the US today, as he recently won a Ph.D. selection... And needless to say, maybe the letter I wrote for him helped!

Comments