This drew a great deal of attention and organic advocate defense. Because even though Stanford is affectionately known by alums such as me as "the farm," it is certainly no ag-school promoting the status quo. Instead, it enjoys a very strong reputation for research excellence. It isn't easy to dismiss these findings.

Many commentators, confronted with the highly credible de-mythification of the nutritional advantage of organic, jumped to the paper's slight evidence supporting a 30% reduction in exposure to pesticide residues as a way to justify paying extra for organic. Does the science really support that claim? No.

What I found disappointing about the Stanford study was the weakness of its analysis of differences in pesticide residues. First of all, of the 9 papers it analyzed on this topic, only one was based on US crops. Seven were about European food and one was from Australia. The single US study used data from the 1990s. Since that time there have been significant declines in the usage of older, more toxic pesticides.

The Stanford-associated authors drew the cautious conclusion that "consumption of organic foods may reduce exposures to pesticide residues...", but they didn't do anything to put that statement in perspective. In fact, their analysis was only a comparison of the number of pesticide detections with no consideration of which pesticides were detected at at what levels. Without that information, one can easily be counting, as equivalent, chemical residues that could differ by a factor of a hundred thousand or million in terms of relative risk. The Stanford group may have been limited by doing meta-analysis instead of original research, but in any case this sort of "detection counting" is the same egregiously misleading "analysis" that is committed each year by the Environmental Working Group in compiling their "Dirty Dozen List."

How Would You Best Answer Questions About Pesticide Residue Safety

The truth is that at least for the US, there is a perfectly good way to answer the question, "Should we be concerned at all about pesticide residues on our conventional food?" There is a publically available, fully transparent, downloadable data-set that provides exactly the information needed to get those answers. Each year, a group in the US Department of Agriculture (USDA-AMS) conducts a huge effort called "The Pesticide Detection Program." (PDP). They collect thousands of samples of food commodities from commercial channels throughout the year, and then take them back to the lab and analyze each for hundreds of different pesticide residues. It is effectively a "report card" on the entire food production system about how well it protects consumers from undesirable pesticide exposure.

I've been working for a while to do a rigorous analysis of the latest available PDP data from 2010. It has been a daunting task, because it is a nearly 2 million row, 85MB document. It contains a great deal of useful information in a form not easily accessed or understood by the public. However; once this is data iscrunched; it is easy to see why the USDA, EPA, FDA conclude that consumers have no need to worry about the safety of their food supply from a pesticide residue point of view.

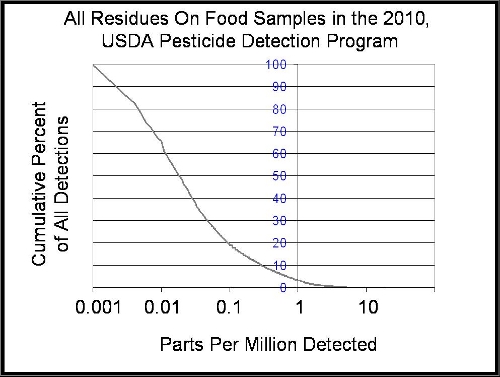

The graph above shows that the vast majority of the residues that the USDA scientists detect are at less than one part per million (1 milligram/kilogram). There really are not very many chemicals, synthetic or natural, that are of concern at these levels, but fortunately the USDA data does identify what the chemicals were and one can find out about them by searching for an MSDS (Material Safety Data Sheet).

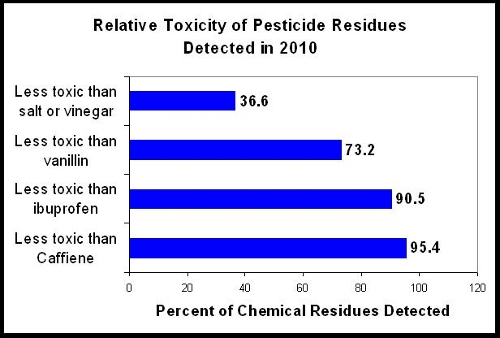

When most people hear the word, "pesticide" they imagine something quite dangerous. What they don't know is that over the last several decades, the old chemicals have been steadily replaced by much less hazardous ones that have emerged from a multi-billion dollar discover effort. That is why 36.6% of the residues detected in 2010 were for chemicals that are less toxic to mammals than things like salt, or vinegar or the citric acid in your lemons. 73 percent of the detections were for pesticides that are less toxic than the vanilla that is in your ice cream. 90.5 percent of the pesticides detected were less toxic gram per gram than the ibuprofen that is in the Advil tablets that tens of millions of people take on a regular basis. 95.4% of the detected residues were from chemicals that are less toxic than the caffeine that is in your coffee each morning. "Pesticide" does not equal "danger."

Even so, the best way to answer the question, "should I worry about pesticide residues?" is to compare what was detected to something called the "EPA tolerance." Companies that want to register new pesticides or to continue to use older ones spend well over $100 million dollars and several years of research to characterize the hazards (or lack thereof) that are associated with each chemical. These are used to inform a sophisticated, EPA-driven "Risk Assessment" process that determines if the chemical can be used and with which restrictions (e.g. how long the use must stop before the crop is harvested.) The "tolerance" that comes out of this process is designed to set a maximum level of that pesticide residue that should be detected in practice. This value includes a generous safety margin (on the order of 100x). Anything that is detected which is below the tolerance is not of any concern. The tolerances are set specifically by chemical with differences for each crop to reflect differences in the amount people would eat and which crops tend to be consumed the most by children.

What Does The Residue Testing Say?

The reason that the USDA can look at their data and make strong statements about safety is that the residues they find are virtually all below the tolerances, mostly far below (see graph above.) Only 7.8% of the residues detected in 2010 were even within the range of 0.1 to 1 times the tolerance. More than half were less than 1% of the tolerance (see graph above).

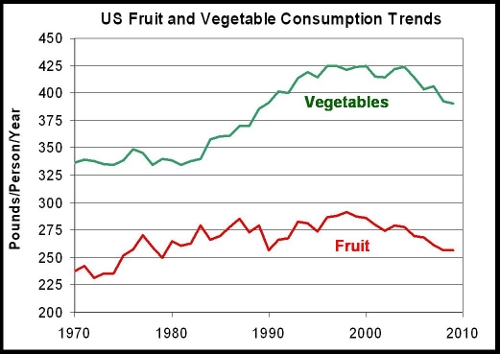

The Stanford study cited a 30% reduction pesticide residue detections which is essentially meaningless in the context of the miniscule risk associated. Unfortunately, many consumers have been convinced that there is a risk where there isn't one. They have gotten this from misleading promotion of organic as "pesticide-free" when it isn't, and by the scaremongering of groups like the EWG. The net effect of consumer concern about pesticide residues, driven by distorted messaging, is a reduction in fresh fruit and vegetables consumption (see graph above). After some modest increases in fruit and vegetable per capita consumption in the 80s and 90s, those trends have ceased or even been reversed. How much of that is related to disinformation about the risks associated with pesticide residues? It is hard to know.

This new study, even if it is from Stanford, does not provide consumers meaningful guidance on the question of whether they should spend more to avoid pesticide residues. The more relevant USDA data says that they don't need to hesitate to buy and consume "conventional" foods.

You are welcome to comment here or to email me at savage.sd@gmail.com. Graphs are based on USDA-AMS pesticide data and USDA-ERS produce trend data.

Comments