Scientists have created single layers of a naturally occurring rare mineral called tungstenite, or WS2, and the resulting sheet of stacked sulfur and tungsten atoms forms a honeycomb pattern of triangles that have been shown to have unusual light-emitting (photoluminescent) properties.

According to Mauricio Terrones, a professor of physics and of materials science and engineering at Penn State, the triangular structures have potential applications in optical technology; for example, for use in light detectors and lasers.

Terrones explained that creating monolayers -- single, one-atom-thick layers -- is of special interest to scientists because the chemical properties of minerals and other substances are known to change depending on their atomic thickness, opening the door to potentially useful applications of multi-layered materials of various thicknesses. In previous research, scientists had accomplished the feat of making a monolayer of graphene -- a substance similar to the graphite found in pencil leads. "The technique these researchers used was tedious, but it worked," Terrones said. "They basically removed, or exfoliated, the graphene, layer by layer, with Scotch tape, until they got down to a single atom of thickness."

Now, for the first time, Terrones and his team have used a controlled thermal reduction-sulfurization method -- or chemical vapor deposition -- to accomplish the same feat with a rare mineral called tungstenite. The scientists began by depositing tiny crystals of tungsten oxide, which are less than one nanometer in height, and they then passed the crystals through sulfur vapor at 850 degrees Celsius. This process led to individual layers -- or sheets -- composed of one atom in thickness. The resulting structure -- called tungsten disulfide -- is a honeycomb pattern of triangles consisting of tungsten atoms bonded with sulfur atoms.

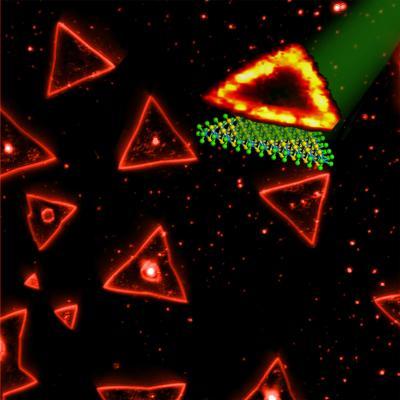

Triangular single layers of tungsten disulfide have been synthesized by Penn State researchers. The edges of the triangles exhibit extraordinary photoluminescence, while the interior area does not. The photoluminescent signal disappears as the number of layers increases. These triangular structures may have potential applications in optical technology; for example, for use in light detectors and lasers. Credit: Terrones lab, Penn State University

"One of the most exciting properties of the tungsten disulfide monolayer is its photoluminescence," Terrones said. Photoluminescence occurs when a substance absorbs light at one wavelength and re-emits that light at a different wavelength. The property of photoluminescence also occurs in certain bioluminescenent animals such as angler fish and fireflies. "One interesting discovery from our work is the fact that we see the strongest photoluminescence at the edges of the triangles, right where the chemistry of the atoms changes, with much less photoluminescence occurring in the center of the triangles," Terrones said. "We also have found that these new monolayers luminesce at room temperature. So no special temperature requirements are needed for the material to exhibit this property."

The researchers also plan to try the chemical-vapor-deposition technology to grow innovative monolayers using other layered materials with potentially useful applications.

Published in NANO Letters

Comments