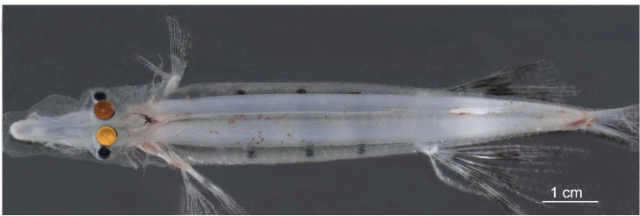

Spooooooky: The spookfish, as seen from above. The two eyes on the top have reflected the flash because of the mirrored surfaces present. Photo Credit: University of Bristol

Most vertebrates use a lens in the outer eye to focus light on to the back of the eye, where it creates a signal that is sent to the brain for processing. There are many different ways to do this, using one or more lenses (some vertebrates have multiple lenses that operate kind of like a telescope). By contrast, the spookfish uses a mirrored surface to reflect light on to a detector, instead of bending light through a lens. Although other organisms detect light this way, such as certain insects, the spookfish is the first vertebrate ever discovered with reflective eye surfaces.

Professor Julian Partridge from the University of Bristol, said: "In nearly 500 million years of vertebrate evolution, and many thousands of vertebrate species living and dead, this is the only one known to have solved the fundamental optical problem faced by all eyes – how to make an image – using a mirror."

The spookfish eye works something like a satellite dish - light enters the eye and is reflected off a concave surface toward a focal point. The mirrored surface focuses the light so that the intensity is increased, allowing for the detection of the very dim light found in the deep. Images detected by the retina that are cast in the reflected light are high-contrast and bright - perfectly adapted for ocean depths. Tiny plates, probably made of guanine crystals, provide the reflective surface. Guanine crystals are not unusual; they give fish that silvery color, but unlike most fish the direction and orientation of the crystals is tightly controlled so that the light is efficiently focused.

Biological Satellite Dish: Incoming light is reflected off of the mirrored surface in the spookfish eye and focused on the orange-colored detector, much in the way a satellite dish takes incoming light and focuses it to a horn. Photo Credit: University of Bristol

Spookfish eyes are also diverticular - meaning that the eyes are split into two connected parts. One part images upwards, looking for the food that will keep it alive. The other looks down and protects the fish's belly from predators that may be attacking from below. Both use the mirrored surface to reflect light and detect food or hazards.

First discovered 120 years ago, the spookfish itself is not new to science. Researchers did not know about the mirrored eyes, however, until Professor Hans-Joachim Wagner from Tuebingen University caught a living specimen off the coast of the island of Tonga in the southern Pacific.

We can only hope that continued exploration of the ocean depths will yield more exciting discoveries.

Comments