Machu Picchu is perhaps the most famous archaeological site in the Western Hemisphere. Some social scholars now believe Machu Picchu was a royal estate connected to the lineage of Pachacuti, the emperor credited with establishing the Inca empire. Royals resided at these estates seasonally, but a retinue of slaves (mitmas) and servants (yanacona) did the drudge work in the facilities.

Yet as in Europe and north America, unless you were an elite life was hard and impoverished so being a yanacoma meant more prestige than working in mines or farms - even if they had bee in lands the Inca colonized. For the new study, researchers generated DNA data for 34 individuals buried at Machu Picchu who were believed to be servants of the Inca royal family, as well as 34 individuals from Cusco for comparative purposes.

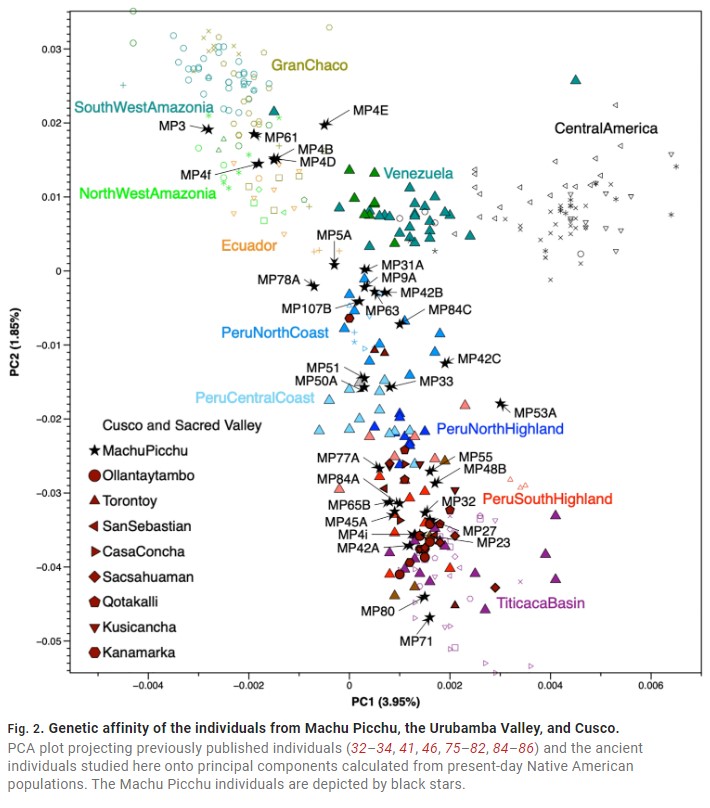

“An unexpected result was the finding that many of the retainers were of Amazonian origin and about a third of them have DNA reflecting significant amounts of Amazonian ancestry,” said lead author Lucy Salazar, a research associate in Yale’s Department of Anthropology. “At least two zones within the Amazonian region are represented.”

Another unexpected result, the scholars said, was that many of the individuals had mixed ancestries, often from regions distant from each other. The researchers said this suggests individuals at Machu Picchu were all the same class once they became servants or slaves. It led to a more diverse population than small agricultural villages.

“This study does not focus on the life of ‘royals’ or political elites, but on the life of those that were brought to Machu Picchu to serve the nobility that lived there and operated the place,” said co-corresponding author Lars Fehren-Schmitz, a professor at UC-SC. “Thus, it gives us a unique insight into the life of a highly diverse community of individuals and their families who were subject to Inca forced relocation and resettlement policies, a group usually referred to as retainers or yanacona.”

Co-corresponding author Jason Nesbitt, associate professor at Tulane, noted that few of the individuals buried at Machu Picchu were from the Inca heartland of the Cuzco Valley or the adjacent Lake Titicaca region. He also said the four cemetery areas at Machu Picchu were not organized by genomic origin. Even the individuals buried in a single burial cave represented diverse genomic backgrounds.

“These results suggest that Machu Picchu was a cosmopolitan community in which people of different backgrounds lived, mated, and were interred together,” Burger said.

Comments