On the 17th of June 2008, The Richard Green Library, a collection of rare scientific books was put up for bid by Christi’s Auction House.

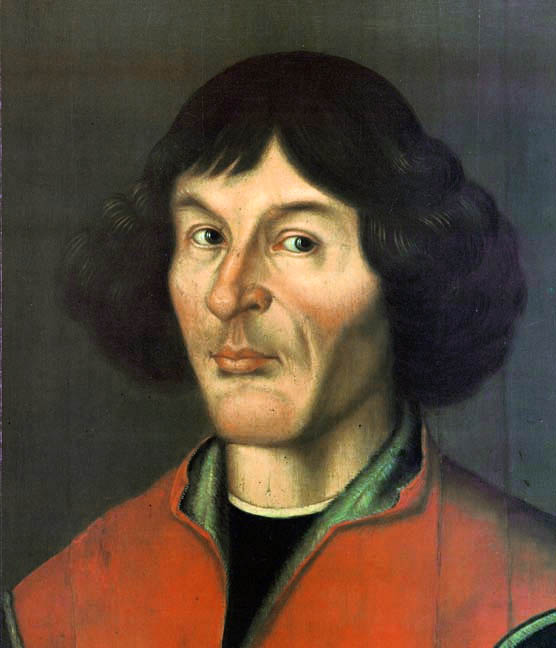

Of the 289 lots sold totaling $11,019,688 the most notable was De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri V, 1543 (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), the seminal work, by Nicolaus Copernicus, in which he explained his theory of heliocentricity.

The book, which is often referenced as the beginning of modern astronomy was sold for $2,210,500, the most expensive of the lot.

Galileo Galailei who furthered Copernicus’studies has three books that were sold among the top ten in price:

Operazioni del compasso geometrico, et militare, 1606; Sindereus nuncios magna, longeque admirabilia spectacula pandens; Difesa di Galileo Galilei … contro alle calunnie & imposture di Baldessar Capra, 1607.

Albert Einstein’s own collection of 130 offprints of scientific papers from 1900-1925, was also included in the top ten lot along with Charles Darwin’s Extracts from Letters addressed to Professor Henslow by C. Darwin, Esq., December 1, 1835 and can also be found online at Darwin Online.

Precious objects that tend to be sold at auctions obviously have a common allure. In singling out scientific items buyers seem to follow a certain trend. These works do not come up for action as often as priceless art or fine wine. However, they have their own allure to a specific niche of collectives, the eponymous Richard Green being a prime example.

Tobias Abeloff who is the senior book cataloger at Swann Auction Galleries in New York and has been there since 1982, has seen the industry go through many changes. What people buy, however, depends on a few components.

“Some people have an interest in professional and some have a peripheral interest in the items that they purchase,” he said.

Abeloff’s job of as senior cataloger requires him to prepare material in the book department for sales. Included are books from the science section. As with any subject desirability is the key factor.

“The history of science is pretty well documented so people know what works are available and that’s what they go after,” said Abeloff who is one of three catalogers at Swann Galleries. “With scientific books people have some sort of background which leads them to have an interest.”

As a witness to the changes associated with the antiquarian book market Abeloff says the internet is a huge influence. Despite the existence of online auctions like eBay, business in the world of traditional auctions remains lucrative. In some ways the internet has even helped broaden exposure, said Abeloff. He uses the example of Swann Galleries having more European ties and online-based exposure since the internet has come into play.

The next big emerging market in auctions, Abeloff assumes, will be items having to do with the history of computers. Though it may take a while, when and if buyers become aware of historical computer collectables Abeloff says it will affect prices.

There may be a benefit to those who have notable scientific items in their possession, which can be described as an appreciation of their scientific worth. Among the encouraging things that remain is that many of the collectors of these items are science lovers.

Those who have the appreciation but not the deep pockets need not shell out six figures for an original Copernican manuscript, however. The least expensive item from the Richard Green Library was The Applications of Physical Forces (1826-1893) by Amedee Guillemin, which sold for $63.

Comments