Stop eating your pet's food

Stop eating your pet's foodApparently people are eating their pet's food, and they're getting salmonella poisoning in return...

A scientific reference manual for US judges

A scientific reference manual for US judgesScience and our legal system intersect frequently and everywhere - climate, health care, intellectual...

Rainbow connection

Rainbow connectionOn the way to work this morning, I noticed people pointing out the train window and smiling. From...

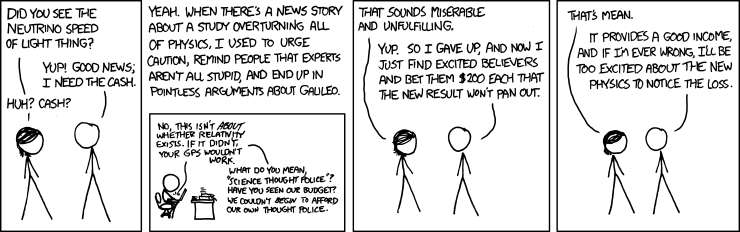

Neutrinos on espresso

Neutrinos on espressoMaybe they stopped by Starbucks for a little faster-than-the-speed-of-light pick me up....