Where insects bite people there is a risk of bacteria, parasites and other pathogens being transferred. More insects, more risk. Did paint come into popularity for protection it might offer? A new study set out to find if the two were linked, and not just cultural decoration.

“Body-painting began long before humans started to wear clothes. There are archaeological finds that include markings on the walls of caves where Neanderthals lived. They suggest that they had been body-painted with earth pigments such as ochre,” says Susanne Åkesson, who previously claimed that zebra’s stripes act as protection against horseflies. They also contend that pale fur on horses can provide protection over dark fur, and their work won the IgNobel Prize in 2016.

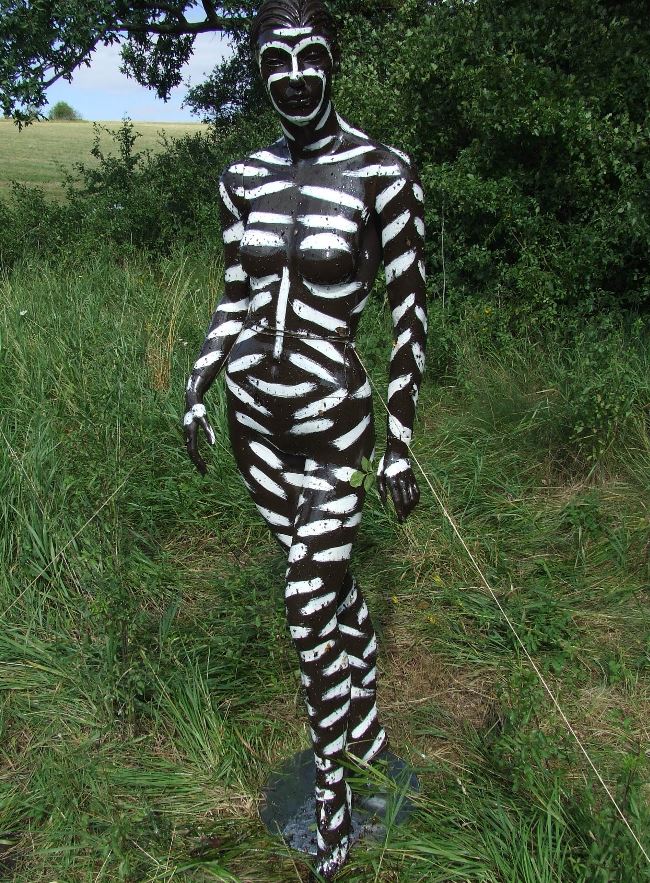

Photo: Gabor Horvath

For a new experiments about humans, the researchers painted three plastic models of humans: one dark, one dark with pale stripes and one beige. They then covered the three models with a layer of insect glue. The dark model attracted ten times more horseflies than the striped model, and the beige model attracted twice as many as the striped one. They also examined whether the attraction of horseflies differed between models that were lying down or standing up. The results show that only females were attracted to the standing models, whereas both males and females were drawn to the supine models.

“These results are in line with previous experiments in which we showed that males gravitate towards water in order to drink and land on surfaces that reflect horizontal, linear polarised light, such as signals from a water surface. Females that bite and suck blood from host animals respond to the same signals as the males, but also to light signals from in the vertical plane, such as the standing models,” concludes Åkesson.

Comments