Though 70 percent have poor science literacy, if you ask most how much of their belief system is grounded in science, a lot will say The Science Is On Their Side. It is not, but confirmation bias let them think it is. For example, nutritionists, diet gurus, and wellness influencers prey on those who claim to be science literate. Poor people with little education are far less likely to have the money to buy supplements and foods prepared using increasingly esoteric processes, and a lot more skeptical about online brand influencers selling advice subscriptions. Those who say they are highly educated are swayed by meaningless science-y terms like genomics and epigenetics and probiotics when slapped on packages.(2)

Science journalists should be the first line of defense for the public against charlatans and grifters wrapping themselves in claims of science but I admit my generation let the world down. Generation X journalists will promote nearly every epidemiology claim if it "suggests" some trace chemical is dooming us or that some diet will "increase longevity." It is almost always the case that science journalists will rush to endorse anything that matches their political bias, and the political bias runs deep. We grew up thinking Dan Rather was a journalist, after all.

The next generation should be better. I have a lot more confidence in youth than many do. Every few years when people who claim to care about American youth dump on American youth because our kids don't do well on standardized tests (yet then claim More Money will somehow fix it), I am the guy in USA Today defending young people.(3)

For the most part, that confidence in young people has paid off. Millennials were pretty jaded by the environmental apocalypse in their youth and have called out the $3 billion in environmental groups endorsing useless government recycling programs and now composting, and of course the Democratic party's war on nuclear power while endorsing junk like ethanol.

However, Gen Z may be...well...worrisome.

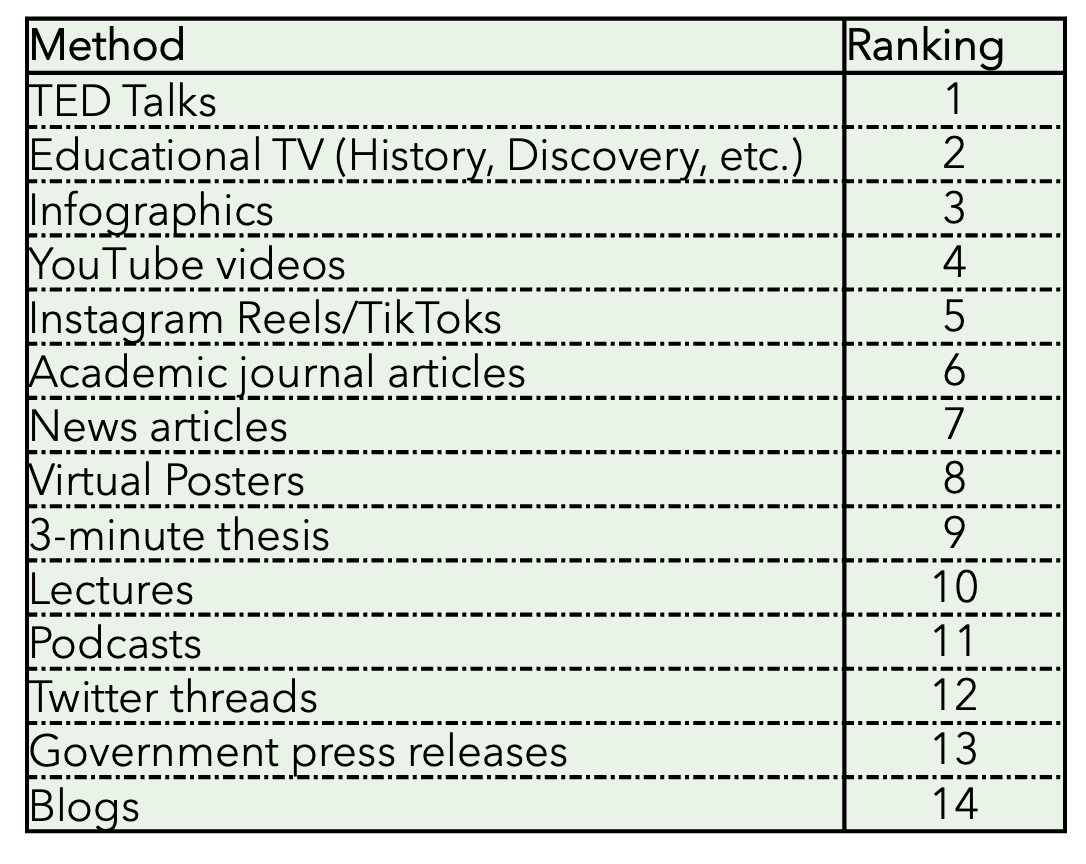

This is just a talking point, it is not representative of Gen Z because it is an informal ranking by a journalism class but a graphic by science communication educator Dr. Casey Hansen shows that those in Gen Z who become journalists may be worse for the public than a chatbot. The graphic Dr. Hansen showed, which forms of science they respected the most, speaks for itself.

One of the reasons for their ranking was "validity of information", and Dr. Hansen seemed proud of that, yet this chart shows the opposite.

When the science communications community sees the validity of this ranking, we see:

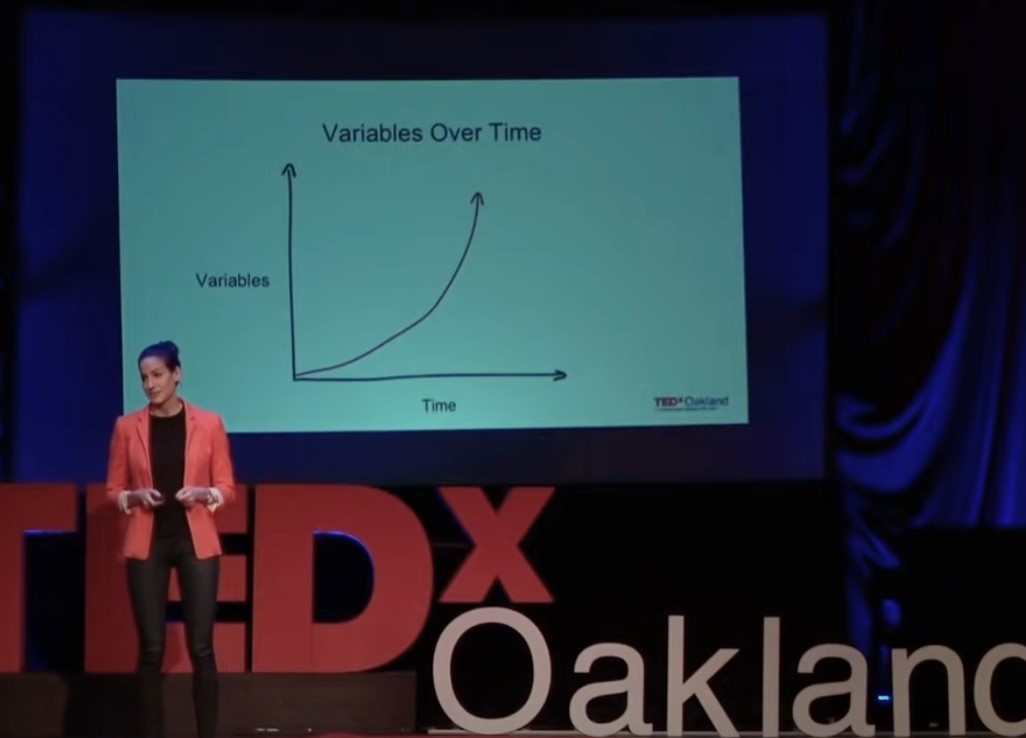

1. TED Talks. They are so bad, and so full of aspirational nonsense, that parodies are everywhere.(4) One person even had a chatbot read a few and then write one, and it read just like an actual TED talk. There is nothing science in 15 minutes of time travel or 'isn't the universe weird?' speculation.

Funny because it's true.

2. Educational TV like Discovery or History Channel.

I could go on but of note and concern is that dead last is science blogs. You know, blogs written by experts like Dr. Tommaso Dorigo without editors or advertisers determining what people get. 300,000,000 people have read articles just at Science 2.0 alone, and I hope everyone felt a little smarter afterward.

Who got smarter after watching a TikTok?(5)

If these students go on to become marcomm people, whatever, but if they go on to be journalists, that is a concern. It will mean they are getting their science in snippets of opinion on Twitter; a corporation in the business of controlling our newsfeeds to get advertising.(6) That is like the Washington Post only getting its information from the New York Times. It makes no sense.

If infographics and press releases created by marketing departments have more credibility to scicomm students than blogs written by actual scientists, how can we expect future journalists to be skeptical enough to know that Environmental Working Group's "dirty dozen" list exempts organic pesticides - the ones made and used by the corporations that donate to EWG - if they rank a Facebook video ahead of agriculture experts?

Am I really, really concerned? Of course not, I didn't understand how the world of science works in school either. I didn't even really understand how much it is instead like Congress until three years after creating Science 2.0. First, this is just a small, interesting sample and I am happy Dr. Hansen shared it. Second, when I talk about American science literacy being number one, I noted 'adult' - a whole lot of people don't develop critical thinking until after college.

Colleges claim they are in the business of fostering discourse and broadening knowledge but few outside the education industry really believe that. There is nothing diverse or welcoming about universities - an Independent Women's Forum speaker just got attacked at San Francisco State University - and handicapped people have more representation on college faculties than Republicans despite them being 44 percent of the population. With insular political selection comes insular thinking in many ways.

*box of corn flakes returns home for winter break after first semester at Bard* Credit: https://twitter.com/NickGreene/status/804829675168022528

Unless you stay in academia, where you can disparage those outside your political tribe because you never have to see them in the hallway, that insular mentality declines. Critical thinking goes way up. As an old saying goes, 'a Republican is a Democrat who got mugged.' Experience makes you more skeptical of stuff even said by your own side.

That noted, and even though political, and therefore intellectual, exclusion on campuses today is far worse than in the past, I still believe that Gen Z will be like other generations, and 30 percent will lead the world in science literacy and we will lead the world in science output and Nobel prizes in the future, just like now.

My only tepid concern is how many true believers of 'press releases are science' silliness will pursue careers in science journalism. If they do, what few jobs are left in the field will instead be better done by ChatGPT.

NOTES:

(1) It sounds impossible but the Chinese demanded that WHO list acupuncture and powdered rhino horns as treatments for COVID-19, so Asia ain't exactly showing any intellectual leadership, while Europe once declared water does not cure thirst and banned sale of ugly fruit - along with any farming process created after 1970. And the standard is reasonable; an understanding of the New York Times Tuesday science section, so low numbers have the feel of truthiness.

(2) NPR doesn't brag about how it educates poor listeners, they brag about how smart and rich their listeners are.

Listeners are affluent, active consumers, business leaders, and involved in their communities. Nearly 70% of all listeners are ages 25-54 with a median age of 42.and

87% more likely to have a bachelor's degree.Unless the average NPR listener is a member of Congress, listeners are so rich that they shouldn't object to being called state-affiliated media on Twitter. Being government-endorsed has been big business in attracting people who like government endorsements of their news coverage.

108% more likely to have an individual employment income of $50,000 or more.

117% more likely to have a household income of $150,000 or more.

152% more likely to have a home valued at $500,000 or more.

(3) Before every science story had to somehow be about Trump, which was the period just before now, where they want it to be a first-person narrative instead of objective or even opinion. Once upon a time, USA Today carried a lot of science, and it was good.

(4)

(5) You're instead lucky your organs haven't already been harvested by the Chinese government.

(6) That said, I like Twitter. I am a nobody despite a legacy blue check (until they take all those away, as announced) but there is freedom in having no one ever read anything. You can throw out harsh opinions and no one minds. I can't do that on Facebook, which actually drives traffic to sites.

Comments