A recent study focused on one task, language, and finds that to understand language (more specifically, processing spoken sentences), children use both hemispheres. If so, use of both hemispheres may provide the mechanism to compensate after a neural injury. For example, if the left hemisphere is damaged from a perinatal stroke - one that occurs right after birth - a child will learn language using the right hemisphere. A child born with cerebral palsy that damages only one hemisphere can develop needed cognitive abilities in the other hemisphere. In young children, damage to either hemisphere is unlikely to result in language deficits; language can be recovered in many patients even if the left hemisphere is severely damaged.

Yet in almost all adults, sentence processing is possible only in the left hemisphere, according to both brain scanning claims and clinical findings of language loss in patients who suffered a left hemisphere stroke.

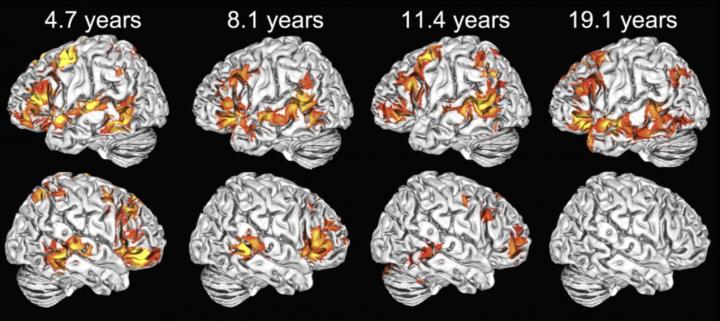

Examples of individual activation maps in each of the age groups. Strong activation in right-hemisphere homologs of the left-hemisphere language areas is evident in the youngest children but then declines with age. Image: Elissa Newport

The conclusions were drawn using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and the pictures lead them to conclude that the adult lateralization pattern is not established in young children and that both hemispheres participate in language during early development.

Brain networks that localize specific tasks to one or the other hemisphere start during childhood but are not complete until a child is about 10 or 11, they say.

The study was small, 39 healthy children, ages 4-13, with 14 adults, ages 18-29, and a series of new analyses of both groups. The participants were given a well-studied sentence comprehension task. The analyses examined fMRI activation patterns in each hemisphere of the individual participants, rather than looking at overall lateralization in group averages. Investigators then compared the language activation maps for four age groups: 4-6, 7-9, 10-13, and 18-29. Penetrance maps revealed the percentage of subjects in each age group with significant language activation in each voxel of each hemisphere. (A voxel is a tiny point in the brain image, like a pixel on a television monitor.) Investigators also performed a whole-brain analysis across all participants to identify brain areas in which language activation was correlated with age.

Researchers found that, at the group level, even young children show left-lateralized language activation. However, a large proportion of the youngest children also show significant activation in the corresponding right-hemisphere areas. (In adults, the corresponding area in the right hemisphere is activated in quite different tasks, for example, processing emotions expressed with the voice. In young children, areas in both hemispheres are each engaged in comprehending the meaning of sentences as well as recognizing the emotional affect.)

Comments