Not much. But it will still be a food frequency questionnaire epidemiology paper, the bane of public trust in science. What about confounders? Were people on medication, like statins? The people who had strokes were 59-60 when they enrolled in the survey, so what about their lifestyle choices prior to that?

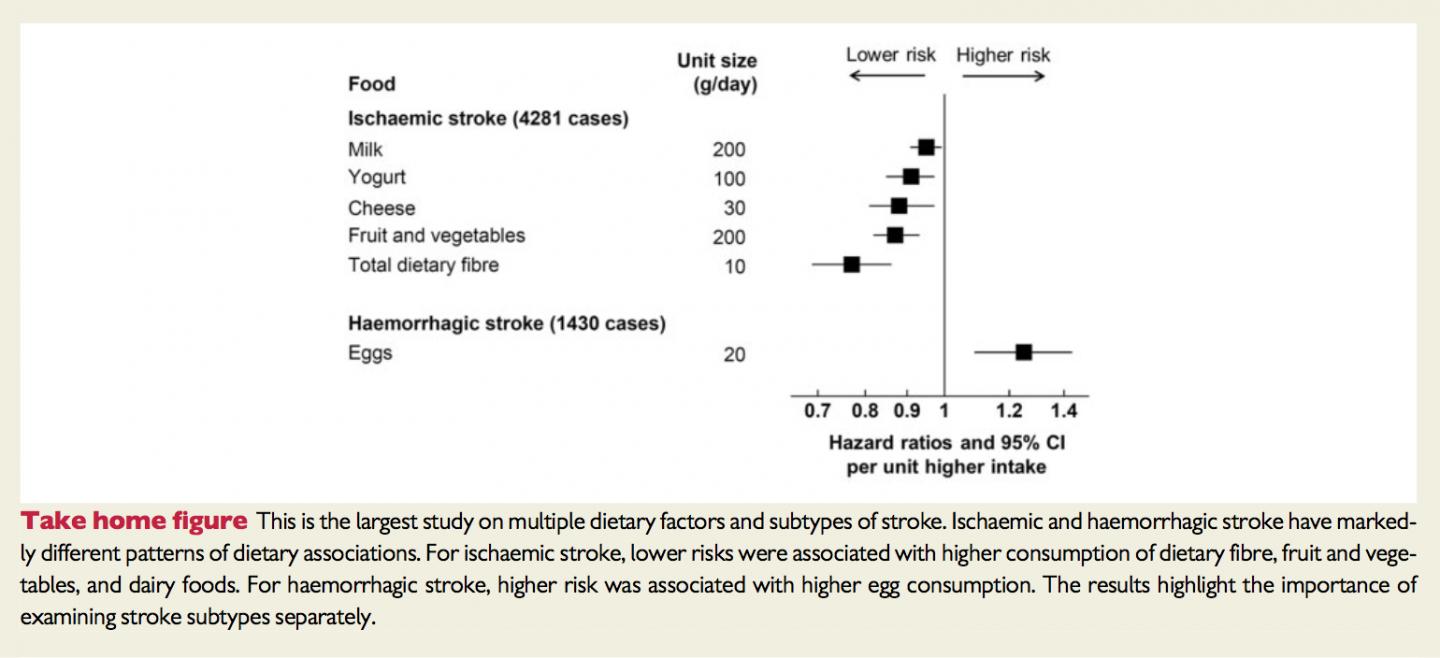

The epidemiologists have no idea, but they believe fruit, vegetables, and dairy products caused fewer ischemic (blood clot) strokes while eggs caused more hemorrhagic (brain bleeding) strokes. There were 4,281 cases of ischemic stroke and 1,430 cases of hemorrhagic stroke, out of 418,329 people in nine European countries in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Why did they use only nine countries - Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, UK - when EPIC is 10? Why did they leave out France? How did they calibrate the merged cohort problem when it is well known that EPIC mixes in recruited populations like blood donors with the general public?

We may never know so a more accurate synopsis would be 'Survey of Europeans leads scholars to claim various foods were eaten 13 years ago by people who later had two common types of stroke'. It's far less media friendly but more accurate.

In reality, the average follow up was 12.7 years but people were only asked to recall all of the foods they ate one time.

This may not be intentionally shoddy work, it may be earnest overestimation of validity but who makes a sweeping claim without at least a pretense of biochemical fact-checking to know if people eat what they say they eat? There is little point to a sample of 400,000 when it is a one-off diet survey, you are guaranteed to find something that 4,000 people have in common. It's hard enough to calibrate results if you know a lot, but they don't even know who had high risk factors because they don't know what medications people were on.

Food Frequency Questionnaires can be at least somewhat reliable, if you do it multiple times to get an idea how well people report - because they most often under-report. An obese person who ate a healthy diet the day before they took the survey is an obvious confounder. And when people are told to keep a diary they gamify that - it changes what they eat - or they forget a lot.

Without conceding all of that, this is media clickbait. Epidemiologists continue to perpetuate simplistic correlation long after experts realized food frequency questionnaires are sketchy because journalists love to write Miracle Diets and Scary Chemicals. Yet even Harvard School of Public Health, which has made FFQs linking every food to every outcome its fundraising mission, doesn't do something this simplistic now. It's the equivalent of using surveys of atomic bomb survivors and making it sound like that will be the general population.

Why do epidemiologists use them so much? For the same reason academic psychologists overwhelmingly survey psychology undergraduate students for their papers - it's cheap.

Of course, they always trot out 'we do not claim this is causal' verbiage when criticized for this, and specify that down at the bottom of the paper, but their press release reads "different foods linked to different types of stroke" and they know journalists and the public will see the word "linked" and believe that is causal, the way guns are "linked" to gunshot deaths.

Their press release image. Can you itemize how many things this intentionally does to confuse the public about what their results really mean?

If this was really intended to be exploratory, they wouldn't send out a press release to journalists. It would just appear in a journal the way 15,000 papers a month appear.

Cheap cost helps but sometimes you get what you pay for and that is why you shouldn't believe that eating a lot more fiber and less meat and the two fewer cases of stroke per 1,000 people over 10 years will be meaningful in your life. The authors have no idea what other factors were involved in people who did or didn't have a stroke. It is what physicists call statistical wobble no matter how strongly the epidemiologists claim their confidence interval is about a meaningless finding. It is useless for population intervention.

There are lots of good reasons to eat a healthy diet, but one thing that will matter is doing that from a young age. This paper has no idea what historical diet factors were in play, or much else, but at least they didn't have to pay $20 a person for the survey data to learn nothing.

Comments