It's generally believed that if you are going to be heavy, pear-shaped (fatter) in the waist and legs) is better than apple (fat around the chest) and a new study validates that holds true for postmenopausal even if they are not heavy and have a normal, healthy body mass index (BMI).

That requires some context. BMI is a fine population-level metric but generally useless for individuals. If you have a high BMI but know you are fit, don't think you need to shed muscle mass to lose weight.

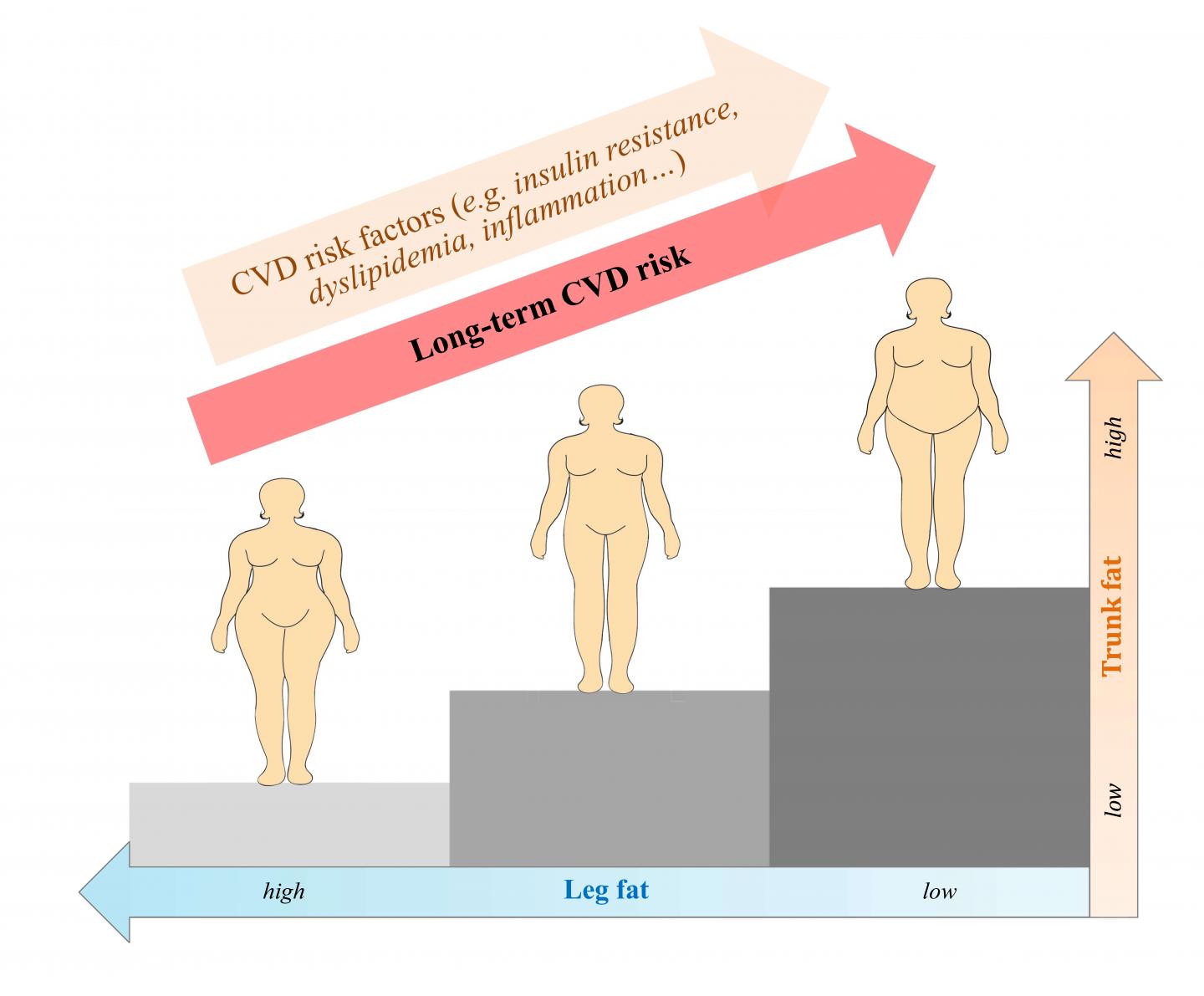

In postmenopausal women, storing a greater proportion of body fat in the legs (pear-shaped) whether having high BMI or not was linked to a significantly decreased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Image: European Society of Cardiology

The authors say this is the first study to look at where fat is stored in the body and its association with risk of CVD in postmenopausal women with normal BMI (18.5 to less than 25 kg/m2). It involved 2,683 women who were part of the Women's Health Initiative in the USA, which recruited nearly 162,000 postmenopausal women between 1993 and 1998 and followed them until February 2017. They did not have CVD at the time of joining the study but, during a median (average) of nearly 18 years of follow-up, 291 CVD cases occurred.

The researchers, led by Dr Qibin Qi, an associate professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, found that women in the top 25% of those who stored most fat round their middle or trunk (apple-shaped) had nearly double the risk of heart problems and stroke when compared to the 25% of women with the least fat stored around their middle. In contrast, the top 25% of women with the greatest proportion of fat stored in their legs had a 40% lower risk of CVD compared with women who stored the least fat in their legs.

Fat distribution matters, even if weight is normal

The researchers found that the highest risk of CVD occurred in women who had the highest percentage of fat around their middle and the lowest percentage of leg fat - they had a more than three-fold increased risk compared to women at the opposite extreme with the least body fat and the most leg fat.

The researchers calculated that, among 1000 women who kept their leg fat constant but reduced the proportion of trunk fat from more than 37% to less than 27%, approximately six CVD cases could be avoided each year, corresponding to 111 cases avoided over the 18 years of the study. Similarly, among 1000 women who kept their trunk fat constant but increased their leg fat from less than 42% to more than 49%, approximately three CVD cases could be avoided each year and 60 cases would have been avoided over the 18-year period.

In addition to overall body weight control, people may also need to pay attention to their regional body fat, even those who have a healthy body weight and normal BMI but participants of our study were postmenopausal women who had relatively higher fat mass in both their trunk and leg regions. Whether the pattern of the associations could be generalizable to younger women and to men who had relatively lower regional body fat remains unknown.

Comments