Activists unable to get the U.S.federal government to enact any law regarding labeling of genetically modified foods have successfully pushed for their own versions in a handful of states. But the resulting patchwork may create bigger headaches for the food industry.

Oregon’s Secretary of State certified a petition Wednesday to put GMO labeling on the November ballot. A similar effort is also underway in Colorado. Connecticut, Maine and Vermont have all passed GMO labeling laws over the last two years.

Connecticut's and Maine's statutes have“trigger” clauses that prevent them from going into effect unless certain thresholds are met concerning other nearby states passing similar laws. Vermont's law is the only one without a trigger, and it is already the subject of lawsuits by the Grocery Manufacturers Association and others.

Not all GMO labeling efforts have been successful. New York's proposed bill failed to make it past a key committee in the State Assembly in June, killing it for the second year in a row. If it had passed, Connecticut's regulations would have kicked in as well. Both states will likely be off the hook for at least another year.

Nor is Oregon's initiative a foregone conclusion. A similar ballot question in 2002 failed, garnering less than 30 percent of the vote.

Nevertheless, the recent victories for anti-GMO activists at the state level are producing laws that differ because of variations in individual state priorities, dominant interest groups and other factors. That's worrying to agribusinesses and producers, who foresee a labyrinthine network of regulations heading their way.

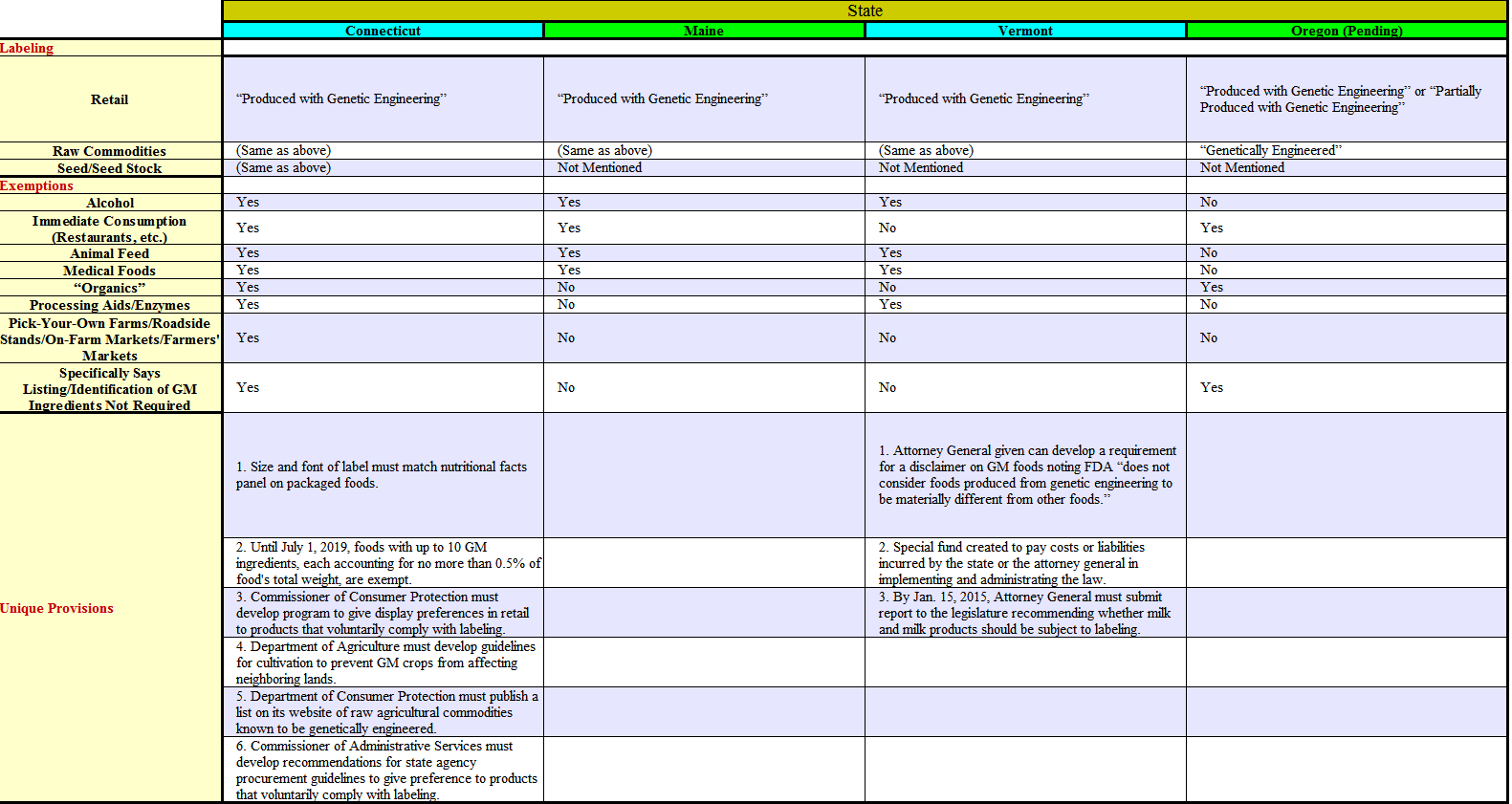

This trouble becomes apparent when contrasting Oregon's initiative and the three extant laws. Connecticut’s - the first to pass - is the most complex. It specifies that the label for packaged food must be in the same size and font as the ingredients in the nutritional facts panel – a level of granularity not matched by the other three states. It is the only that specifically requires labeling of seed and seed stock. It also sets up a requirement for the state to develop a “display preference” system for retail foods that voluntarily comply with the requirements.

At the same time, the Connecticut law provides more exemptions than its counterparts. Most exclude food prepared for immediate consumption (such as in restaurants) and alcohol (though this exemption is notably absent from Oregon’sproposal). But Connecticut also exempts farmer’s markets and roadside stands.

There are other variations as well. Connecticut and Vermont exempt food processing aids and enzymes not intended for consumption; Maine and Oregon do not.

One thing that stands out about Vermont'slegislation is its temporary exemption of milk and milk products, pending a review by that state's Attorney General.

This section of the act has the imprint of history on it. In 1996, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in International Dairy Foods Association v. Amestoy that a Vermont law requiring the labeling of milk products derived from cows given recombinant bovine somatrotropin likely violated the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The “right to know” and strong consumer interest were cited by the court as insufficient to compel speech (in the form of labels) from milk producers. The law was also challenged on the grounds that it violated the Commerce Clause, but the court did not reach that argument before striking the law down.

International Dairy Foods Association v. Amestoy has implications for the Connecticut law and any legislation that should arise in New York: both are under the jurisdiction of the 2nd Circuit. Connecticut’s Office of Legislative Research even noted the case in its analysis of that state’s GMO bill.

In the meantime, a number of companies are shifting their tactics to head off more state action that could further complicate matters. POLITICO obtained a discussion draft in January of a proposal from the Grocery Manufacturers Association to create a national -albeit voluntary – standard and submit to further oversight by the Food and Drug Administration.

It's worth asking, of course, how far any of these labeling laws and proposals will go toward accomplishing the stated goal of anti-GMO proponents: the public's right to know what's in its food.

The answer can be found in a telling provision most of these documents share. Oregon's is typical: “This law shall not be construed to require either the listing or identification of any ingredient or ingredients that were genetically engineered,” it says.

We'll explore the ramifications of this little phrase for the “right to know” argument in a coming post.

Comments