Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And AgingIn mice, caloric restriction has been found to increase aging but obviously mice are not little...

Science Podcast Or Perish?

Science Podcast Or Perish?When we created the Science 2.0 movement, it quickly caught cultural fire. Blogging became the...

Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also

Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics AlsoTirzepatide facilitates weight loss in obese people with type 2 diabetes and therefore improves...

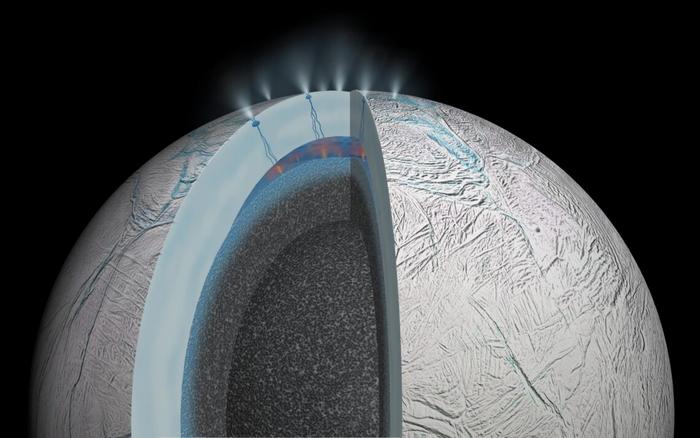

Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next Year

Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next YearLife may be detected in a single ice grain containing one bacterial cell or portions of a cell...