In the perpetual fight over evolution in public schools, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that supporters of science education have largely been successful in shutting down creationist attempts to undermine evolution through state legislatures and state school boards. While there is still mischief going on in many state legislatures, these efforts rarely go anywhere, thanks to vigilance by supporters of good science education. An essay in PLoS Biology today argues that, at the state level, things are going well:

At this time, not a single state uses its content standards to explicitly promote ID or creationism. School boards are monitored by organizations like the National Center for Science Education, by state academies of science, and by local scientific and professional organizations. As a result, few state school boards can formally consider measures like the one adopted in Dover without scrutiny and challenge from organizations representing the scientific profession.

But here comes the bad news:

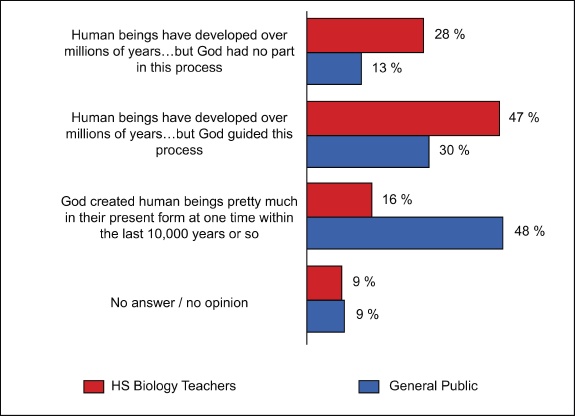

There are many reasons to believe that scientists are winning in the courts, but losing in the classroom.

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising?

Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising? Yep, This Should Get You Fired

Yep, This Should Get You Fired No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes

No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes