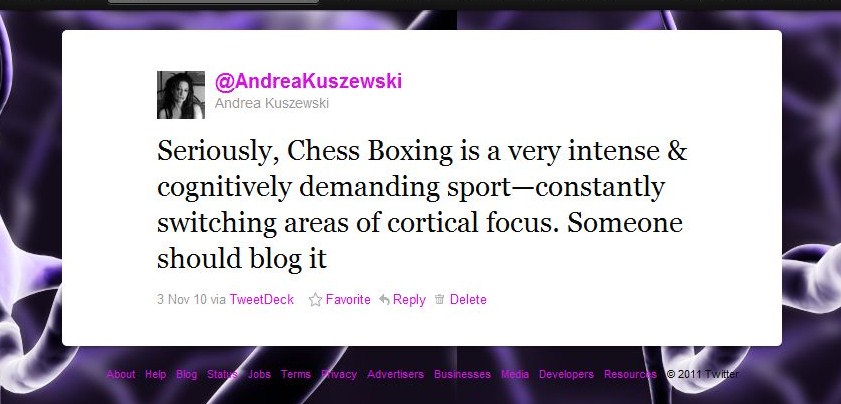

It all started last November with this tweet:

There was a Twitter conversation about politics, and I suggested the candidates decide a winner over a chessboxing match. I had heard about chessboxing a few years prior, but didn't give it much thought, other than marvel at how difficult and unlikely a combo sport it was.

After my tweet, I thought, "Hahahaha... chessboxing... ha... ha—wait a minute. Hmm. It would be wicked hard to be in a ramped up adrenaline state—focusing on proprioception and self-defensive strategies—then immediately switch to a high-demand cognitive activity like chess. Totally different and competing brain areas involved. I wonder what's going on in the brain to allow some people to be very good at the switching back and forth..." So then I suggested someone should blog about it. No one responded. Then I got curious enough to begin looking myself.

I started digging around on the web, searching for literature that explains what is going on in the brain during both facets of the sport: intense physical activity, and intense cognitive activity. I knew that the prefrontal cortex was involved in the cognitive processes necessary for chess, and I knew that a high emotional or arousal state interfered with the ability to effectively problem solve, so the idea of putting these two activities back-to-back was the real challenge. The task-switching intrigued me. So then I began asking myself questions.

Could you train yourself to get better at that? And how would that skill carry over into other daily activities or life situations? Could this help with emotion regulation? And what would be the potential long-term benefits of that skill? Doesn't this all help with resilience, too?

No one had ever looked into this angle of chessboxing, which wasn't too surprising, considering it was a fairly new sport. I spent several days in a rabbit hole investigating cognitive control, emotion regulation, and how those elements were crucial to successful task-switching between the two competing, and very intense, activities.

The more time I spent researching, the more fascinated I was with the neuroscience of the sport. I began to see a narrative emerging. I pitched the idea for an article to Bora Zivkovic, the Blog Editor at Scientific American, and he loved it. My article on chessboxing was published to the Guest Blog on ScientificAmerican.com on January 10th.

Here's an excerpt:

Chess-boxing, a hybrid sport combining chess and boxing, made its first appearance in the pages of a 1992 sci-fi graphic novel by Enki Bilal,Froid Equator, or Cold Equator. Combining what is described as the number-one physical sport and the number-one thinking sport into one completely new hybrid, chess-boxing was meant to be the ultimate test of body and mind.

In 2003, Dutch artist Iepe Rubingh wanted to give that idea life. He saw the potential for an incredibly challenging new sport that would require physical strength and agility, superior problem solving skills, and above all, unbelievable mental discipline and control. No longer just a sci-fi fantasy, chess-boxing is now one of the newest sport fads in Europe, quickly gaining popularity in the U.K. and the U.S.

The most awesome thing about chess-boxing—no, not the sci-fi roots, or the extreme physical skill and mental prowess necessary for dominance—is the brain-changing potential of the sport itself. The specific elements of chess-boxing—the nature of the execution of play as well as the training involved, have some exciting implications for the future of aggression management and preventative treatment of maladaptive behaviors.

The ability to control aggression, emerging from a boxing ring? This may seem unlikely, given that chess-boxing is a contact sport, but let me explain.

(You can read the entire thing here.)

After I had submitted my article and it was slotted for publication, the tragic events of the Arizona shooting unfolded. The idea of emotion regulation and cognitive control training—and how that training could have real-world preventative benefits—suddenly became acutely relevant. I added an addendum to the article to address the shooting incident specifically, emphasizing how critical it was to prevent dysfunctional behaviors before they emerge, instead of running around chasing them with band-aids after they reared their heads. Emotion regulation training was already being explored for its uses as a preventative measure for treating mental illness, but I saw how this same idea could be applied in a more dynamic and fun way—through hybrid-sports such as chessboxing.

The article was a huge hit, and it quickly reached the chessboxing circles. I received emails from both Iepe Rubingh, the Founder of the World Chess Boxing Organisation and first chessboxing champion, and Tim Woolgar, the Founder of the London Chessboxing Club, telling me how much they enjoyed my article and appreciated someone looking into the science and potential psychological benefits of chessboxing. I was wicked stoked to be able to reach the community itself, and to hear such positive feedback.

I exchanged more emails with Tim Woolgar, asking if they had a youth chessboxing program, as I saw real potential for emotion regulation training for kids using this sport. I theorized that it could teach not only emotional stability, but also cognitive control and self-confidence, which in total, add up to an increasingly valuable and important trait: resilience.

A few months later, Tim sent me a link to this video that highlights the Youth Chessboxing program (non-contact, by the way), that he teaches in London:

When I heard Tim speaking in the video about how chessboxing involves controlling emotions, and the other positive social and interpersonal benefits for children training in this sport, I got goosebumps.

The "science of chessboxing"—the theory of emotion regulation and cognitive control training as a preventative treatment for maladaptive behaviors as well as increasing self-confidence and academic performance—is supported by a whole bunch of good data, from psychology to psychopathology to neuroscience. So now I'm thinking: Let's test this theory. Let's take the research from runway to reality. From science blog to the community. There is a group of potential test subjects already out there. Let's collect data!

As I explain in my article:

Combination sports like chess-boxing—ones that involve rapid switching between physical, adrenaline-producing activities, and intense cognitive tasks, are ideal for training in emotion regulation. It may seem that an activity like boxing would promote aggression, but on the contrary—when combined with chess, utilizing short, alternating rounds, there is no time for aggression to build—otherwise you lose the game. If you train kids on how to control their emotional behavior or their aggression before they lash out at another child, then build on those patterns of successful behavior, you are one step ahead of the problem instead of chasing it down. Not to mention, early intervention of any behavior problems almost always means a higher rate of success in the long term.If chessboxing can provide these positive social and psychological benefits, and it can be quantified, then that could mean justification for integrating sports like these into school curricula. Kids are already forced to take gym class, so why not have physical combination sports that can also provide a host of other benefits as well?

And... Why am I telling this story now?

Glad you asked!

I am very pleased to announce that my article, Could Chess-boxing Defuse Aggression in Arizona and Beyond? was just chosen as one of the 50 science articles to be included in this year's publication of The Open Laboratory 2012, an anthology of the year's best science writing on the web. The competition was fierce, so I am very honored to be included in this year's publication.

However, I'm even more excited that this specific article was chosen. Let me explain why.

Wonder and Curiosity

Ed Yong, a fellow science writer, had asked me back in January how I ever thought to write about chessboxing. There was no press release about the 'Science of Chessboxing'. There was no study, no sport-specific evidence for me to summarize and report on. That's not what led to this article. This is what I told him:

It all came out of wonder and curiosity. I was curious about chessboxing. I wondered about the science behind it. It was a puzzle, and I wanted to figure it out. And once I did, I wanted to share it with as many people as possible. I didn't hoard my ideas until they could be published in an academic journal, I wanted to get them out to the public as quickly as I could. And when these brand-new concepts that I had discovered reached the ears of actual people that could benefit from this information, I thought...this is why I write about science. To make these real connections—to facilitate action out of theory. For me, the joy comes not just from bringing scientific knowledge to the public, but in seeing the direct real-world impact that knowledge can have on individual people—perhaps making their lives a little bit better—all because I took a chance on a scientific curiosity. For me, this is what being a scientist is all about.

Comments