Based on a survey of UK science journalists and 52 in-depth interviews with specialist reporters and senior editors in the national news media, researchers from the Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies say that specialist science news reporting in the UK is in relatively good health, but also warn that a wider crisis in journalism poses a serious threat to the quality and independence of science reporting.

An international team of astronomers has viewed two distinct "tails" found on a long tail of gas that is believed to be forming stars where few stars have been formed before. The new observation was made by the Chandra X-ray Observatory and is detailed in a paper published this month in the Astrophysical Journal.

This gas tail was originally spotted by astronomers three years ago using a multitude of telescopes, including NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Southern Astrophysical Research telescope, a Chilean-based observatory in which MSU is one of the partners. The new observations show a second tail, and a fellow galaxy, ESO 137-002, that also has a tail of hot X-ray-emitting gas.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry have obtained 3-D images of the vesicles and filaments involved in communication between neurons. The effort was made possible a novel technique in electron microscopy, which cools cells so quickly that their biological structures can be frozen while fully active.

"We used electron cryotomography, a new technique in microscopy based on ultra-fast freezing of cells, in order to study and obtain three-dimensional images of synapsis, the cellular structure in which the communication between neurons takes place in the brains of mammals" Rubén Fernández-Busnadiego, lead author of the study, which appears in the Journal of Cell Biology

In a recently released report the National Research Council lays out several options NASA could pursue in order to detect more near-Earth objects (NEOs) – asteroids and comets that could pose a hazard if they cross Earth's orbit. While impacts by large NEOs are rare, a single impact could inflict extreme damage, raising the classic problem of how to confront a possibility that is both very rare and very important.

Far more likely are those impacts that cause only moderate damage and few fatalities. Conducting surveys for NEOs and detailed studies of ways to mitigate collisions is best viewed as a form of insurance, the report says. How much to spend on these insurance premiums is a decision that must be made by the nation's policymakers.

Research published in BMC Ecology suggests that genetics may provide valuable clues as to how to crack down on the animal smuggling trade, while also helping to safely reintroduce rescued apes into the wild. The population of chimpanzees across western Africa has decreased by 75% in the past 30 years, due in part to widespread chimp hunting, and new strategies are needed to curb this illegal activity.

Researchers have been comparing genetic sequences from rescued chimpanzees with those of their wild counterparts across several areas of the country and its border with Nigeria. In doing so, they hope to determine where the rescued chimps come from and thereby assess whether smuggling was a widespread problem, or if hunting hotspots existed.

How does an outfielder get to the right place at the right time to catch a fly ball? According to a recent article in the Journal of Vision, the "outfielder problem" represents the definitive question of visual-motor control. How does the brain use visual information to guide action?

To test three theories that might explain an outfielder's ability to catch a fly ball, researchers programmed Brown University's virtual reality lab, the VENLab, to produce realistic balls and simulate catches. The team then lobbed virtual fly balls to a dozen experienced ball players.

Opioid Addicts Are Less Likely To Use Legal Opioids At The End Of Their Lives

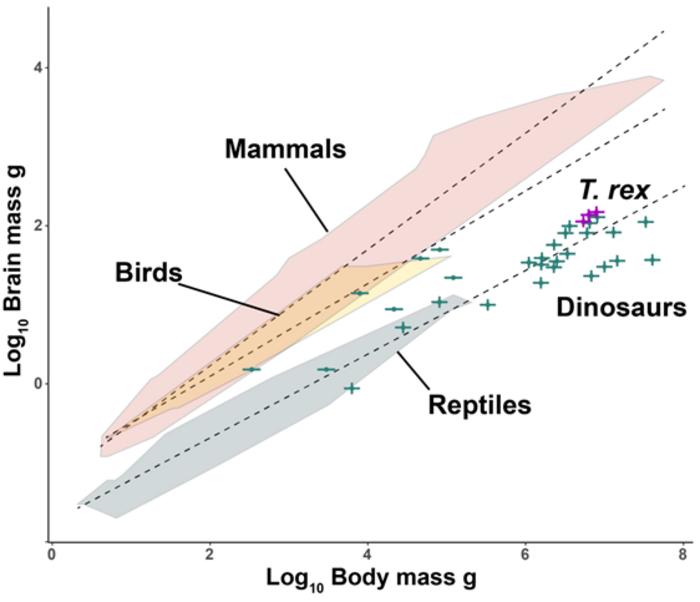

Opioid Addicts Are Less Likely To Use Legal Opioids At The End Of Their Lives More Like Lizards: Claim That T. Rex Was As Smart As Monkeys Refuted

More Like Lizards: Claim That T. Rex Was As Smart As Monkeys Refuted Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging Science Podcast Or Perish?

Science Podcast Or Perish?